Imperial Reckoning: an exceptional investigation into the violence and brutality which characterized the end of empire in Kenya

Liam Palmbach, Director, Youth, Gender, and Vulnerability Policy Lab

lpalmbach@africacfsp.org

In ‘Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya’, author Caroline Elkins provides unique insight into late-colonial Kenya after having spent a decade of research in archives and conducting interviews with survivors of all sides of the Mau Mau rebellion in the 1950s. She provides a picture of an already racist regime whipped up in a frenzy of violence comparable to the worst atrocities of the second world war. Reading this account, one is especially struck by the similarities among the British colonial regime in 1950s Kenya and other genocidal regimes throughout history. Indeed, when racism and subjugation are the bedrock of rule, which is also devoid of democratic legitimacy, the gradual escalation of events to the point of inexplicable violence becomes the logical conclusion of such circumstances. This is one of the first in-depth investigations of Mau Mau, and Elkins provides a service in exposing the truth about the end of empire in Kenya.

The Beginnings of Colonialism

An interesting and important fact which Elkins draws attention to is that the types of people who ran the British empire almost universally came from a specific clique of British society. Many went to the same schools, where they had an imperial, ruling class ethos instilled in them. Bound by a shared aristocratic ideology and a belief in the civilizing mission of the empire, this small cadre from Great Britain would come to exercise outsized influence across the globe.

Starting in the early 1900s, settlers began relocating to Kenya to take advantage of the promise of cheap land and labor as well as access to capital. In order to keep this promise, the colonial government created a number of regulations. Firstly, many Kikuyu whom had occupied some of the most fertile land in the country were pushed onto reserves. The aim, as Elkins puts it, was to create a landed plutocracy similar to that which existed in the US South around the same period. This process carried especially significant cultural implications in Kikuyu society, where the acquisition of land played a central role in Kikuyu men and women being welcomed into adulthood. Secondly, the population was heavily taxed, thus forcing them into wage-labor. With a large labor pool and no labor rights to speak of, labor was kept cheap and plentiful for the settler population. Thirdly, the authorities invented the ‘kipande’ pass, an identity document featuring basic personal information and work histories, and which hung in a metal case around one’s neck for the purpose of monitoring and restricting movement. Finally, regulations were introduced to limit African agriculture to maize production, thereby eliminating any potential competition with European farmers.

Such circumstances played a significant role in stirring resentment amongst the Kikuyu population in Kenya. Amplifying this discontent was the creation of the chief system. Prior to colonial rule, the Kikuyu did not have a chief system but instead relied on elders’ councils for making decisions. By instituting a system of powerful chiefs in Kenya, whose primary responsibilities included collecting taxes and encouraging wage labor, the British colonial authorities created valuable allies who facilitated rule, but who came to be viewed with resentment among much of the population.

The Start of Mau Mau

In the aftermath of the Second World War, many Kenyans who had fought for Britain in Asia returned to find conditions in their home country significantly deteriorating, as the resettlement of Kenya with Europeans was accelerating due to the opportunity it offered for economic advancement to ex-British servicemen. Combined with mounting resentment of colonial policies and a broader anti-colonial global backdrop, Kenyan political leaders began making demands for representation and independence.

Tensions eventually came to a head in 1952, which marked the start of sustained violent resistance to the empire. The resistance was distinguished by large oathing ceremonies whereby those wishing to fight would undergo the Mau Mau oath for land and freedom. The oath was kept secret and adherents were sworn not to reveal the specifics of it. What followed were attacks on settler property and loyalist Africans. For settlers, the colonial administration, and the press back in the United Kingdom, the Mau Mau oath represented the depths of inhuman barbarity, untamed savagery, and something that must be crushed at all costs. The portrayal of Mau Mau as such, along with the refusal to acknowledge any legitimate grievances amongst the population, is key to understanding the years which followed. Every attack further amped up settler hysteria and demands were made for a harsh clampdown.

The assassination of loyalist senior chief Waruhiu (known as ‘Africa’s Churchill’) that year was a turning point. It was after this assassination that Governor Evelyn Baring declared an emergency. The ensuing ‘Operation Jock Scott’ saw the arrest and imprisonment of Kenyan anticolonial political leaders, among them Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Ngei, Bildad Kaggia, and Fred Kubai. Unforeseen by the colonial authorities, this move turned Kenyatta into a martyr and unifying symbol, and demands for his release became a useful rallying cry. In addition, the imprisonment of political leaders meant the leadership of the resistance movement was passed into the hands of younger radicals.

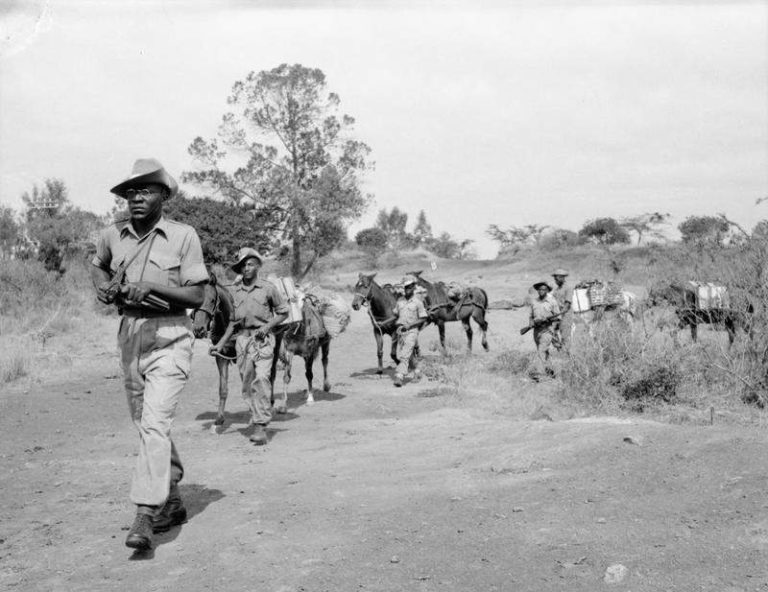

What ensued was a series of Mau Mau attacks and then British counterattacks which were often larger and more indiscriminate in scope. The Mau Mau war turned into a military conflict which mostly took place in the forests, where British and loyalist African forces fought Mau Mau adherents. Dispatched as from nearby Uganda as part of his company of the King’s African Rifles, one Idi Amin was involved in suppressing the Mau Mau rebellion in the early 1950s. Though by 1954 most military operations against Mau Mau fighters would come to an end, the state of emergency would not be lifted until 1960. The emergency was initially expected to be over within three months, but when Mau Mau did not collapse, the colonial government began constructing of camps for detaining much of the Kikuyu population. What occurred off the official battlefield was in many ways more significant than what occurred on it, and is the primary focus of Elkins’ book.

The Pipeline

The emergency regulations allowed the colonial government to disband political organizations, enact curfews, exact communal punishment, suspend due process, and create a complex system of detention camps and concentrated villages. In public, Governor Baring spoke of the ‘rehabilitation’ efforts designed to win over the population, but in reality, he was constructing an elaborate system throughout the early 1950s which served the explicit purpose of punishment, torture and enslavement.

The system devised by the colonial government came to be referred to as the ‘pipeline’ which involved transit camps, works camps, and reserves. Detainees were first placed in transit camps where it would be decided whether to deport them to the reserves or to send them to the punitive detention/works camps. The transit camps were overcrowded, rife with disease and malnutrition, and some would stay in these camps for months on end while waiting for the authorities to classify them according to a color system. Those deemed ‘whites’ were considered to have not been involved in Mau Mau and were repatriated to the reserves, while those determined to be ‘greys’ were considered to have Mau Mau sympathies who needed to be ‘reformed’ and would thus be sent to the works camps. Finally, ‘blacks’ were allegedly hardcore Mau Mau adherents deserving of special brutality.

The first wave of roundups of the Kikuyu population began at the end of 1952, but many more would follow. One of the most famous mass detentions was Operation Anvil in 1954. Described as ‘gestapo-like’, Operation Anvil involved ambushing the civilian Kikuyu population of Nairobi during the night and subsequently placing them in barbed-wire transit camps. Once in the transit camps, one way of determining a detainee’s color classification was by relying on Kikuyu loyalists. After Operation Anvil, those rounded up were paraded in front of hooded loyalists who often used their position and authority to exact vengeance on personal enemies by identifying them as Mau Mau, thereby sealing their fate.

Those deemed unfit to be sent to the reserves, the ‘blacks’ and ‘greys’, were sent to works camps, where their labor was used to fulfil the Swynnterton Plan, a mass agricultural and infrastructure development project (which included the construction of what is today Kenyatta International Airport). Conditions in the works camps were appalling, and random beatings, hangings, and murders of prisoners occurred daily, all while prisoners were forced to work long hours in grueling conditions with little to no food or water. The International Labor Organization would eventually criticize the government in Kenya for enslaving mass amounts of the population, allegations which the colonial office in London promptly dismissed.

Ubiquitous in all the camps was a process called ‘screening’. A euphemism for torture, screening involved severe beatings, castration, electric shocks, mutilation, and much more amidst demands for information or confession of one’s Mau Mau oath. Screening would be carried out by the Special Branch, which earned itself the nickname ‘Kenya’s SS’. Psychological torture was utilized in addition to physical torture, where detainees were told stories of what became of their families. Katherine Warren-Gash, a particularly cruel camp superintendent at Kamiti women’s camp, tracked down detainees’ families and had them write letters pleading for their relatives to confess. Alongside regular torture, anti-Mau Mau propaganda would blare through loudspeakers in many camps, exalting the might of the British Empire and demanding detainees confess their oath.

A great deal of emphasis was put on extracting oath confessions from detainees. Only by confessing their Mau Mau oath could detainees be moved down the pipeline, which would result in a change of classification. In doing so, a ‘grey’ or ‘black’ could be re-classified as a ‘white’ and be sent to the reserves. The focus on confession was drawn from the ‘hard scientific evidence’ provided by ‘ethno-psychiatrist’ JC Carothers, whom the colonial government commissioned to produce ‘The Psychology of Mau Mau’. In his work, Carothers posited that the Mau Mau rebellion was not political but rather psychopathological and something which could be dealt with by extracting confessions of one’s Mau Mau oath. Employing pseudo-science to confirm Mau Mau as uniquely savage played an important role in justifying the rampant brutality which existed in the camps, and may in part have been borne out of a desperation to maintain Britain’s carefully-crafted image of benevolent, civilizing colonizer. Only through providing ‘proof’ of the alleged savagery of Mau Mau could the government justify all manner of cruelty in suppressing it. Regardless of the reasons, confession played a crucial role in determining whether a detainee had a chance of being moved down to the pipeline. When colonial authorities made oath confession a focal point, it gave the oath stronger symbolism and transformed it into a symbol of unity and resistance. Nonetheless, many were eventually ‘broken’ and confessed in the hope of being transferred out of the works camps.

However, if one had confessed their oath, they would have found that conditions in the reserves differed little from those in the camps. Beginning in June, 1954 and over the following 18 months, over one million Kikuyu were herded into 804 makeshift villages surrounded by barbed wire, trenches, and watchtowers. To the public, the colonial government portrayed these newly-formed villages as sites to civilize and rehabilitate the population, transforming them into obedient colonial subjects. In reality, they lacked food, water, medical facilities, shelter, and sanitation. Detainees were prevented from cultivating food in the villages and were only released once per week to their farms to collect food. But with no one to tend to them, the farms quickly fell into disrepair, and those who tried to escape the villages were shot. Women made up most of the population of these villages, and there was a strong desire to punish women for allegedly feeding Mau Mau fighters. Beatings, rapes, and public hangings were widespread and systemic. The reserves, therefore, had become detention camps in all but name. Through Elkins’ many interviews with women survivors, most recall the lack of food more than anything else. Governor Baring refused to acknowledge the widespread food scarcity in the reserves, which was reaching famine levels. While the Red Cross was involved in food distribution during the emergency, relief workers were under the governor’s direct control and distribution was focused not on areas most in need but on those where loyalists resided.

Elkins exposes a particularly striking dynamic, whereby the colonial government was well-aware of the conditions which existed in the camps and the illegality of its actions. Indeed, colonial officials in Baring’s government deliberated over how to circumvent the European Convention on Human Rights, which was written to specifically avert the conditions which arose in concentration and POW camps during the Second World War. They did so by citing article 15, which permitted grounds for abrogation (though torture was still prohibited regardless of the invocation of article 15). In reality, most colonial officials considered Africans not civilized enough to be accorded full rights and Mau Mau was thought to be a form of evil bestiality in a category of its own, a mode of thinking, it should be pointed out, which permeates all genocidal regimes. Indeed, the camps established in Kenya bore striking similarity to Soviet gulags, Japanese POW camps, and Nazi concentration camps. In Kenya, as in the other cases, a tension existed between the need to keep prisoners alive to use their slave labor on the one hand, and the impulse to punish, debilitate, and exterminate the population on the other. As a result, many were kept on the brink of death, while those who perished were buried in mass graves. Also similar to the camps of the Second World War, the regime blurred the lines between inmates and personnel. Some detainees would collaborate to elevate their position within camps, some would be given easier jobs, and others would join in on interrogations. Keeping prisoners divided amongst themselves was key to the running of the camps. In certain camps, prisoners would be greeted with signs reading ‘He Who Helps Himself Will Also Be Helped’ and ‘Labor and Freedom’, hardly a far cry from similar expressions emblazoned outside Soviet gulags or Auschwitz’ infamous ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’. Therefore, less than a decade after the end of the Second World War and contrary to the historical narrative of post-war progress, the world would once again witness acts of barbarity that were thought to have been laid to rest.

Resistance, Suppression, and Opposition

Through her many interviews with survivors, Elkins paints a picture of life inside the camps. One learns that while some prisoners eventually confessed, worked with camp administrators, or turned on their fellow prisoners, others still developed their own modes of resistance. In many camps, prisoners formed committees, established rules, and built of relationships with sympathetic guards who could smuggle their messages out. They also developed unique communication techniques with prisoners placed in other compounds, such as by shouting and feigning insanity. Some of the more political, hardcore detainees were kept at Manda Island, and they managed to write dozens of letters to officials both in Kenya and in the United Kingdom describing their conditions and hoping their pleas would fall on sympathetic ears, and with considerable success.

However, such actions could mean a death sentence if and when camp authorities discovered them. Guards were also frequently shifted around in order to stymie any budding solidarity with prisoners. In broader society, the colonial government cemented divisions between loyalists and Mau Mau (and the conception that one could be neither was not accepted). For example, African loyalists were issued a ‘loyalty certificate’ which gave them freedom of movement, tax exemption, commercial licenses, and the right to vote in limited elections. However, regardless of whether a prisoner confessed their oath, anyone who had been in the pipeline (which, as has been seen, was often chosen at random) would never be accorded such benefits. Furthermore, in 1955 the colonial government, including Churchill and his cabinet, approved an amnesty for crimes committed since the start of the emergency, thus making official policy out of what had already been an ongoing practice. For accused Mau Mau, this meant no prosecution for capital crimes, though they would still be sent to detention camps in the pipeline (only this time without a sham trial). Meanwhile, it excused all those acting on the government’s behalf to suppress the rebellion and ensured no convictions would follow.

Back in the United Kingdom, dissent against the situation did exist, and grew stronger as the years went by. Labour MPs Barbara Castle and Fenner Brockway proved valuable voices of opposition and made attempts to draw attention to the issue after leaks exposed ongoing abuse. In 1954, police officer Arthur Young was dispatched to Kenya to oversee police reforms, but resigned from his post in a matter of months due to disgust at the ‘revolting crimes’ taking place and the government’s refusal to allow the police to act independently of the governor. The resignation of Young sparked outrage in the House of Commons. Over the coming years, a slew of other abuses came to light which illustrated the conditions in Kenya, such as the flogging to death of detainee Kamau Kichina. The exposure of individual cases had the effect of humanizing resistance to the empire and played a large role in altering the British public’s perception of the war in Kenya towards the end of the 1950s.

Barbara Castle herself eventually visited Kenya, where individuals like officer Duncan McPherson informed her of the pipeline system, the forced labor, the torture, and conditions he described as worse than those he endured as a POW in a Japanese camp. Upon returning to Britain, Castle engaged in a media campaign, drawing the ire of the colonial office and colonial secretary Alan Lennox-Boyd in particular. Convincing the public of the true nature of events in Kenya proved difficult as the broader public had already been significantly misled about the situation. Nonetheless, more and more leaks came out as the emergency continued.

Things came to a head in a number of showdowns in the House of Commons, the first of which occurred in 1956. Labour MPs in parliament pressed Lennox-Boyd on the accusations of abuse. The colonial secretary, a master manipulator of information, quickly dismissed individual abuses as out-of-the-ordinary excesses and not illustrative of an otherwise humane system. Any abuse, it was asserted time and again, arose out of the unique savagery colonial forces were facing in fighting Mau Mau. In the rare cases that abuse by specific officials was exposed, convictions were rare and sentences were extremely lenient. There was no notion of command responsibility (which was used to convict Nazi war criminals) despite the widespread evidence of state-sanctioned terror.

There were also those on the ground who tried to ameliorate the situation, such as Thomas Askwith, appointed head of community development and rehabilitation. An idealist, Askwith tried but failed to bring about more humane treatment of prisoners. His budget was small and the colonial government ensured that he had no real power in Kenya. One of the administrators under his control, Eileen Fletcher, left her post and came forward to publish a three-part series in 1956 entitled ‘Kenya’s Concentration Camps – An Eyewitness Account’. In 1957, when Askwith himself lodged a number of complaints, he was summarily dismissed.

The missionary community, for its part, was divided over how to respond to ongoing events. While Catholic missionaries took the side of the government, protestants found themselves walking a tightrope between criticizing the regime and refraining from getting involved (as they were only in Kenya at the governor’s behest).

Eventually, the colonial government allowed for a visit of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) to Kenya to inspect conditions and allegations of abuse. After a carefully choreographed visit, the CPA issued a positive report on the state of affairs in Kenya. This was used by Lennox-Boyd in the House of Commons to refute allegations lodged by an increasingly angry Labour Party.

The Final Years of the Emergency and the End of Empire

In 1957, the colonial government was under pressure to end the emergency, but thousands still remained in the punitive camps. Furthermore, the government was concerned about the effects of releasing political prisoners. It was thus decided that new legislation must be enacted allowing for the permanent exile of political prisoners, while those remaining in the pipelines must be ‘broken’ and pushed through as quickly as possible. In what became known as ‘Operation Progress’, Terence Gavaghan, a particularly ruthless colonial official, developed the ‘dilution technique’, a relenting barrage of physical and psychological torture which successfully broke many prisoners by extracting confessions.

Meanwhile, opposition continued. 1957 saw the first elections where Africans gained seats in local parliament. Though their abilities were severely restricted, many did speak out against the ongoing abuses. By the end of 1958, multiple reports continued to find their way to the press in the UK, such as a letter from Kenyan political leaders held at Lokitaung which was published in The Observer. Each report furthered outrage, but still little was done to change the situation on the ground. A vote on conducting an independent investigation of the government in Kenya was eventually held in British parliament, and the Conservative majority ensured that it failed. The down vote in the House of Commons was interpreted as a green light for the colonial government to continue abuse unabated.

Then, in 1959, 11 detainees held at Hola camp were killed in what came to be known as the Hola Massacre. Though not an anomaly considering the events which had abounded for the better part of a decade, the government’s claim that the detainees died of poisoned well water was quickly debunked. The sloppy attempts to cover up the story only made matters worse, and even Conservative MPs like Enoch Powell criticized the MacMillan government for its handling of the massacre.

It is difficult to determine precisely how many were killed during the emergency. Officially, 11,000 Mau Mau adherents were killed during military operations, while 32 white settlers were killed. But that does not account for the total number killed in a war that was largely waged against a civilian population, a number Elkins estimates to be somewhere between 150,000 to 300,000.

After all that had occurred, the Hola Massacre played a pivotal role in sealing the fate of the empire in Kenya. When pitted against an international situation in which European colonialism was broadly seen to be in its final days, it became clear that maintaining the empire would be untenable. In 1959, Lennox-Boyd retired from the colonial office and was replaced by Iain MacLeod, who was appointed to oversee the dissolution of the empire in Kenya. The political prisoners were eventually released and the new Kenyan government which came to power in 1963 would inherit numerous problems from its colonial predecessor. Indeed, Elkins invites the reader to contemplate the aspects of continuity and change which accompanied independence. For some, independence proved bittersweet, as those who had been forced off their land often never got it back, and loyalists who facilitated colonial rule loomed large in the post-colonial period. Meanwhile, back in the UK, those responsible for the committal of atrocities did not face any consequences, as Terence Gavaghan was awarded an OBE, while Thomas Askwith was ostracized for the remainder of his life.

The Mau Mau war threatened to destroy a carefully-cultivated image of British trusteeship in Africa. For decades, liberals and conservatives alike believed in the ‘civilizing mission’ and the fundamental difference and benevolence of British imperialism, especially in contrast to its French, Belgian, and German counterparts, all of which had carried out genocidal wars in Africa. The relative lack of knowledge of atrocities carried out in Kenya (and other colonies) plays no small role in the persistence of that ideology today. By exposing the true nature of events in Kenya in the 1950s, Caroline Elkins finally lays the ideology of British exceptionalism to rest.