Expanding Access to Quality Education: Rwanda’s pledge to women and girls

Amos Kulumba, Research Analyst, Youth, Gender, and Vulnerability Policy Lab

akulumba@africacfsp.org

Rebecca W. Ellison, Director, Youth, Gender, and Vulnerability Policy Lab

rwellison@africacfsp.org

In less than 30 years, Rwanda has made exceptional advances to redress social inequalities exacerbated by the devastating violence of the 1994 genocide. Advances in socio-economic and health outcomes have improved living standards for citizens and directed targeted funding ensuring universal primary education for most children. New conventions to mainstream gender equality have guaranteed an expanded female representation in politics and the workforce, enabling successive generations to contribute to the prosperity of Rwandan society. Though there are promising trends in the education sector, dangerous and competing patterns that perpetuate gender inequality also persist, threatening the success of these important advances.

Introduction

The 1994 Rwandan genocide disrupted services including schools, health services, businesses, local and national governance, and all aspects of community life for more than a year. Between 800,000 to 1,000,000 Rwandans were killed, of which 75% were Tutsis.1SURF Survivors Fund. 2022. Statistics. SURF Survivors Fund. Available: https://survivors-fund.org.uk/learn/statistics/ Additionally, approximately 3,000,000 people (about the population of Arkansas) were displaced either within Rwandan borders or throughout neighboring countries – disrupting communities and transforming the lives of millions of survivors impacted by deep physical, psychological, and sociological trauma.2SURF Survivors Fund. 2019. 35% of Genocide survivors have health problems. SURF Survivors Fund. Available: https://survivors-fund.org.uk/news/35-of-genocide-survivors-have-mental-health-problems/ Girls and women, the majority of whom were Tutsi, experienced gender-based violence (GBV), displacement, and impoverishment, as well as a lack of access to social protections. Between 250,000 and 500,000 women and girls were raped during the first 100 days of the genocide. Of all those who were tested for HIV/AIDS, 70% showed positive results for HIV/AIDS within five years.3Donovan, Paula. 2002. Rape and HIV/ AIDS in Rwanda. The Lancet. Available: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(02)11804-6/fulltext

Since 1994, political stability has improved living standards, impacting the health, economic, and education outcomes for most Rwandan citizens. Through consecutive Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategies, EDPRS (2008-12) and EDPRS-2 (2013-18), Rwanda’s annual capital growth GDP has averaged a seven percent increase annually. The strong economic growth enabled a significant decline in national poverty from 77% in 2001 to 55% in 2017.4The World Bank. 2022. The World Bank in Rwanda. The World Bank: Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/rwanda/overview#1 These improvements have enabled more women and their families to escape the crippling effects of multi-dimensional poverty.5Ibid.

However, in 2020, COVID-19 increased the headcount of those impoverished by five percent.[vi]Ibid.[/mfn] A decline in access to quality nutrition, health services, educational resources due to school closures, and sustainable income negatively impacts children from poorer households. Girls have also been disproportionally affected due to Rwanda’s gendered expectations. Cultural norms require girls to provide caregiving and other domestic responsibilities, preventing many from chronically poor homes from returning to school.

Closing Gender Gaps in Governance and Leadership

Since the genocide, Rwanda has emerged as a global leader in advancing gender equality. The country has achieved gender parity in parliamentary elections, with 61% of seats now occupied by female members of parliament.6The World Bank. 2022. The World Bank in Rwanda. The World Bank: Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/rwanda/overview#1 In 2021, it was even ranked by the Inter-Parliamentary Union as first in its achievement of parliamentary seats followed only by Cuba, the United Arab Emirates, Nicaragua, and New Zealand.7IPU Parline. 2021. Monthly ranking of women in national parliaments. IPU Parline. Available: https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=1&year=2021 It was also positioned first among African nations and ninth in the world in its progress towards narrowing the gender gap.8United Nations Rwanda. 2021. FAST TRACKING GENDER EQUALITY IN RWANDA: Comprehensive Legal Analysis of Gender Compliance under Rwandan Law. United Nations Rwanda. Available: https://rwanda.un.org/en/138522-fast-tracking-gender-equality-law-rwanda-comprehensive-legal-analysis-gender-compliance Strong political will to support gender equality is reflected in the ratification of regional and international conventions and protocols on gender equality and legislative policy reforms. Indeed, the nation is rapidly benefiting from public leadership and policy gains critical to advancing the prosperity of women and girls.

In 2000, Rwanda’s President, Paul Kagame, was given broad decree to ensure stability while also endorsing the rights of women who represented 70% of the population.9https://www.hrw.org/reports/1996/Rwanda.htm Rather than promote pro-women values grounded in a moral belief, he took a pragmatic and ethical approach, drawing upon a talented female workforce to rebuild the country. In a 2007 speech, he stated,

It is painfully evident that gender inequality constrains growth and poverty reduction. Frankly, Africa is missing out on productive potential of more than half its population. …The situation in Rwanda is not unlike other African countries. Rwandan society has similarly been characterized by unequal social, economic, and political relations between men and women. But, fortunately, things are changing. During our struggle for a better Rwanda, we firmly believed in equity, equality and opportunities according to the capabilities of all Rwandans, women and men.10Speech by Paul Kagame at the International Conference on “Gender, Nation Building and the Role of Parliaments” Kigali, 22/02/2007

Further, Kagame posted the following tweet on International Women’s Day 2020:

Whenever women gain, we all gain as a country. There can be no true progress without equality. Thank you for playing your rightful and equal role in Rwanda’s transformation. Happy International Women’s Day to our sisters, mothers & daughters in Rwanda and across the world.11https://www.migeprof.gov.rw/news-detail/whenever-women-gain-we-all-gain-as-a-country-president-kagame-on-the-international-womens-day-2020

In spite of his progressive views, his methods have attracted criticism. For example, Christopher Kayumba, a lecturer at the National University of Rwanda, concluded in 2014 that not only is women’s equality “…embedded within the RPF” but that “Kagame isn’t pushing for women just for the sake of it. He’s mostly interested in capable people.”12https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/140404-rwanda-genocide-parliament-kigali-rwandan-patriotic-front-world-women-education?loggedin=true The decrease in the male population after the genocide left many jobs traditionally held by men now open for women. According to researchers, a high volume of widows and single mothers arose to assume traditionally male roles, enabling them to develop new skills and competencies that were needed to rebuild the country. ‘Rwandaness’ replaced ethnic divisiveness among those left to rebuild the country as this process required new levels of cooperation and solidarity.

Through quotas established by the President, women continued to fill vacant parliamentary seats. During Rwanda’s first transitional parliament after the genocide, 10% of the 70 parliamentary positions were filled by women. With each successive year, this percentage grew. However, these sweeping changes did not emerge as a result of internal pressure or a rising consciousness among Rwandan citizens to reexamine gender relations between women and men. Instead, according to a study conducted by UNICEF in 2006, it was believed among many ministers that women, due to their capacity to be mothers, were inherently more capable to nurture and restore an ailing nation.13https://beautifulrwanda.org/2021/07/25/empowerment-without-equity-the-uncertain-progress-of-rwandas-female-peace-builders/

Perceptions of women’s leadership limited them to certain policy areas. Women primarily dealt with policy that either ‘softened male peers’ or advocated for the rights of women and children. It was rare that they manage policy which would result in a larger outcome of social and political consciousness about gender equality. Nonetheless, the appointment of women to cabinet positions did accelerate the passage of laws about inheritance, violence against children, and the 2008 law banning gender-based violence. These milestones were critical to the foundation needed for improved gender relations.

Today, violence is still embedded as an accepted belief system particularly within the realm of the home environment. Advocate Peace Ruzage – CEO of Aspire Rwanda, a Kigali-based NGO – argues, “the problem of violence against women in Rwanda, as with many African countries, is rooted in the cultural beliefs and notions of masculinity reinforced through generations.”14Mbaraga, Robert & Nakkazi, Ester. 2022. VAW in Rwanda. The United Nations. Available: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/vaw-rwanda Nadine Gatsinzi Umutoni, the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, states that elevated inequality constitutes a national security issue: “Ending violence against women and GBV is a national security priority and we have adopted a strategy and a policy of ‘zero tolerance’ to GBV across all sectors.”15Ibid. Policy reforms are as effective as the extent to which they can be monitored, and the education sector represents the most critical space to measure improvements to gender equality.

The Impact of Traditional Beliefs in Perpetuating Gender Norms

Traditional gender roles limit expectations for girls – discouraging many from continuing formal education and confining many to lives of domesticity, increased risk of early childhood marriage, child labor, and even human trafficking.16Bureau of International Labor Affairs. 2020. Child labor and Forced Labor Report. Bureau of International Labor Affairs. Available: https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/rwanda Boys, however, receive privileged attention and thereby outperform girls in 26 of Rwanda’s 30 districts.17Ibid. Those who complete schooling, often boys, benefit from improved access to formal employment, become successful breadwinners of their own households, and are ultimately skilled contributors to the economy.

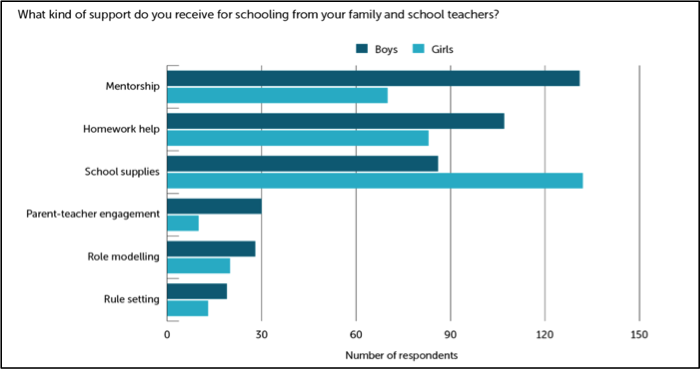

A study conducted by the Education Development Trust in 2021 of 140 girls and 140 boys in P4 and P5 across 10 districts revealed higher rates of school absenteeism among girls than boys primarily due to domestic responsibilities.18Cozzolino, Sofia; Munyaneza, Jean; Miller, Olivia; & Korin, Astrid. 2022. How evidence is informing the design of girls’ clubs in Rwanda. Education Development Trust. Available: https://www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/our-research-and-insights/commentary/how-evidence-is-informing-the-design-of-girls%E2%80%99-clu Boys reported spending more time with friends from school and, more importantly, devoting more time to study than girls. Teachers were less likely to provide mentoring and emotional support to girls to achieve good grades. In contrast, boys reported not only feeling mentored and getting homework help but benefiting more from parent-teacher engagement. Girls also felt less confident sharing their opinions amongst boys or men.

Figure 2: Support for Schooling

Source: Building Learning Foundations, Educational Development Trust (2021)19Ibid

In these early years, prevailing cultural and structural inequalities limit the success of even the best conceived educational policies designed to redress unequal achievement in the classroom. An example of this limitation is illustrated in a 2018 NPR story. In the story, Mireille Umutoni, a Rwandan teen, recalls feeling discouraged by teachers and fellow classmates to run for head of a school club. She asked, “Why can’t the head be a girl?” They responded, “That’s for Americans. You’re trying to be an American.” Mireille clarified that being “American” was shorthand for being too aggressive, too liberated, and too selfish. The message she took away was that her ambition was not good for her country. Mireille remembered their taunts: “You don’t belong in Rwanda. You don’t even belong in Africa!”20https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/01/10/577018509/rwanda-ranks-in-the-top-5-for-gender-equity-do-its-teen-girls-agree

Current and future generations of female students require much more support if they are to succeed as essential contributors to the advancement of Rwandan communities. Despite clear advocacy and laws protecting the rights of women and girls, especially from within the private sphere, continued progress is much more complex and difficult to assess. It is in these spaces that children receive foundational instruction about gendered norms through interactions with members of a household and the community. They learn about the roles, rights, and privileges enjoyed by male and female members of a household. They also are instructed on how to support, and even perpetuate, behaviors that may violate those very same laws designed to ensure the human rights of all citizens. It is clear that the home and the community are the important first spaces where concepts about gender roles and identity could reflect emerging aspirations from its youngest members.

Challenges to Formal Education in Rwanda

Rwanda is widely considered a top-performing African country in formal education with a 98% primary school enrollment rate, thereby meeting the Social Development Goals (SDG) of ensuring universal primary education.21Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. 2020. EDUCATION SECTOR STRATEGIC PLAN 2018/19 to 2023/24. Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. Available: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/education-sector-strategic-plan-2018-2024-rwanda The Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) provides free education for 12 years of schooling, with nine of these years considered mandatory. Comprehensive education policy reforms such as the Education Sector Strategic Plans, (ESSP 2018/19–2023/24) and (ESSP 2013/14–2017/18), were designed to strengthen the capacities of a future workforce, propelling Rwanda to achieve an industrial and upper-middle-income status by 2035.

According to MINEDUC, the anticipated impact of these policies will ensure that “Rwandan citizens have sufficient and appropriate skills, competencies, knowledge and attitudes to drive the continued social and economic transformation of the country and to be competitive in the global market.”22Ibid. Strengthening Rwanda’s education sector is essential in its transition to a knowledge-based economy with a workforce that can compete regionally and internationally. A capable labor force depends on the effective implementation of education policy guidelines; yet, consistent progress is questioned.

Indeed, despite policy guidelines that strengthen the education sector, challenges persist. Rwanda faces gaps in learning achievements, especially within urban/rural and private/government schools, dropouts, school repetition, and continuity of schooling. In 2019, the government of Rwanda mandated that English would be the official language of instruction for all primary schools. This decision represented the third change to the language of instruction in under eleven years, challenging teachers who primarily spoke Kinyarwanda or French to now provide instruction in English, of which only 38% had any working knowledge.23Ansoms, Ann; Cottyn, Ine; Niyonkuru, René; & Vrelust, Toon. 2021. The disappearance of half a million young people from Rwanda’s statistics. African Argument. Available: https://africanarguments.org/2021/01/the-disappearance-of-half-a-million-young-people-from-rwandas-stats/

For most students, education is also still not ‘free’ and, consequently, not accessible to everyone. Schools levy fees from parents to provide additional income for teachers and continued classroom construction and maintenance. Additionally, parents or caregivers are required to purchase school uniforms, books, food, and supplies for each child, further driving actual costs for education. According to UNICEF, only 71% of children in Rwanda complete primary school.24UNICEF. 2022. Education. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/rwanda/education Further, approximately 50% of students lack foundational knowledge, with profound disparities in numeracy and literacy among rural students and girls overall. Thus, these children have few marketable skills for the workforce. Many will be required by their families to support the informal economy as domestics and caregivers to children, the elderly, or disabled people at home. Alternatively, some will be encouraged to panhandle, cultivate agriculture, or engage in mining.

Figure 1: Learning Achievement in Rwandan Schools

Type of School | P2 Literacy | P2 Numeracy | P5 Literacy | P5 Numeracy |

All Schools | 45.3% | 32.9% | 44.1% | 38.3% |

All Urban Schools | 58.2% | 40.7% | 67.7% | 57.9% |

All Rural Schools | 43.7% | 31.9% | 40.9% | 35.6% |

Private Schools (urban) | 72.9% | 46.7% | 85.6% | 75.5% |

Government-aided (urban) | 50.7% | 37.9% | 56.4% | 46.7% |

Government-aided (rural) | 44.8% | 32.2% | 39.2% | 35.1% |

Public (rural) | 41.6% | 31.2% | 44.1% | 36.3% |

Source: MINEDUC (2018)25Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. 2020. EDUCATION SECTOR STRATEGIC PLAN 2018/19 to 2023/24. Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. Available: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/education-sector-strategic-plan-2018-2024-rwanda

Families endure variable losses in income due to school fees that impact children’s long-term success from poorer households. Even moderately poor homes may prefer to keep their children from attending school rather than hiring external labor for family farms or businesses, consequently raising the opportunity costs for education. Parents or caregivers may prioritize boys’ education over girls’ due to gendered cultural beliefs among educators that boys, in general, are inherently more intelligent and achieve higher academic scores than girls. Facing gendered expectations in the classroom, a lack of supportive advice from educators, and few role models, the participation from girls in schooling becomes discouraged, especially in the higher primary grades and secondary education.

A Crisis of Inefficient Spending

Research shows that when girls and women benefit from more targeted educational financing, every indicator of living standards from health to economic thriving increases.26Roser, Max & Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban. 2016. Financing Education. Our World in Data. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/financing-education Government spending as a total of the GDP for education is three percent, a statistic below the average for the continent which is five percent.27Gandhi, Dhruv. 2020. Figures of the week: Public spending on education in Africa. Brookings. Available: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/02/13/figures-of-the-week-public-spending-on-education-in-africa/ While the government has made the improvement of education a national priority, its budget allocation for spending has focused more on improvements to integrating Information, Communication, and Technology (ICT) into classrooms rather than on teacher training.

Notable achievements have been made with universal enrollments at the primary school level. However, a wide gap remains in gender parity in the completion of 12 years of schooling for girls and boys. In 2018, on average, a poor girl from a rural background only received four years of schooling compared to nine years for boys.28The University of Cambridge. 2022. Research Centers. The University of Cambridge. Available: https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/centres

In 2018, the World Bank launched a study that included an indicator for Learning Adjusted Years of Schooling and assessed years of school attendance and whether children are learning. As stated, on average, girls in Rwanda achieve only four years of learning.29Filmer, Deon; Rogers, Halsey; Angrist, Noam; & Sabarwal, Shwetlena. 2018. Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling: Defining A New Macro Measure of Education. World Bank Group. Available: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30464 However, the number of years can be even less when considering a family’s degree of impoverishment and other inequalities such as the inability to pay multiple school fees for all children within a family, long distances to travel to school, and the need for additional care for younger or older members of a family that girls are pressured to endure.

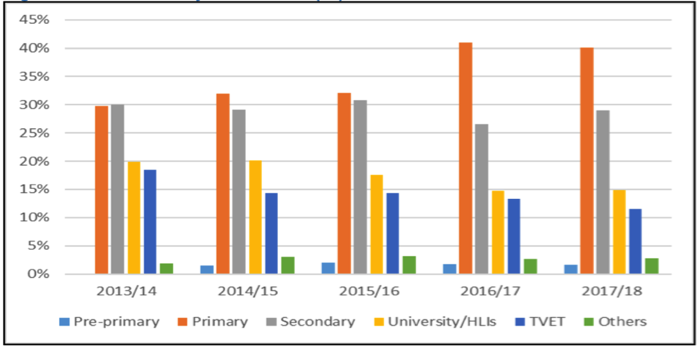

While the government allocates more funding for primary schools in absolute value, it also prioritizes educational improvements for secondary and tertiary schooling rather than for primary education. The costs of attending secondary and tertiary education are, hence, higher than primary education and escalating costs are often the result of inefficient allocation and spending. Increased funding for secondary education is also justified by the fact that fewer students transition from primary to secondary school due to lower pass rates of standardized testing requirements or an inability of parents to provide funding for school fees. It is estimated that universal access to secondary education is not achievable if secondary education costs exceed cost ratios to primary education by three to one. The Rwandan government spends seven times more on secondary education than it does on primary education.30Ibid.

Figure 3: Education Spending

Source: MINEDUC (2018)31Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. 2020. EDUCATION SECTOR STRATEGIC PLAN 2018/19 to 2023/24. Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. Available: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/education-sector-strategic-plan-2018-2024-rwanda

Integrating Gender Sensitive Policies Within National Strategic Plans

As mentioned earlier, Rwanda has made rapid progress in integrating gender-competent protocols in government strategies. It is a signatory to several gender equality conventions, declarations, policies, and programs. Relevant initiatives include the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and the Convention Against Discrimination in Education.

Several of Rwanda’s national policies and strategic plans integrate gender responsive awareness into policy initiatives. The Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS 2) and the Education Sector Policy and the Education Sector Strategic Plan (ESSP) integrate a strategic vision and approaches that address specific areas for improvement for the capacity development and participation of women. The 2021 National Gender Policy, the Girl’s Education Policy (2008), and the Girls’ Education Strategic Plan (2009-2013) aim to strengthen girls’ participation and achievement in all levels of education.32Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. 2008. GIRLS’ EDUCATION POLICY. Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Education. Available: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/94008/110190/F-1833244927/RWA94008.pdf Some efforts that align with these strategies are having a positive impact. Yet, COVID-19 has caused disruptions to many programs and has possibly caused a reversal in progress.

The Learn! Project USAID/Rwanda

In 2021, a desk review was conducted by the USAID/Rwanda Office which examined how cross-cutting issues of gender, disabilities, and social inclusion impacted experiences of learning through its Learn! Project (2015-2020) within the Rwandan basic education sector.33https://www.usaid.gov/documents/learn-project-gender-equality-and-social-intrusion-analysis The evaluation of the program was designed to include primary field research and data collection as well as desk research that would inform the design and implementation of a new Learn! Project (2020-2025). The Rwandan government’s decision to close schools during the pandemic limited the ability to collect and integrate primary data for the desk review. However, once this evaluation has been completed, the USAID/Rwanda Office will use these outcomes to provide recommendations on how to improve understanding and learning around gender and social inclusion.

The Learn! Project included key activities to support children with disabilities as well as a comprehensive strategy on learning outcomes for girls and boys, a gender sensitive pedagogy, books and curricula written with a gender sensitive lens, and teacher training. Some initial findings from the desk research revealed certain barriers within the classroom are still observable in spite of USAID/Rwanda’s investment to shift these trajectories:

- Girls are more likely to complete primary school than boys by the expected age 12. They are also less likely to repeat grades or drop out. However, this trend reverses when they reach secondary school with more girls dropping out than boys due to social expectations and gender bias about the value in educating boys over girls;

- Socio-cultural norms that prevent full participation from girls persist (e.g., remaining silent or providing more consultative space for boys to speak);

- Teachers lack training in using gender responsive pedagogy in the classroom; and

- Girls are less likely to find female role-models among those serving in high-level and decision-making positions, a reality which reinforces beliefs about the need for women to be invisible in school administration.

Legal frameworks, policy guidelines, and full participation from female leadership in all aspects of governance are critical for success in improving gender relations as they reflect the aspirations of citizens vested in a promising future for the next generation. Programs like the Learn! Project should be continually refined in order to strengthen learning outcomes for all children. Achieving gender-related commitments, however, will require persistent focus from not just the government but all segments of civil society, educational institutions, faith communities, and households.

Policy Recommendations

The following recommendations complement existing gender-responsive strategies:

- Close gender data gaps and improve data monitoring. There are critical challenges in collecting data on gender indicators which are used to track SDG goals. In 2020, according to UN Women, only 39% of data was available with gaps in areas such as unpaid labor/care, domestic work, and ICT skills.34UN Women. 2022. Rwanda. UN Women. Available: https://data.unwomen.org/country/rwanda In addition, methods for monitoring cross sectional issues such as gender and poverty, physical and sexual harassment, women’s access to assets, and gender and the environment lacked complementarity, leading to challenges in data integrity;

- Call upon national and local parliamentarians to address progress and remaining challenges to improve the experience of basic education in Rwanda. The nation has made enormous progress in just a few decades and development cannot be stymied by an unwillingness to examine socio-cultural values that limit the education and progress of half the population;

- Continue to provide teacher training using Gender Responsive Pedagogy.35FAWE Rwanda Chapter. 2022. Gender Responsive Pedagogy. FAWE Rwanda Chapter. Available: https://www.fawerwa.org/spip.php?page=program&id_article=16 Ongoing pre-service and in-service teacher training could integrate methods that specifically focus on reshaping attitudes and beliefs about the roles and capacities of women and girls. This would include the continued evaluation of textbooks and teaching tools written to include gender messaging;

- Engage local stakeholders, community leadership, faith centers, and households in forums that address the equality of women and men within the home and community. Community spaces, such as those described as Umuganda, where members meet monthly could be used as forums for those with concerns about gender inequality specifically in the school systems. These spaces, which are likely accessible to students and those unschooled, could be used to advocate for issues and devise solutions that directly impact their experiences;

- Use radio, print, television, and social media using storytelling to promote gender-positive messaging as part of national and local communication campaigns;

- Engage men and boys through community-based programs to examine inherited beliefs and cultural norms that impact girls’ full participation in school settings, professional environments, and community life. School leadership positions tend to be filled by men (87%), making it essential to include them in these community efforts36Cozzolino, Sofia; Munyaneza, Jean; Miller, Olivia; & Korin, Astrid. 2022. How evidence is informing the design of girls’ clubs in Rwanda. Education Development Trust. Available: https://www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/our-research-and-insights/commentary/how-evidence-is-informing-the-design-of-girls%E2%80%99-clu;

- Provide support to clubs for girls that are safe spaces where girls can advance self-esteem, develop academic excellence, and aspire career goals.

Through resilience, Rwandan citizens overcame enormous odds to answer the call of their leadership to rebuild their nation. Through numerous policies, laws, and strategic plans, citizens are again being called to show vigilance in protecting the rights of girls and women whose vital contributions are frequently devalued and silenced while still in school. Their ability to benefit from at least 12 years of quality formal education will be essential for improved learning outcomes for future generations. Education is a human right and mothers are also the first educators of children. It is the obligation of Rwanda’s leadership to demonstrate diligence in promoting the interests of the family and to become true champions of girls’ education. The delay in guaranteeing this essential right and responsibility will certainly hinder enduring prosperity for the nation.

Based on your interests, you may also wish to read:

- Women as Peacemakers in Senegal – Voices To Be Heard

- Imperial Reckoning: an exceptional investigation into the violence and brutality which characterized the end of empire in Kenya

- Burkinabe Men in Collective Action Against Gender-Based Violence

- Overlapping Insecurities: Maritime and Agrarian Resource Management as Counterterrorism