Artificial Intelligence in the Modern World: Sub-Saharan African Perspective

Wesli Turner, MSc., Research Analyst, Leadership & Governance Policy Lab

wturner@africacfsp.org

Dr. John Bosco Nizeimana, Research Fellow, Leadership & Governance Policy Lab

bnizeimana@africacfsp.org

Introduction and Brief History

Countries are racing to revolutionize industries, and societies are utilizing smart technology, developed using artificial intelligence (AI), with the aim of creating a globally connected and attractive modern society. African nations are no exception. Critical to achieving academic and industrial competitiveness, African nations should invest in the development of digital infrastructure and training and education on AI. Simultaneously, African governments should develop policies and support initiatives focused on AI. This analysis contributes to the ongoing discussion on AI development in Africa which has received limited attention from researchers and scholars.

The term AI refers to computer models and branches that focus on creating smart machines that possess the ability to perform activities that require human intelligence. This in turn creates machines that demonstrate special intelligent skills similar to that of humans and animals in real-world situations. There are four characteristics that define the concept of AI according to Norvig and Russel, authors of the groundbreaking textbook Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (1995); thinking humanly, thinking rationally, acting humanly, and acting rationally.1Builtin, Artificial Intellligence, What is Artificial Intelligence? How Does it Work? (Builtin.com). https://builtin.com/artificial-intelligence (accessed January 24, 2021) These are key thinking practices that have historically defined the use of AI in the world today. When computer-based machines are deployed to ‘think’ and ‘act’ in the above-mentioned ways, then that resembles artificial intelligence in practice.

The first writing on AI and debates surrounding its multiple perspectives was published in the 1950s by Vannervar Bush and Alan Turing, leading experts in AI during World War II.2Chris Smith, Brian McGuire, Tine Huang and Gary Yang, The History of Artificial Intelligence, (University of Washington, 2006). https://courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/csep590/06au/projects/history-ai.pdf (accessed January 24, 2021) Their writings were specifically scientific in nature, debating whether machines could truly think and be able to perform tasks like human beings, such as playing chess, through rational thinking and behavior. Their work became the springboard to the current AI mindset prevailing in the world of technology today.

Current Global and Regional Frameworks on Artificial Intelligence

The rapid pace of technological and artificial intelligence innovation necessitates regulation and oversight at the global, regional, and state level. To date, there is no universal global framework on artificial intelligence, nor is there an internationally recognized definition of AI. Governments and inter-governmental organizations like the United Nations (UN) have created special committees, task forces and research centers to explore the implications of AI and robotics. The focus of these initiatives is to explore the implications of AI and robotics on crime, security, banking, and warfare. Today, less emphasis has been placed on defining the parameters of artificial intelligence, its implications for global development goals, or the ways to ensure data protection.3

In 2015, the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) established this Center for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in the Hague, Netherlands. The center is tasked with understanding the risk-benefit duality of AI and robotics from the perspective of crime and security within a single UN system. UNICRI, UNICRI Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, The Hague, The Netherlands, (UNICRI). http://unicri.it/in_focus/on/UNICRI_Centre_Artificial_Robotics (accessed January 24, 2021)4[1]Ricardo Vinuesa, Hossein Azizpour, Iolanda Leite, Madeline Balaam, Virginia Dignum, Sami Domisch, Anna Felländer, Simone Daniela Langhans, Max Tegmark and Francesco Fuso Nerini, The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, (Nature.com, 2020). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-14108-y (accessed January 24, 2021)

Current institutional and regional frameworks on artificial intelligence are limited. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) adopted a recommendation on AI policy in May, 2019 which, according to the recommendation, “aims to foster innovation and trust in AI by promoting the responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI while ensuring respect for human rights and democratic values.5OECD, Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence, (OECD Legal Instruments, OECD, 2019). https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0449#supportDocuments (accessed January 24, 2021) ” The recommendations also require states to adopt strategies and domestic polices geared towards the ethical implementation and development of AI. Adherence to the policy is confined to OECD member states and partner states. Currently, there is no African representation among the OECD members, though South Africa is a partner state. Despite non-membership, the OECD also works closely with African governments with the aim of meeting the two fundamental goals of the OECD: (1) a democratic society committed to rule of law and protection of human rights; and (2) an open, transparent, and free-market economy. In April of 2019, the European Commission of the European Union published ‘The Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence’.6European Commission, The Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (AI), (European Commission). https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/ai-alliance-consultation/guidelines (accessed January 24, 2021) The commission defines trustworthy AI as having three components: lawful, ethical, and robust. While this is an excellent start, the guidelines are nonbinding and framed within the context of European values which may or may not align with values in other areas of the world.

As of today, the EU is the only regional organization with biding laws and mechanisms which indirectly regulate AI through data protection laws. For instance, in October 2015, the European Court of Justice ruled that countries and companies must comply with European data-protection laws when transferring data outside of the European Union. Although, this does not directly regulate AI, it does however impact data transfers used in artificial intelligence.7Dirk Helbing and Evangelos Pournaras, Build digital democracy, (Nature.com, 2015). https://www.nature.com/news/polopoly_fs/1.18690!/menu/main/topColumns/topLeftColumn/pdf/527033a.pdf (accessed January 24, 2021)

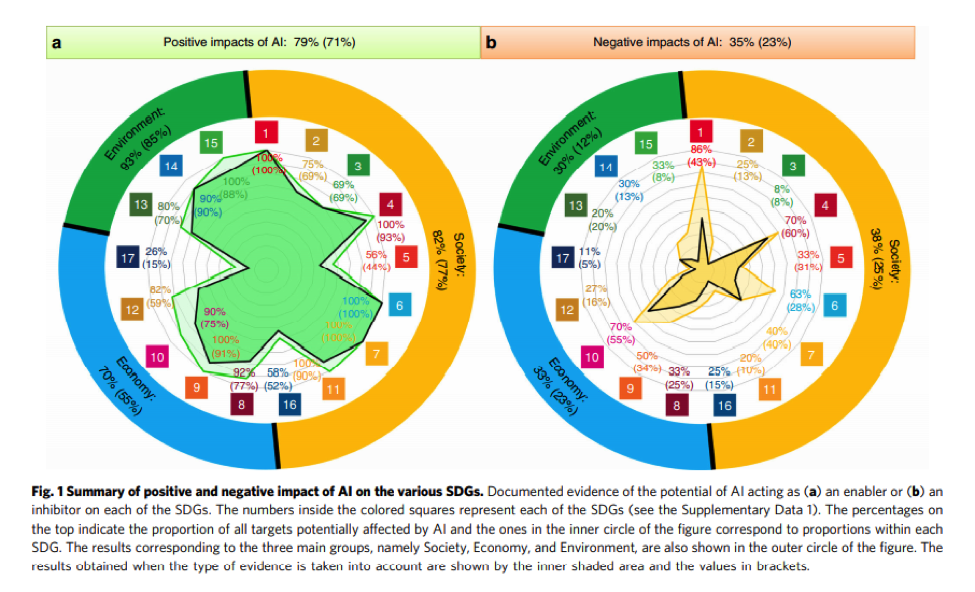

In addition to the above-mentioned policies and international recommendations and guidelines, the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute’s Center for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics conducts research on the implication of AI and robotics on crime, security, and warfare. This research drives international regulation on autonomous weapons and methods of using AI for criminal activity. There is limited attention paid to regulation of AI with regards to its use in development, education, agriculture, or other sectors. In 2020, Ricardo Vinuesa, Associate Professor at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, and colleagues highlighted the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) that could be impacted both positively and negatively by AI in a paper published by Nature Communications. The SDGs impacted were broken down into three categories – environment, economy, and society – and there was an overall 79% favorable impact on the UN SDGs with a possible 35% negative impact. The researchers concluded that there was a significant gap in regulation and oversight, which could have profound consequences on security, but more importantly on development and human rights.8Ricardo Vinuesa, Hossein Azizpour, Iolanda Leite, Madeline Balaam, Virginia Dignum, Sami Domisch, Anna Felländer, Simone Daniela Langhans, Max Tegmark and Francesco Fuso Nerini, The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, (Nature.com, 2020). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-14108-y (accessed January 24, 2021)

Artificial Intelligence in Sub-Saharan Africa

The existing mobile phone market and mobile technology solutions in Africa provide a baseline for an AI technological infrastructure.9Aleksandra Gadzala, Coming to Life: Artificial Intelligence in Africa, (Atlantic Council Africa Center, 2018). https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Coming-to-Life-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Africa.pdf (accessed January 24, 2021) For example, according to Pew Research, 80% of Kenyans and 71% of Nigerians own a mobile phone.10

Frankline Kibuacha, Mobile Growth and Penetration in Kenya, (Geopoll.com, 2021). https://www.geopoll.com/blog/mobile-penetration-kenya/#:~:text=A%20study%20conducted%20by%20Pew,50%25%20owning%20a%20basic%20phone. (accessed March 12, 2021); Ivan Forenbacher, Siniša Husnjak, Ivan Cvitić, Ivan Jovović, Determinants of mobile phone ownership in Nigeria, (Telecommunications Policy, 2019).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308596118303665 (accessed March 11, 2021) With the availability of mobile technology comes increased infrastructure for internet connectivity, and over 500 million Africans are connected to the internet; a lifeline for AI technology.11Internet World Stats, Internet Users Statistics for Africa, (Internetworldstats.com, 2021). https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats1.htm (accessed January 24, 2021) While there has been significant focus on Europe, Asia, and the Americas, major international organizations have argued that AI development in Africa is a top priority given its potential to improve education, health, ecology, and standards of living.12Forbes, Building A Community To Spread AI Across Africa, (Forbes.com, 2020). https://www.forbes.com/sites/insights-ibmai/2020/05/21/building-a-community-to-spread-ai-across-africa/?sh=31c17ca557a2 (accessed January 24, 2021) In fact, there has been a steady surge in African tech investments for start-ups since 2018, with the largest concentrations in South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya. However, this could plateau if Africa does not produce or maintain expertise and capacity for technological development. Experts from the Brookings Institute warn that if Africa fails to adapt to a technological future, it could be devastating for the continent, particularly for future generations. Africa boasts a large young population, with 60% under the age of 25. The failure to digitally innovate and match technological development with other countries around the globe could lead to large-scale unemployment or underemployment, with African countries unable to compete in a global market.13Fred Dews, Charts of the Week: Africa’s changing demographics, (Brookings.edu, 2019). https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brookings-now/2019/01/18/charts-of-the-week-africas-changing-demographics/ (accessed January 24, 2021) This could hamper sustainable development across Sub-Saharan Africa in the future, and future generations are likely to be compromised if no significant steps are taken to ameliorate the current situation.

Many African nations hope to use artificial intelligence to address development challenges, while others look to AI to increase productivity through automation. Tech giants have started piloting AI initiatives in some African nations. In Kenya, IBM’s “Project Lucy”, an extension of the supercomputer “Watson,” aims to address development challenges through collaborations with academies and partners using big data, while in Tanzania the creation of an app by Google assists farmers in diagnosing disease outbreak among cassava plants.14Aleksandra Gadzala, Coming to Life: Artificial Intelligence in Africa, (Atlantic Council Africa Center, 2018). https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Coming-to-Life-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Africa.pdf (accessed January 24, 2021); Alcober, Fred, AI takes root, helping farmers identify diseased plants, (Blog.Google, 2018). https://www.blog.google/technology/ai/ai-takes-root-helping-farmers-identity-diseased-plants/ (accessed January 24, 2021) However, a gap exists between capacity (trained data scientists) and a growing need for and interest in artificial intelligence in Africa. Acknowledging the need to have local experts to tackle local issues, African scientists such as Mustapha Cisse, a research scientist at Google and head of the Google AI center in Accra, Ghana, is working with academic institutions and corporate AI leaders to develop local and regional talent. His efforts are supported by technology companies with centers in Accra, Nairobi, and Lagos.15Moustaphe Cisse, Look to Africa to Advance Artificial Intelligence, (Nature, 2018). https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07104-7 (accessed April 19, 2021)

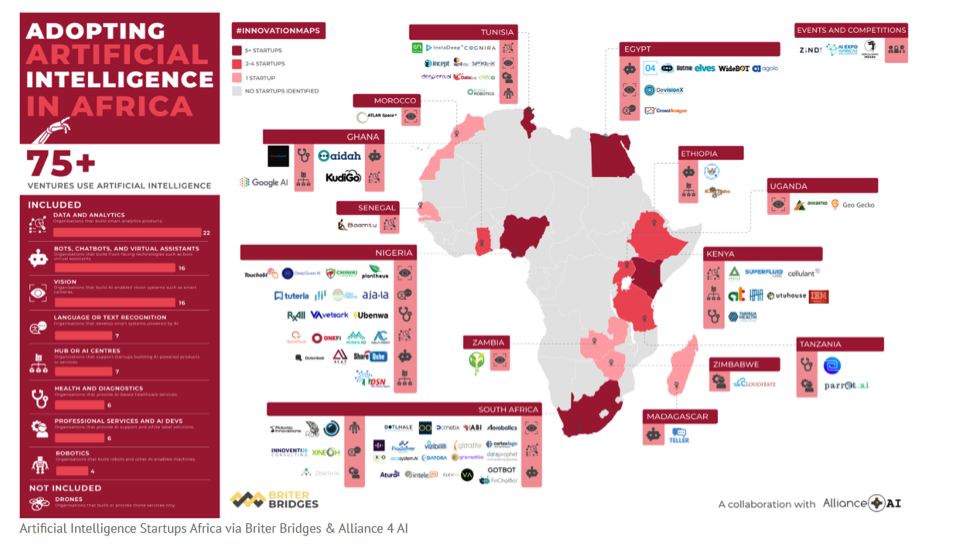

The adoption of AI in Africa is constrained not only because of capacity and investment but also due to state security. As shown above, of the 55 African nations, only 14 countries are represented in Briter Bridgers and Alliance map of ventures using AI. This is despite the positive implications AI can have on sustainable development goals such as education and food security.16AI Expo Africa, Artificial Intelligence in Africa – Will 2020 be a Tipping Point for African AI? (AIExpoAfrica.com, 2019). http://aiexpoafrica.com/2020/01/06/artificial-intelligence-africa-will-2020-tipping-point-african-ai/ (accessed January 24, 2021) Many of the countries not captured on the map are struggling with civil conflict, government failure, and lack of basic infrastructural development. Investment and development in AI could either help eliminate disparities among African countries or widen them, depending on the distribution of resources and technology.

Dr. Cisse is working alongside others to create the next generation of African AI scientists despite the obstacles. Sanctions, travel restrictions, and insecurity challenge the ability of some African scholars to travel abroad in order to keep up with their intellectual competitors and/or attract experts for local conferences.17Karen Hao, The future of AI research is in Africa, (MIT Technology Review, 2019). https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/06/21/134820/ai-africa-machine-learning-ibm-google/ (accessed January 24, 2021) Some obstacles have been diverted with the creation of local conferences, such as Deep Learning Indaba, held annually in Kenya and attracting some of tech’s biggest players, including American companies such as Google, Microsoft, and Apple among others.18Dave Gershgorn, Africa is Building an A.I. Industry That Doesn’t Look Like Silicon Valley, (One Zero, 2019). https://onezero.medium.com/africa-is-building-an-a-i-industry-that-doesnt-look-like-silicon-valley-72198eba706d (accessed January 24, 2021) However, there are deep divides among African states, between those which possess the infrastructure and security to attract investment and those which do not. Currently, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe have publicly announced AI projects, and in some cases, corporate research centers.16

While many African nations have started pursuing AI technologies, few have developed guidelines and frameworks to support government responses and investments. A notable exception is the government of Kenya. In 2019, Kenya’s Ministry of Information, Communication and Technology established an Artificial Intelligence Taskforce to “develop a roadmap for the transformative technologies of the fourth industrial revolution”.19Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology, Emerging Digital Technologies for Kenya: Exploration and Analysis, (Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology, 2019). https://www.ict.go.ke/blockchain.pdf (accessed January 22, 2021) According to the Future of Life Institute, which tracks AI policies around the globe, no African nation has established polices or taskforces dedicated to AI.20Future of Life Institute, Global AI Policy: How countries and organizations around the world are approaching the benefits and risks of AI, (Future of Life Institute). https://futureoflife.org/ai-policy/ (accessed January 23, 2021) This is particularly concerning considering the development of AI on the continent.

During the global coronavirus pandemic, African nations turned to AI to assist with COVID-19 testing and surveillance, proving its critical role in disease prevention and governance.21Christiaan Van der Merwe, AI deployed to fight Covid-19 in Africa, (ResearchProfessionalNews.com, 2020). https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-africa-partnerships-2020-12-ai-deployed-to-fight-covid-19-in-africa/ (accessed January 24, 2021) The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) joined forces with telecommunications companies, taking advantage of the mobile phone market in Africa to distribute advice on COVID-19 to over 600 million subscribers. The data gathered through The Africa Communications Intelligence Platform, a mobile phone platform launched in 23 African countries, was used to feed into COVID-19 health task forces to locate disease hotspots and help evaluate responses.22Bukola Adebayo, UN, telcos in Africa take on Covid-19 with AI and digital service, (CNN.com, 2020). https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/24/africa/un-africa-telcos-coronavius-intl/index.html (accessed January 24, 2021)

Concerns with AI

While the interest and demand for AI in Africa is growing among governments and African entrepreneurs, there is mounting concern over data protection, privacy, and the impact of AI on the job market. Predatory contracts between African nations and private industry take advantage of the lack of laws and policies on data protections and privacy, enabling companies to benefit from the collection of data on citizens without their knowledge or consent.23Chris Burt, Implementation of CloudWalk facial recognition technology in Zimbabwe progressing in stages, (BiometricUpdate.com, 2018). https://www.biometricupdate.com/201805/implementation-of-cloudwalk-facial-recognition-technology-in-zimbabwe-progressing-in-stages (accessed January 24, 2021) In some instances, foreign companies create masked subsidiaries disguised as African startups, taking advantage of the African market, but exporting its financial successes, leading some to claim that tech companies could pose as the new colonists of Africa.24David Pilling, Are tech companies Africa’s new colonists? (Financial Times, 2020). https://www.ft.com/content/4625d9b8-9c16-11e9-b8ce-8b459ed04726 (accessed January 19, 2021) This raises significant ethical concerns, and for this reason, among others, there needs to be policies in place to guide the development of the industry in a way that is ethical and humane, adopting the positive attributes of AI while limiting the negative effects.

Global Policy Recommendations

An internationally agreed upon definition of AI is needed as the foundation for a global framework to guide transparency, accountability, and the development of ethical standards. Binding standards for ethical designs are needed to ensure that states, institutions, and companies comply and limit negative impacts. Additional research is needed to gain further understanding of the implications of AI on all sectors, including human rights and privacy.

Support for non-government organizations (NGOs) and other non-profits such as the Future of Life Institute, which tracks policy developments on AI around the world, should receive resources to adequately monitor and report on developments, while additional resources should be dedicated to tracking and monitoring violations of global policies and frameworks. Funds should be allocated by governments as well as private industries. This is essential as it could promote policy formulations and analysis in the context of AI across different sectors of society.

Africa-Specific Policy Recommendations

African states should not forgo the adoption of AI based on its risks, but rather aim at striking a balance between regulation and innovation through the establishment of laws and policies on data protection and privacy to guide AI development and investors. Policies and frameworks should be developed with norms, structures, and processes that reflect the realities of operations in Africa.25Kinyunhu Ventures, Chasing Outliers: Why Context Matters for Early-State Investing in Africa, (Kinyungu.com, 2020). https://kinyungu.com/chasing-outliers/ (accessed January 24, 2021)

A first step for policymakers should be to ratify the African Union’s Convention on the Establishment of a Legal Framework for cyber-security and personal data protection. Currently, only 8 out of the 55 countries of the African Union have ratified the convention, preventing widespread adoption.26African Union, Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection, (African Union, 2020). https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/29560-sl-AFRICAN%20UNION%20CONVENTION%20ON%20CYBER%20SECURITY%20AND%20PERSONAL%20DATA%20PROTECTION.pdf (accessed January 24, 2021) The convention would aid in developing a blueprint that could guide investment and development of technology in Africa, while encouraging ethically built AI systems. Secondly, states should develop national frameworks to guide entrepreneurs and foreign investors, including frameworks around data collection and data sharing.

Thirdly, an African working group, as proposed by Egypt in December 2019, should be developed to create a unified strategy on Artificial Intelligence across the continent.27Al-Masry Al-Youm, Egypt Proposes Unified Strategy for Africa on AI Technology, (Egypt Independent, 2019). https://egyptindependent.com/egypt-proposes-unified-strategy-for-africa-on-ai-technology/ (accessed January 22, 2021) In addition, individual governments should establish taskforces, echoing efforts by the government of Kenya. These taskforces should evaluate existing AI technologies, future advancements, implications for the nation, and establish strategic areas where the government can support innovation. The taskforce should also acknowledge areas in need of support, such as additional investment in digital infrastructure.

To support African entrepreneurs and startups, governments should also create legal frameworks defining what constitutes an “African company”. This would aid in supporting genuine African start-ups and tech companies, while putting limits on foreign companies from misappropriating the terms to attract investments and then exporting the wealth. This would serve to protect African entrepreneurs as well as give guidance on foreign and domestic investment, creating a supportive ecosystem for AI startups and corporations.

While states focus on legislation and legal frameworks, non-profits and intergovernmental organizations should engage in campaigns to raise awareness of the positive and negative implications of AI with government officials, key stakeholders, and the general public, and invest in additional research and funding on AI projects.28Clayton Besaw and John Fritz, Artificial Intelligence in Africa is a Double-edged Sword, (Our World, 2019). https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/ai-in-africa-is-a-double-edged-sword (accessed January 24, 2021) Educated buy-in can serve both civilians and governments in adapting AI for local contexts and ensuring ethical practices.

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic of 2020 has demonstrated the need for governments to be connected and innovative. AI can play a central role in the development of solutions to global and local issues. The world is also increasingly faced with multiple challenges, ranging from cyber security threats, sophisticated terrorism campaigns, cross-border crimes, corruption, and climate change. Hence, legal frameworks, policies and guidelines are needed to ensure the ethical development and use of AI, laying the foundation for a smart, innovative, connected, and technologically savvy Africa of tomorrow.

Based on your interests, you may also wish to read:

- Imperial Reckoning: an exceptional investigation into the violence and brutality which characterized the end of empire in Kenya

- Neopatrimonialism and its Development in Africa

- Prosperity & Poverty in Post-Independent Africa Debated

- Overlapping Insecurities: Maritime and Agrarian Resource Management as Counterterrorism