Five Questions to Consider in a Cameroon-Anglophone Swiss-Led Peace Talks

Jean Claude Abeck, President and Chief Executive Officer, Africa Center for Strategic Progress

jcabeck@africacfsp.org

Negotiating a genuinely democratic resolution of the crisis between Cameroonian authorities and Anglophone (former British administered Southern Cameroon) separatist groups will require a broad-based, just, and inclusive dialogue—one that addresses historical and constitutional grievances while reaching out to all stakeholders.

Anglophone protesters on the streets of Bamenda, Cameroon. (Source: Journal du Cameroun)

Working closely with the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs in Switzerland has committed to negotiating a solution to the crisis in the English speaking regions of Cameroon, where anglophones have launched an armed separatist campaign from the French-speaking majority. In preparation, I ask, what are the primary challenges to consider during negotiations? I present five pressing concerns to examine as talks develop:

The roots of the crisis are historical, constitutional & complex. To what extent will the parties appreciate the dynamics of the conflict?

At the core of the conflict lays deeply-rooted historical and constitutional grievances. The dynamics of the current crisis began as an extension of the resistance towards the erosion of Anglophone culture in Cameroon. In October 2016, the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium (CACSC) peacefully demanded a return to a two-state system of government and the preservation of the legal and education systems of Anglophone Cameroon.

Historically, in February 1961, after attaining independence, British-administered Southern Cameroon voted to join French-administered Cameroon (also referred as Francophone Cameroon) through a United Nations-supervised plebiscite. Four months later, the Foumban Constitutional Conference birthed the two-state federation. The conference is known as the marriage between British and French Cameroon. Just like when London and Beijing promised Hong Kong the “one country, two systems” model in 1984, so too did the Foumban Conference promise the Anglophones one country with two equal systems. However, recently, thousands in Hong Kong resorted to violent protest, a move to protect what they consider China’s encroachment on their sovereignty.

Map of Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis

Source: International Crisis Group

Constitutionally, in 1972, former President Ahidjo altered the structure of the union by abandoning federalism and transforming the country into a unitary state known as the United Republic of Cameroon. Later, in 1984, President Paul Biya changed the name to the Republic of Cameroon, the original name of French-administered Cameroon. To some elite Anglophones, changing the name was an act of secession from the union. It systematically eroded bicultural features of the country and violated the one-country-two-system promise. Despite several attempts by sections of the Anglophone population to resist what they considered as the erosion of their identity, French Cameroon continues to dominate their English counterpart, leading to what has now termed the marginalization of the Anglophones.

The form of the state: beyond grievances or more of the same?

Scholars typically agree that grievances alone do not necessarily lead to war. In the case of Cameroon, overwhelming evidence suggests that the Cameroon government has consistently neglected and disrespected constitutional safeguards of the peaceful coexistence of two distinct peoples. Since taking office in 1984, President Biya has ignored calls to redress legitimate grievances. One prominent call is the special tribunal of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights that Anglophone Cameroonians are a distinct people, recommended constructive dialogue between both parties. Ignoring this declaration was in part a failure to recognize a legitimate and separate Anglophone Cameroon as promised during the Foumban Conference. As such, any meaningful negotiations should begin by addressing the historical and constitutional foundations of Cameroon.

Moreover, to consider the Anglophone crisis as a mere grievance is a disservice to historical facts. Any dialogue or negotiation must refrain from conflating the marginalization experienced by Anglophones with other problems in the country. Equating the Anglophone problem to other grievances across regional lines in the country has been a point of contention between Anglophone and Francophone Bishops in Cameroon. Anglophone Bishops argue that the Anglophone problem is beyond grievances and more of an annexationist disposition. As such, any attempt to exclude the structure of the country from the peace talks is unrealistic, given this background, and is bound to fail. Both parties should be encouraged to open up to concessions and be willing to dialogue without preconditions.

Would the Biya regime show some Political Will to end the crisis through dialogue?

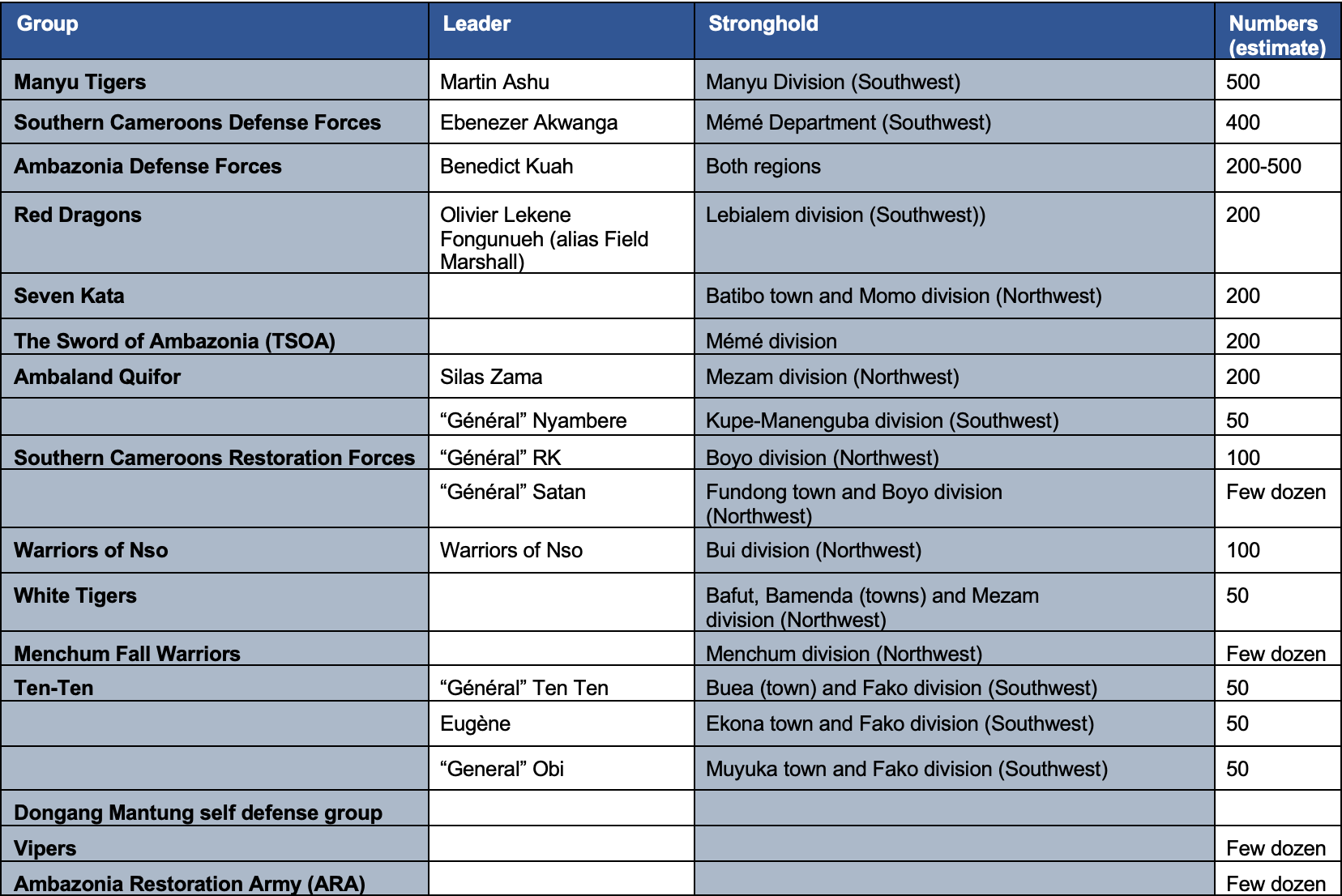

President Paul Biya’s declaration of war against separatists two years ago is indicative of a choice to repress peaceful protest. The initial response from Cameroonians in the two English regions was civil disobedience that ultimately spiraled out of control, with over 20 armed groups now fighting government forces. Armed resistance is being led by young separatist hardliners who are yearning for change and a better future after 36 years under Biya’s rule. Given a history of negligence from a Francophone-dominated government, most separatists do not believe change will come from continued integration with French Cameroon. Biya’s approach is the result of a miscalculation that the current rebellion is primarily against his longtime rule. Rebels, for the most part, want to see a real change to the political system.

Whether President Biya’s stance towards war will shift with the promise of negotiation is yet to be seen. However, with continued hostilities on both sides, it will be hard to convince rebels that the government will commit to negotiating with the separatists they once termed terrorists.

Since the start of the conflict, Cameroon’s prison population has increased. Although the actual figures are unavailable, this increase is projected from a steady rise in Cameroon’s prison trends from 2000 to 2015. Similar lessons from other countries underscore the importance of releasing political prisoners as a gesture of good faith towards dialogue. The first step to convincing parties would be to release all political prisoners unconditionally. Although the Cameroon government has made some concessions since 2017, analysts claim they were disingenuous, ill-conceived and resulting from international pressure. To boost trust and confidence in the process, the Swiss government should also consider a legally binding framework for talks. That could mean seeking the legal offices of the United Nations and the African Union, among other external actors.

What role will historical and external actors play?

Cameroon is a strategic partner for many western countries, especially given its historical position as a stable oasis in central Africa; thus, many external actors may have an interest in ignoring the government’s hardline. For many years, Cameroon has been a critical partner in the fight against Boko Haram. A spillover of violence in Anglophone Cameroon may jeopardize efforts towards containing the threat. Potentially, it could destabilize other former French colonies, affecting France’s interest in the region. Some religious authorities in Cameroon have accused France of aiding a government crackdown on separatists and promoting a Francophone-dominated government.

Also, China’s policy of non-intervention is in the government’s favor. Complicating these further is that neighboring Nigeria faces separatist groups of their own. Any actions on her part may be validating the Biafra secessionists. Understandably, this might cause external actors to hesitate in recognizing separatists calls for an Anglophone state.

Besides Switzerland, the United States has called for sincere dialogue between authorities and the rebels. So far, the US appears to be the most outspoken against the government. For instance, as recently as July 1, a US congressional delegation visited the country; and called for talks between the government and rebels. US participation in the peace talks is likely to boost confidence on the side of the rebels, giving a real chance for peace talks. The US has the means to enforce an agreement given its foreign policy resources. First, they could levy additional conditions on security assistance and impose sanctions on individuals found guilty of human rights abuses.

How will the different actors align with a peace deal?

Consulting all sides within the Anglophone community is ideal, but is it feasible given the current factions?— Federalists, separatists, regionalist (decentralization) and a divided civil society & Francophone opposition are all fighting to be heard. The latest report from the International Crisis Group on Cameroon identifies how public opinion of Anglophone Cameroonians has shifted over the years. In December 2016, CACSC demanded a return to the two-state federation. Today, a significant portion of Anglophone Cameroonians support federalism. But those who advocate for a separation of the two Cameroons argue that the Francophone state machinery is profoundly undemocratic and beyond reform, and therefore, the best way out is to restore the Anglophone identity through independence.

Also, separatism (and the emergence of armed militias) gained traction at the end of 2017 due to the government’s intransigence. The separatists are those that advocate for a complete breakaway of the” Union” formed in 1961 and call for an independent Anglophone Cameroon. Most separatist groups are organized around the supposed Interim Government of all Anglophones, and the Ambazonia Governing Council, who both claim to be the legitimate government for Anglophones. The report has identified upwards of 20 armed groups consisting of militants who pay allegiance to diaspora leaders with varying approaches to the armed resistance.

Some groups from the civil society, including Francophone political groups, have expressed regionalist positions but have failed to galvanize significant support from citizens at large. Regionalists, for the most part, espouse the desire to see a decentralized system of governance with more regional autonomy coming from the center. While the current constitution calls for a decentralized system, the government has never fully implemented it. Some Francophone-dominated political parties like the Cameroon Renaissance Movement, the Now Movement, and the Cameroon People’s Party have expressed their support for decentralization. The challenge ahead of peace talks would be to agree on the most suitable path forward.

Armed Separatists Presence in the Anglophone Regions: Data from the International Crisis Group

“Cameroon’s Anglophones Crisis” (2019). Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis: How to Get to Talks? International Crisis Group, Africa Report N°272, 1-44. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/cameroon/272-crise-anglophone-au-cameroun-comment-arriver-aux-pourparlers

Collier, Paul, and Hoeffler, Anke. (2000). Greed and Grievance in Civil War. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2355. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=630727

Okereke, C. (2018). Analyzing Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, 10(3), 8-12. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26380430

No related posts.