How Can Sub-Saharan African Countries Minimize the Impact of Coronavirus Pandemic on Economic Performance?

Dr. Oulatta, Expert Consultant, African Political Economy, USA

moulatta@africacfsp.org

I. Introduction

The large-scale effect of coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) sparked world-wide concerns over global economic developments. For Sub-Saharan Africa, the pandemic’s spillover effect on global trade and commodity prices has rendered its economic outlook bluntly uncertain. Particularly, because of the fact that the region’s economic trajectory remains on a balance-of-payments-constrained growth path. Which implies that Sub-Saharan Africa’s growth depends strongly on export, but the ability to import is also constrained by financial inflows and strong export performance; which in turn predictably depends on stronger commodity prices, foreign demand, and competitive depreciations (at least in the short run).

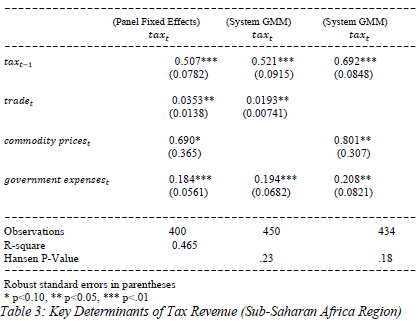

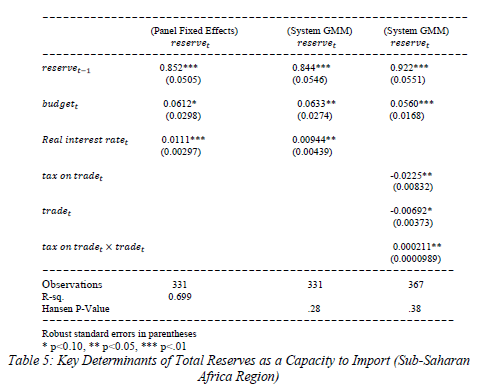

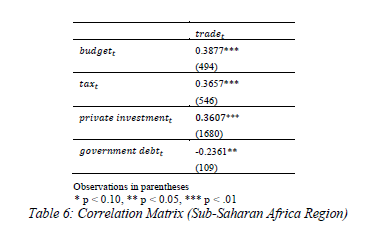

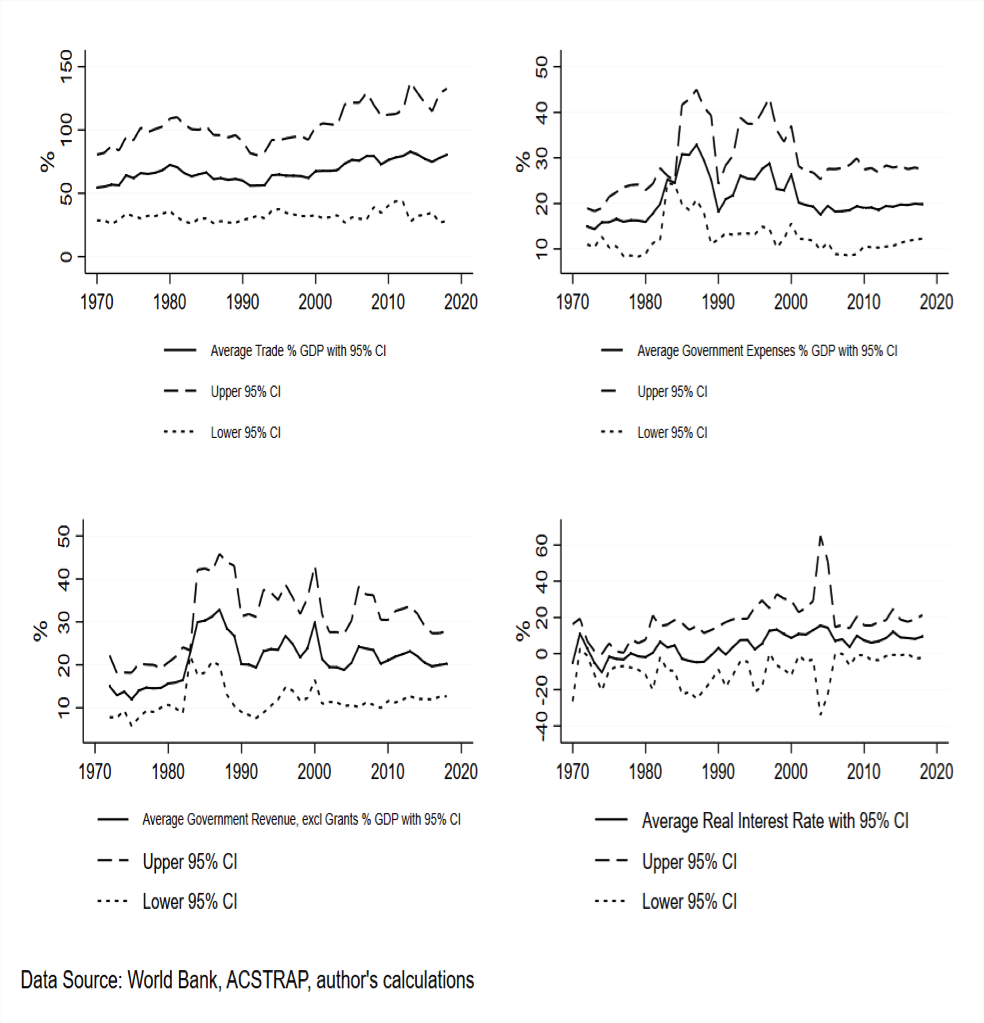

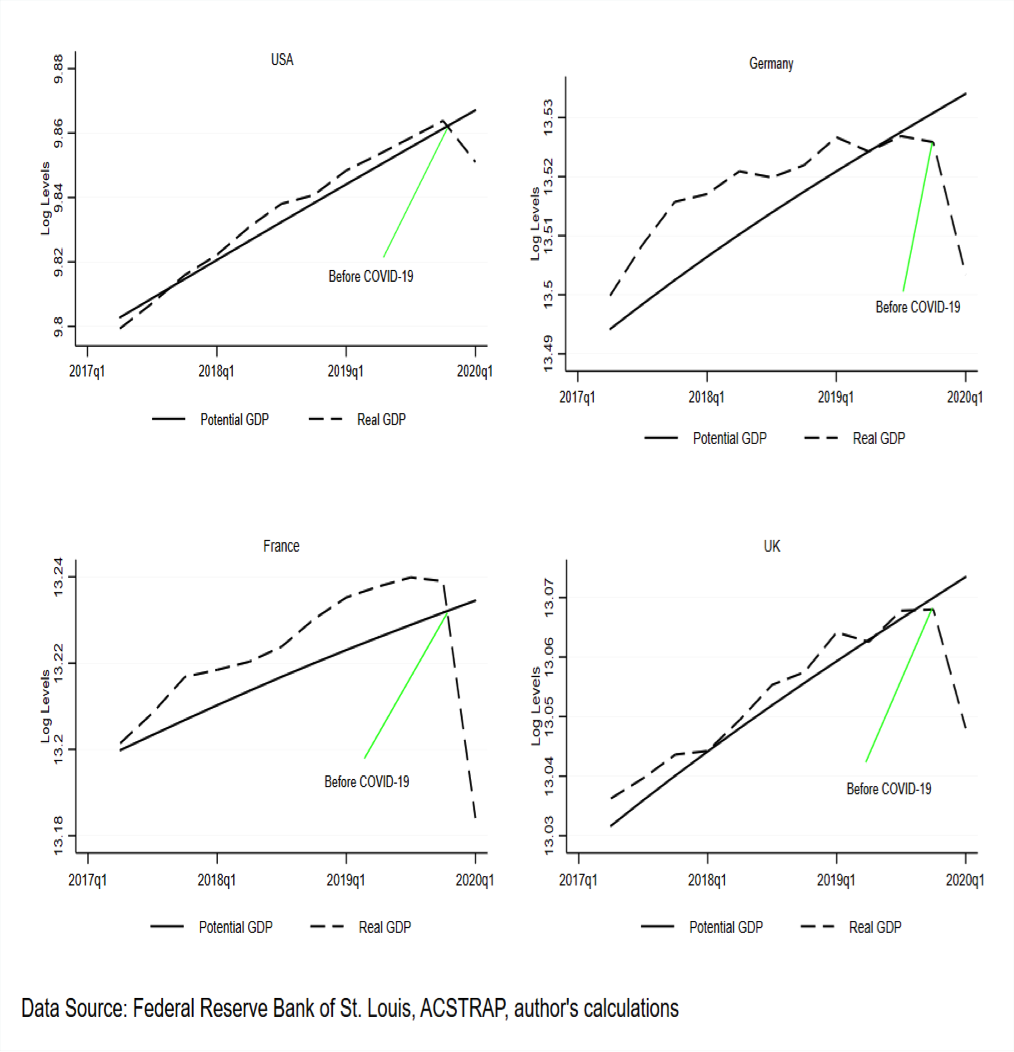

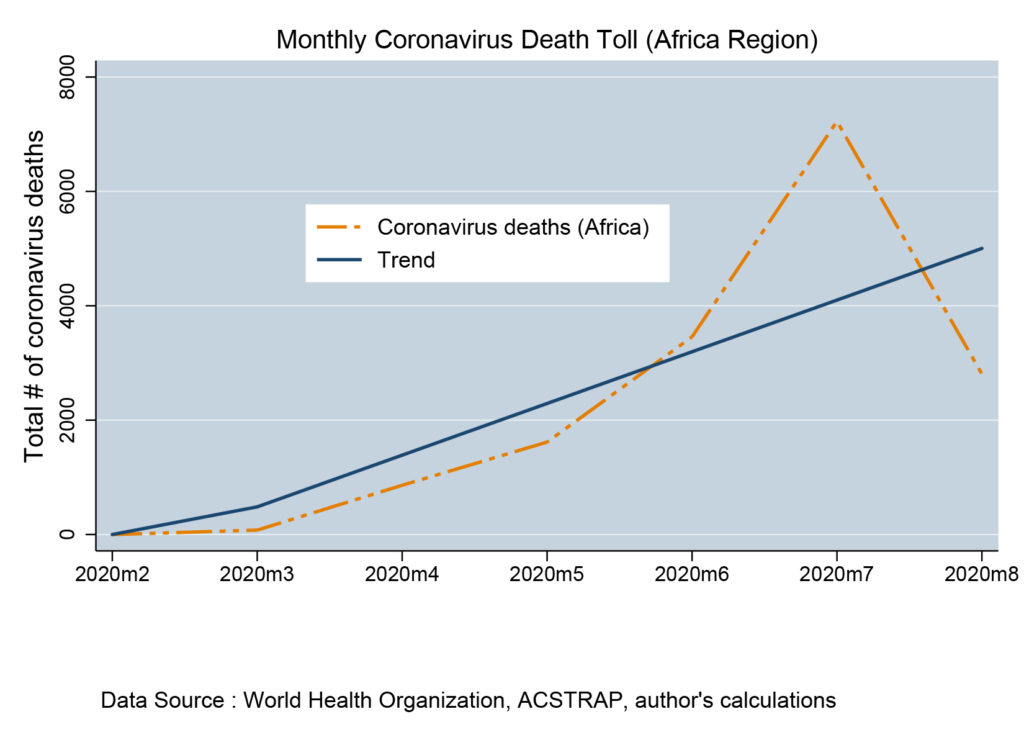

Commodity prices tumbled drastically in the first quarter of 2020 at the onset of the pandemic, coinciding with a sharp deterioration in foreign demand. 1 See Figure 7 for empirical evidence on global economic performance.Hence the recent poor economic developments amid the pandemic emphasize the major limitations placed upon Sub-Saharan Africa’s future growth perspective. Financial flows (for example, foreign direct investments) remain instrumental in stimulating economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa.2Kinda, Tidiane, Jean-Louis Cambesa, Patrick Planea, and Rasmane Ouedraogo.”Financial flows and economic growth in developing countries” Economic Modelling 83 (C), No. 2(2019):195-209.Data suggest that the trade channel remains the most potent source of foreign exchange reserves for central banks (see Table 5 for empirical evidence) and tax revenues for Sub-Saharan African governments (see Table 3 for empirical evidence).

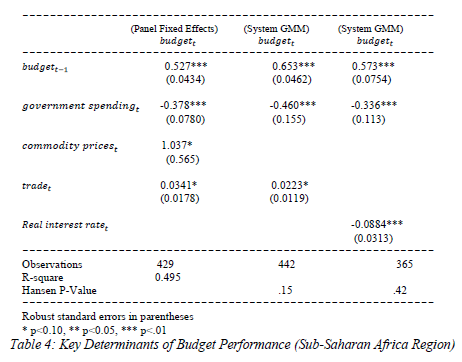

Data compiled from an unbalanced panel of 48 Sub-Saharan African countries affirm that trade performance explains close to 38 percent of variations in federal budget performance, 23 percent of variation in central government debt, and 36 percent of variation in gross fixed capital formation (see Table 6 for correlation evidence). Consequently, it would be logical to expect mounting macroeconomic instability in Sub-Saharan Africa, following the recent trade suspension measures implemented by Africa’s key trading partners (for example, USA, EU, India, and China).

Nonetheless, African policymakers can still play a decisive role in mitigating the cost of pandemic on economic performance. The focus should be placed on minimizing the impact of the pandemic in key specific areas: trade performance, external debt, pension fund assets, and financial stability. This brief report discusses several economic stabilization policies to contribute to the set of existing policy recommendations already put in place by African policymakers to confront the ubiquitous threat of the COVID-19 pandemic.

II. Revitalizing Trade Performance

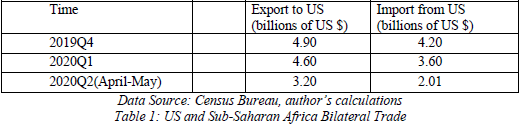

Trade restrictions imposed by African policymakers in the early stages of the pandemic have undoubtedly slowed down trade in Sub-Sharan Africa (see Table 1 for US-Africa evidence). On one hand, Intra-Africa trade performance is likely to continue to deteriorate due to enforced curfews and heightened border checks implemented during the pandemic. For instance, cross-border exporters of perishable goods face a relatively dire predicament, mainly because shipment delays across the borders are likely to have a negative impact on the quality of livestock and produce, due to poor food preservation infrastructure.

On the other hand, the ongoing import and export restrictions of key products imposed during the pandemic have already begun to negatively impact international trade in Sub-Saharan Africa: import of US goods by Sub-Saharan African countries dropped by a staggering 50 percent from 2019Q4 to 2020Q2, whereas Sub-Saharan African export to US also fell by approximately 34 percent within the same period (see Table 1).

Additionally, the rapid decline in commodity prices from January 2020 to April 2020 has also strained the flow of export revenue for African exporters, including local African businesses that rely on export proceeds to finance merchandise import. Nevertheless, as COVID-19’s infection rate continues to decline progressively, more countries are currently loosening trade restrictions and reopening their trading ports.3 Sallent, Mickaël. “Tourism in Africa: Virtual safaris kick in as countries slowly open to tourists”. Coronavirus, August 16, 2020, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/web-features/coronavirus/tourism-africa-virtual-safaris-kick-countries-prepare-reopen-tourists.Subsequently, policymakers around the globe are also hastening countercyclical measures to sew up and jump-start their economies in light of poor economic performance catalyzed by the ongoing pandemic. 4 “Kenya: Tax relief measures include reduced corporate tax rate (COVID-19) “. Insights, April 1, 2020, https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/04/flash-alert-2020-139.htmlFor Sub-Saharan Africa, reducing trade licensing fees, strengthening the supply chain channels, containing corruption, and preventing illicit trading activities could make a vital difference in revitalizing export performance.

2.1 Reducing Fixed Costs Associated with Export

One way to stimulate export performance without increasing the velocity of government debt would be to temporarily reduce any administrative fixed costs associated with export (for example, export registration fees and regulatory capital that exporters must pay to be eligible to export commodities should be reduced). Reducing these fixed costs would provide the necessary momentum for exporters to absorb the negative pressure on export revenue caused by the pandemic.

2.2 Strengthening Port-Centric Logistics and Railway Transport Infrastructure

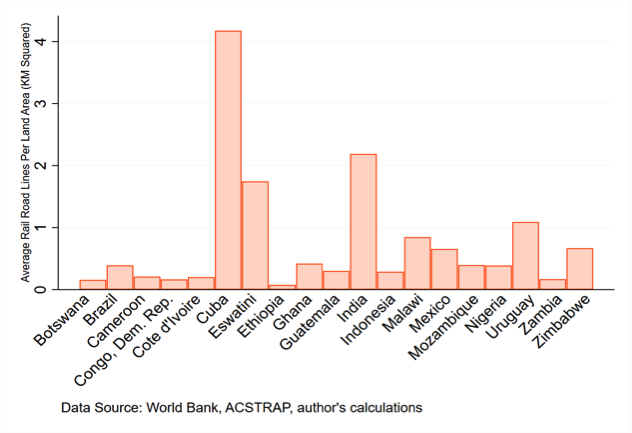

COVID-19 pandemic exposed some vulnerabilities in port-centric logistics and transportation systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. The restrictive trade measures implemented by African governments in response to the pandemic triggered several problems such as port congestion and long shipping delays. Certainly, revitalizing trade in this current environment would require reinforcing freight transport infrastructure and improving port-centric logistics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Poor road transport infrastructure is widely known to be a relevant factor hindering Intra-Africa trade. 5Donaldson, Dave, Amanda Jinhage, and Eric Verhoogen. “Beyond borders: making transport work for African trade”. Growth firms, March 2017, https://www.theigc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/03/Transport. Additionally, Figure 1 shows that low railway density could also be another significant factor explaining poor trade performance between African countries.

Figure 1: Railway Density (Average, 2005-2019)

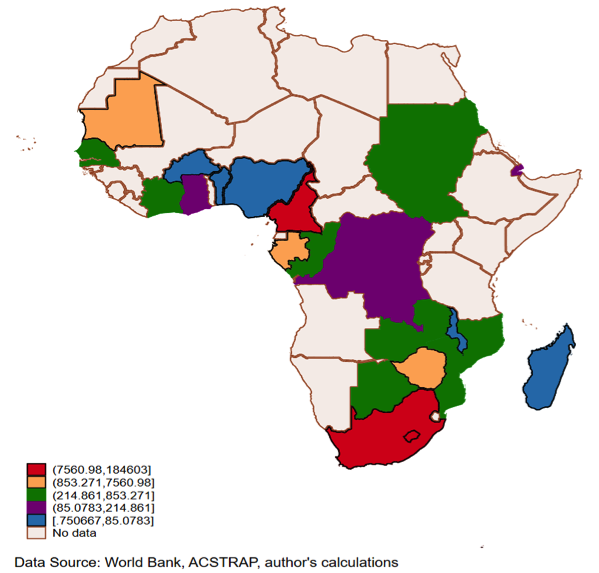

Nonetheless, the increase in curfews and border checks caused by the recent pandemic will likely slow down cross-border trading due to poor road and railway transportation infrastructure. Figure 2 also shows a relatively poor level of economic activities taking place via railway in Eastern and Western Africa; hence the need to increase railroad density in Sub-Saharan Africa. Prioritizing railway transport infrastructure over other forms of transportation systems (for example, road transport) would be more cost effective in the long run (for example, less fuel per ton mile) and provide greater social external benefits (for example, less accident and faster distribution of goods). Furthermore, reinforcing port-centric logistics will also be key in minimizing the impact of COVID-19 on trade performance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Port congestion caused by the increased number of quarantined vessels amid the pandemic augmented pressure on inland container depots, hence showing vulnerability in port-centric logistic systems across Sub-Saharan African countries. 6 “Port of Durban Quarantines Hapag Vessel as it Manages with COVID-19”. The Maritime Executive, July 28, 2020. https://www.maritimeexecutive.com/article/port-of-durban-quarantines-hapag-vessel-as-it-manages-with-covid-19. However, expanding port capacity or investing in bonded warehouses could be effective temporary measures needed to bolster port efficiency and improve trading activities amid the pandemic.

Figure 2: Volume of Goods Transported by Railway in Millions (Average, 2005-2019)

Additionally, African policymakers can improve commercial screening conventions by establishing transparent disinfecting zones (TDZs) at the key commercial airports, border posts, and key seaports, where commercial cargos and inland containers would be inspected, screened, and disinfected appropriately in a timely fashion. This process would systematically reinforce credibility in the African supply chain system.

2.3 Preventing Corruption and Illicit Trading Activities

For Sub-Saharan African countries, port congestion amid the pandemic is likely to bolster corruption (bribery) and illicit trading activities (theft). Local law enforcement agencies should step-up joint maritime and cross-border patrols to ensure fast movement of goods across borders and seaports. Policymakers should also establish an active fraud-alert line that can be used to report bribery and any suspicious trading activities.

III. Minimizing External Debt Pressure

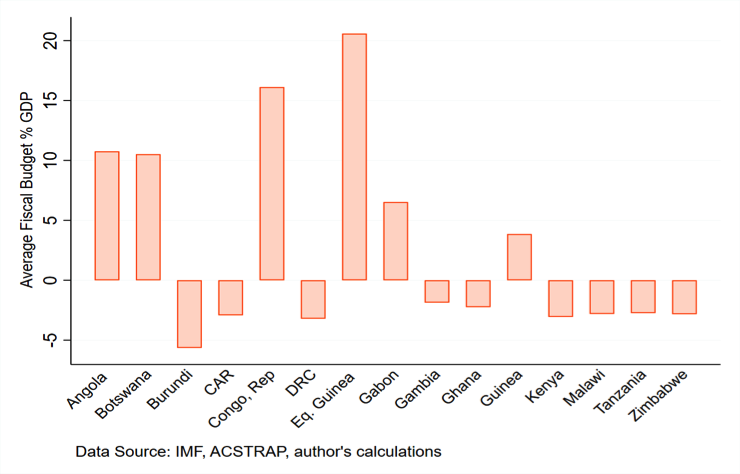

For those Sub-Saharan African countries with tighter fiscal space (see Figure 3), the drastic collapse in global trade and commodity prices amid the pandemic will inevitably exacerbate debt levels. On the other hand, the major oil exporters in Sub-Saharan Africa are more likely to suffer less brunt from adverse terms trade shocks, due to stronger historical fiscal performance induced by better tax revenue management.

Figure 3: Fiscal Budget Balance % GDP (Revenue, excluding grants – Government Expenses, Average, 2005-2019)

Eventually, poor trade performance amid the pandemic will negatively impact tax revenue (see Table 1 for empirical evidence), hence forcing those African countries with weaker fiscal space to rely further on external debt as means to finance government operating activities. One way to minimize pressure on the external debt without putting downward pressure on economic growth would be to defer interest payments. Sub-Saharan African countries should form a coalition to negotiate debt service terms with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank to reduce external debt pressure during the ongoing pandemic.

Additionally, those countries facing acute budgetary problems due to the pandemic should be taking more proactive and counter-cyclical fiscal measures. These specific countries should be borrowing locally or through temporary international credit facilities that provide lower interest rates and then rely on fiscal consolidation to lessen pressure on external debt.

Borrowing locally would minimize pressure from exchange rate risks and reduce the imminent threat of balance sheet effects. Alternatively, African countries with acute fiscal issues should also consider the IMF’s Rapid Credit Facility (RCF), which provides guaranteed financial assistance to countries facing drastic balance of payments issues stemming from terms of trade shocks, including natural disasters such as the ongoing pandemic. RCF provides almost no conditionality; the lending terms are extremely fair and flexible: RCF offers zero interest rate with a 10-year maturity period to repay the loan.

Fiscal consolidation should be achieved preferably by relying on indirect tax instruments (for example, import taxes) and also by reducing some recurring government expenditures (for example, top government officials with high salaries should be encouraged to take a temporary pay cut amid the ongoing pandemic).

IV. Strengthening Public Pension Funds

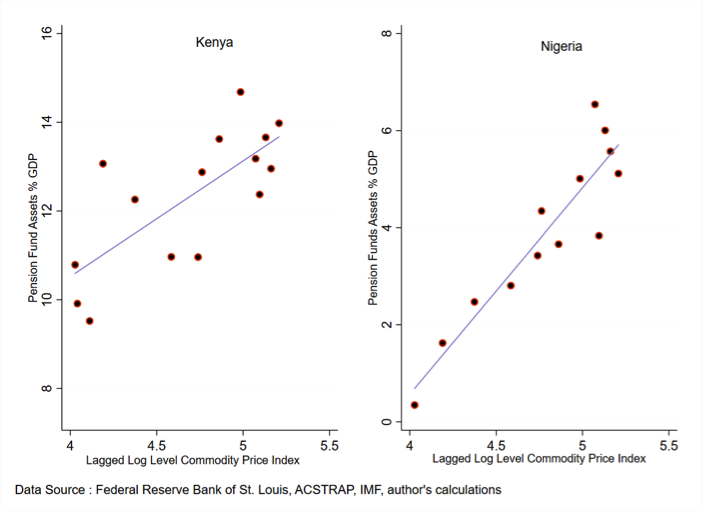

Available data show that the lagged-effect of commodity prices (for example, the third-year lag) explain over 70 percent of variation in pension fund performances in countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Nigeria (see Figure 4 for some empirical evidence). Hence the calamitous downfall of commodity prices from January to April 2020 will likely impede the ability of African governments to properly finance their public pension funds.

Furthermore, temporary layoffs, coupled with government spending cuts amid COVID-19 pandemic could have a long-term negative impact on pension fund growth unless government officials can find alternative sources of funding to support their public pension funds in a tight fiscal environment exacerbated by COVID-19 pandemic. Relying on foreign aid to partially finance pension transfers has always been a prominent option for Sub-Sharan African countries, but one that seems temporary, primordial, and procyclical.

Figure 4: Commodity Price Fluctuations & Pension Funds Performance

Instead, the long-term priority of African governments should be to stabilize public pension funds in such a way that public pensions funds remain buoyant regardless of whether economic performance is sinking or improving. This latter objective can be achieved by relying on a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF): a pool of assets that can be directly managed by national governments to achieve a specific mandate (for example, to support pension fund growth or the fiscal budget).

Sub-Saharan African countries can support their public pension funds by funding SWFs from export tax revenue. An SWF can be invested in various domestic and foreign assets (for example, asset-backed securities, stocks, private equity, real estate, and fixed-income assets). SWFs would provide greater balance and stability to African public pension funds: hence in recession time, Sub-Saharan African countries would rely on SWFs to channel investment proceeds towards replenishing their public pension funds or supporting government transfer payments. Ultimately, the main idea is that an SWF would act as an automatic stabilizer for public pension funds in Sub-Saharan Africa.

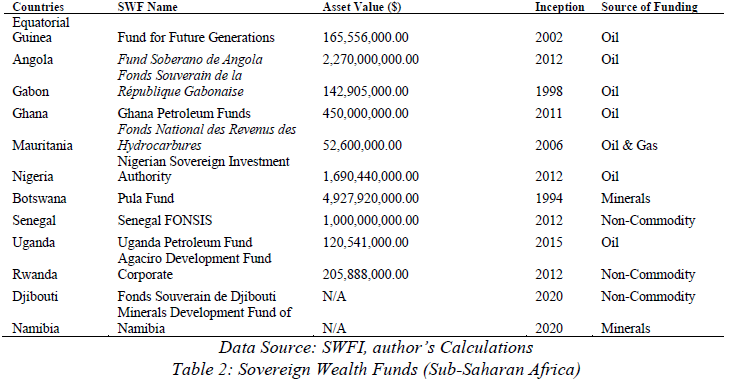

According to the sovereign wealth fund institute (SWFI), roughly 25 percent of Sub-Saharan African countries possess an active sovereign wealth fund (See Table 2). The SWFs listed in Table (2) are mainly mandated to utilize investment proceeds to either finance developmental goals, preserve national wealth, or to stabilize the fiscal budget amid commodity price volatility or poor export performance.

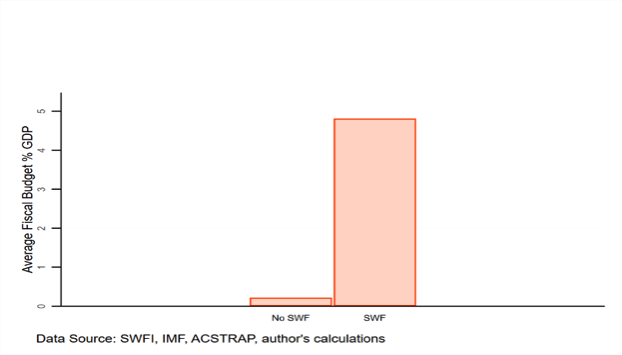

Namibia and Djibouti have recently joined the list countries with active SWFs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Other prominent African countries such as Cote d’Ivoire (the largest cocoa exporter in the world), Cameroon, Niger, Mali, and Chad could better manage their public pension funds by investing a portion of their export revenue into SWFs and then utilize the proceeds from these funds to smooth out unexpected shocks to their public pension funds. Effectively, data reveals that those Sub-Saharan African countries with sovereign wealth funds (mostly the top oil exporters) do show better fiscal performance in contrast to their counterparts with no active SWFs (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Sovereign Wealth Funds and Fiscal Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa

V. Restoring Financial Confidence and Stability

For commodity-dependent-developing countries, negative commodity price shocks are often followed by rising non-performing loans and falling demand deposits, which in turn forces local banks and other financial institutions to decrease lending exuberantly.7Kinda, Tidiane, Montfort Mlachila, and Rasmane Ouedraogo. “Commodity Price Shocks and Financial Sector Fragility.” IMF Working Paper (Washington: International Monetary Fund), 16/12 (2016). COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected commodity price momentum and slowed down economic activities in Sub-Saharan Africa. Hence the current economic environment necessitates African central banks to take aggressive steps to restore confidence in the banking sector and financial stability.

Attaining these latter objectives would require providing direct support to commercial banks whose balance sheets have been severely weakened by the pandemic, including those commodity exporters unable to obtain loans (crédit de campagne) and facing extreme pressure from poor commodity prices. Effectively, some African central banks have already begun to gradually reduce reserve requirements and key policy rates as means to increase confidence by driving down the cost of borrowing in both the secondary and primary markets.8Konandi M Jean. “UEMOA : La BCEAO réduit ses taux directeurs pour accompagner la relance économique “. Sika Finance, June 23, 2020. https://sikafinance.com/marches/uemoa-la-bceao-reduit-ses-taux-directeurs-pour-accompagner-la-relance-economique_22962.

Nonetheless, some financial institutions (for example, the under-capitalized banks weakened by non-performing loans amid the pandemic) may have severe liquidity issues preventing them from accessing the central bank’s discount window or even the interbank market. Therefore, in order to stabilize the financial sector and avoid bank failures, African central banks would have to find unorthodox ways to provide liquidity to those fragile banks affected by the pandemic.

A possible solution would be to create a special liquidity facility window for those fragile banks that are illiquid, overleveraged, and cannot meet both Basel I and II capital requirements. Additionally, to reduce the inflation bias and create a better monetary policy cushion, those African central banks operating with intermediate targets should consider raising these targets temporarily. For instance, increasing an inflation target or a monetary aggregate target would provide more room for monetary policy expansion, reinforce central bank credibility, and minimize the time-inconsistency problem.

Commercial banks should also consider loan refinancing as a temporary option for commodity exporters facing difficulties in keeping with interest payments due to export delays and feeble export prices; this would restore consumer confidence and stability in demand deposits. From a monetary policy perspective, increasing the monetary base may not necessarily increase confidence in bank lending, particularly because uncertainty in macroeconomic developments caused by the pandemic may force bank managers to delay loans temporarily. Thus, to prevent excessive cuts in lending amid the ongoing pandemic, African central banks should consider imposing temporary sectorial loan coefficients on borrowed reserves. This policy would force commercial banks that borrow reserves from the central bank to lend a given percentage of borrowed reserves into key sectors of the economy (for example, the export sector).

Annexes