Social Policy in Sub-Saharan Africa and Colonial Institutional Legacies

Pandit Mami, Research Lead & Analyst, Foreign Policy & Diaspora Studies Policy Lab

pmami@acstrap.org

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Through political science research, we now know how the colonial legacies in the Global South informed the origin and path dependency of the region’s political and economic institutions. Despite this knowledge, social policy research focusing on government welfare spending outcomes has shed minimal light on how the fragility of these institutions impacts the quality of welfare service delivery.

In some ways, the field has encountered the following challenges because of this neglect: (1) limited quantitative evidence on the likelihood that the structure of institutions mediates the redistribution of government social welfare spending; (2) limited clarity on the social welfare spending threshold at which the effect of the structure of institutions is negligible.

The focus of this study is to address the first limitation mentioned above. Using seven Sub-Saharan African democracies as case studies, this report attempts to test the likelihood of colonial institutional structures mediating the quality of social services delivery. Through a confluence of quantitative methods and historical analysis, the report concludes that sufficient evidence suggests a significant linear relationship exists between government effectiveness and poverty alleviation. Sub-Saharan countries are more likely to achieve their poverty reduction goals by improving their quality of governance.

SECTIONS

THE ISSUE

THE CHALLENGE

IMPLICATIONS

DATA

RESULTS

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THE ISSUE

Efforts to promote equitable access to social welfare in Sub-Saharan Africa have largely focused on increasing government spending on welfare, invariably ignoring how the fragility of public institutions impacts welfare service delivery. As a result of this neglect, Sub-Saharan African nations fail to fully realize the redistributive effect of government social welfare spending in terms of poverty reduction and health care. Using seven Sub-Saharan African democracies as case studies, this report attempts to test the likelihood of colonial institutional structures mediating the quality of social services delivery.

THE CHALLENGE

Introduction

Attempts to explain social welfare regimes in the Global South have shed minimal light on how public institutions’ colonial origin informs social determinant outcomes in the modern era. Despite the tacit understanding among scholars that public institutions in the Global South are more fragile and particularistic than those in the Global North,1For more on the structural fragility of institutions in the Global South, please see: Kruks-Wisner, Gabrielle. Claiming the State: Active Citizenship and Social Welfare in Rural India. Cambridge University Press, 2018. limited quantitative work has been done to test the likelihood of these institutions mediating the quality of social welfare service delivery.2For more on how the historical development of Sub-Saharan African institutions and elite choice have mired social service delivery into a neo-patrimonial rabbit hole, see: van de Walle, Nicolas. “The Institutional Origins of Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 12, no. 1, June 2009; Mamdani, Mahmood. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. University Press, 1996; and Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. “Why Is Africa Poor?” Economic History of Developing Regions, vol. 25, no. 1, June 2010, pp. 21–50.

Two fundamental problems arise because of this neglect: (1) limited quantitative evidence on the likelihood that the structure of institutions mediates poverty levels regardless of social welfare spending outcomes; (2) limited clarity as to whether a welfare spending threshold exists in which these colonial institutional structures would likely have a negligible effect on the quality of service delivery.

The focus of this study is to address the first limitation mentioned above. Using Namibia, South Africa, Mauritius, Botswana, Ghana, Cape Verde, Sao Tome, and Principe—seven Sub-Saharan African democracies—as case studies, this report attempts to test the likelihood of colonial institutional structures mediating the quality of social services delivery and, subsequently, the likelihood of each of the social welfare interventions— government spending on education, health care, and social coverage—alleviating poverty.

The report concludes that sufficient evidence suggests a significant linear relationship exists between government effectiveness and poverty alleviation. In other words, Sub-Saharan countries are more likely to achieve their poverty reduction goals by improving their quality of governance.

Regarding the social policy variables, the evidence is insufficient to confirm a linear relationship with poverty alleviation. Despite these inconclusive findings, especially for education and social insurance spending, both linear regression models show a positive correlation between their unique intervention and poverty alleviation. Indeed, data sparseness and measurement constraints make quantitative cross-national studies challenging, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Literature Review

The dearth of research on how the structure of public institutions that emerged in the colonial era informs social service delivery is symptomatic of a much broader structural problem: limited research focuses outside of the advanced industrial capitalist nations.

Global South scholars kick-started the regional social policy literature by operating within the existing framework of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) literature. More specifically, they were primarily responding to the gaps in the OECD typology— how social welfare provision is designed and conceptualized. Ian Gough and Geoff Wood, for instance, question the fundamental assumptions in Esping-Anderson typology to include the role of other non-state actors in social policy provision.3Ian Gough and Geoffrey Woods (Eds) (2004), Insecurity and Welfare Regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. In the same vein, Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufman, classify social policy regimes in the Global South in regional clusters based on their spending levels in critical policy areas—pension, health, and education.4Haggard, Stephan, and Robert R. Kaufman. 2008. Others have gone on to design typologies based on who benefits from the implemented social policy.5Seeking, Jeremy. “Pathways to Redistribution: The Emerging Politics of Social Assistance Across the Global ‘South’.” Journal für Entwicklungspolitik : JEP 28.1 (2012) Social Services Abstracts.

Whereas the Global South social policy research has taken on a life of its own, we cannot ignore the fact that external validity concerns exported social policy research from the North to the global periphery.6Gough, Ian, and Geoffrey D. Wood. Insecurity and Welfare Regimes in Asia, Africa, and Latin America: Social Policy in Development Contexts. Cambridge University Press, 2004. Web.; Haggard, Stephan, and Robert R. Kaufman. Development, Democracy, and Welfare States: Latin America, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. Princeton University Press, 2008.; Huber, Evelyne, and John D. Stephens. Democracy and the Left : Social Policy and Inequality in Latin America. The University of Chicago Press, 2012. Relying on the Global South, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa, primarily for social policy theory testing—without integrating the region into the theory-building process—overlooks the region’s specific historical context. This approach minimizes the importance of understanding how the region’s unique institutional design could inform our broader comprehension of government social spending and social determinant outcomes.7The Global South social policy literature has benefited from OECD findings: See Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton University Press, 1990 and Pontusson, Jonas. Inequality and Prosperity: Social Europe Vs. Liberal America., 2005 for more on how Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) literature provided the conceptualization framework for the various welfare state typologies and the social risks they cover; and the type of political coalitions and state conditions that shaped welfare state development, respectively. Furthermore, Iversen, Torben and Thomas Cusack (2000). “The Causes of Welfare State Expansion.” World Politics 52 (April): 313-349, kick started the debate on the factors that cause the expansion of social policy regimes. In essence, exporting social policy research from the North to the South inadvertently sidelined the impact of extractive colonial institutional structures on social welfare service delivery (in this case, poverty levels). It is important to note that this impact is independent of government social welfare spending levels.

This is not to say that the Global South social policy literature has been oblivious to the fact that public institutions in the region, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, are fragile. Fewer studies have investigated, quantitatively, the degree of these institutions’ fragility or even explored ways to circumvent these structural pitfalls altogether. For instance, in lieu of structural reforms, is there a spending threshold in which these extractive institutions would have a negligible impact on the quality of welfare service delivery?8See Kruks-Wisner, Gabrielle. Claiming the State: Active Citizenship and Social Welfare in Rural India. Cambridge University Press, 2018 and Melani Cammett, and Lauren M. MacLean. The Politics of Non-State Social Welfare. Cornell University Press, 2014– for more on how citizens respond to fragile institutions and the inequality challenges that come with non-state welfare providers of social welfare, respectively. In addition, for more on how the oft-ignored historical informal and micro-level institutions shape the ways citizens interact with the state and society in social risk coverage, see MacLean, Lauren M. Informal Institutions and Citizenship in Rural Africa: Risk and Reciprocity in Ghana and Côte D’Ivoire. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

IMPLICATIONS

Historical Institutionalism

One of the central arguments of this report is that the historical path of sub-Saharan institutions should be considered in the overall debate on the redistributive effect of social welfare on poverty alleviation. The region’s public sector institution is mired in what Nancy Birdsall calls “a weak institutional trap,” specifically signaled by its weak middle-income class.9Birdsall, Nancy. 2007. Consequently, the rise of a large, vibrant middle-income class would address this problem, check elite abuse of power, protect property rights, and ensure adequate provision of public goods. Without these changes, elite interests must align with dismantling inherited colonial institutions to spur inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

Africa experienced divergent institutional development from the rest of the Global South. Acemoglu and Robinson trace this sub-Saharan African “weak institution trap” to a critical occurrence in the history of the institutional development of the continent.10Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. “Why Is Africa Poor?” Economic History of Developing Regions, vol. 25, no. 1, June 2010, pp. 21–50. It results from the fact that centralized states not only emerged later in the continent, but when they did, they were also “absolutist” and “patrimonial.” Slavery and colonialism exacerbated these conditions. Unlike other regions of the world, Africa never took a detour from these pitfalls.

As political scholar, Van de Walle points out, “political authority in Africa is based on giving and granting favor, in an endless series of dyadic exchanges that go from the village level to the highest reaches of the centralized state.”11Van de Walle, Nicolas. “The Institutional Origins of Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Annual review of political science 12.1 (2009): 307-27. CrossRef. Web. More notably, this prevalent neo-patrimonialism is laden with chronic corruption, which militates against the type of structure and designs essential to maintain more redistributive social welfare policies. Indeed, as Van de Walle puts it, with the entire administration focusing more on non-development concerns, the state capacity becomes a constant victim of circumstance— “tax and tariff collection are weak, laws are unevenly applied.”12Van de Walle, Nicolas. African Economies and the Politics of Permanent Crisis, 1979-1999. Cambridge University Press, 2001. P 55.

One could argue that the persistence of the colonial legacy of Sub-Saharan institutions is preventing the region from experiencing a more redistributive effect of social policy on social welfare at a rate commensurate to other regions in the Global South. As Claude Ake puts it, “colonialism in Africa was starkly different from the colonial experiences of the Americas, Europe, and Asia because of the colonial government’s extreme arbitrariness and tight grip on every aspect of the colonial economy.” Colonial powers redistributed lands and dictated who should grow what and how; interfered with education to ensure a predicted labor outcome; and designed infrastructures primarily to promote its extractive enterprise. 13Ake, C. (1995). Democracy and development in Africa. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. It is no surprise, therefore, that the region’s exemplary welfare regimes, Mauritius and Botswana, are nations with different historical institutional trajectories.

Unlike most of the sub-Saharan nations, Mauritius’ colonial legacy left the nation with the type of institution that enabled them to evade the distinctive patrimonial institutional trap that continues to hamstring the impact of social policy in other countries in the region. In most sub-Saharan nations, the British colonial administration “did little to develop strong, indigenously rooted institutions that could tackle the development demands of modern states.”14Brätigam, Deborah A., and Stephen Knack. “Foreign Aid, Institutions, and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Economic Development & Cultural Change, vol. 52, no. 2, Jan. 2004, pp. 255–285. Mauritius, however, was one of the exceptions to the rule. The final colonial power in control of the East African island, the British, left Mauritius with strong educational institutions, state capacity, and a robust civil service rooted in meritocratic traditions.15Ibid. Unfortunately, British colonial rule in most of the other countries in the region left post-independence political elites with extractive states and crippling civil and political societies.16Ibid.; Daron Acemoglu, et al. “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation.” The American Economic Review, vol. 91, no. 5, 2001, p. 1369 These extractive institutions have persisted, as Daron Acemoglu and others noted, because they align with the vested interest of the political elites.17Daron Acemoglu, et al. 2001.

Additionally, the alignment between early political and business classes is another factor that favors Mauritius’ expansive social policy development. Unlike other countries in the region where elite interests align with maintaining the extractive state, Mauritian elites align on a developmental agenda predicated on human capital development.18Daron Acemoglu, et al. 2001; van de Walle, Nicolas. (2009); Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2010 This broad-based class alignment, according to Marianne S. Ulriksen, is responsible for Mauritius’s universal coverage of social risks.19Ulriksen, Marianne S. “Welfare Policy Expansion in Botswana and Mauritius: Explaining the Causes of Different Welfare Regime Paths.” Comparative Political Studies, vol. 45, no. 12, Dec. 2012, pp. 1483–1509.

Similarly, Botswana’s divergent historical institutional development from the rest of the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa explains its vibrant and expansive social policy. Whereas most colonial Sub-Saharan African states are fraught with “…historical and persistent patterns of insecurity and inefficient property rights, absolutist states,” Botswana is an aberration from the norm.20Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2010. In Botswana, elite interests align with the structure of institutions both before and after colonialism.

Like Mauritius, Botswana’s historical institutional development played a crucial role in ensuring that the interest of the political elite aligned with human capital development and social insurance. In another study, for instance, Acemoglu and others note that Botswana experienced a divergent path from most African states because of their inclusive pre-colonial institutions. More importantly, Botswana’s political elite were interested in maintaining and strengthening the institution of private property.21Acemoglu, Daron, Simon H. Johnson, and James A. Robinson. “An African Success Story: Botswana, July 11, 2001 (working paper).

DATA

Data and Time Frame

To test whether the structure of public sector institutions mediates the quality of social service delivery in capitalist democracies in Sub-Saharan Africa, this research uses data from the World Bank’s World Development Index and Worldwide Governance Indicator from 2000 to 2018 as a proxy for institution structure.

Methodology and Control

The focus on democracy is a major strength of this study because this variable informs both the institutional structure and the expansion of the size of the public sector in the Global South in general and Sub-Saharan Africa in particular.22According to Harding, Robin, and David Stasavage. “What Democracy does (and Doesn’t do) for Basic Services: School Fees, School Inputs, and African Elections.” The Journal of politics 76.1 (2014): 229-45, democracies in Africa have a higher rate of school attendance than non-democracies in the region. Furthermore, Harding, Robin. “Attribution and Accountability: Voting for Roads in Ghana.” World politics 67.4 (2015): 656-89, shows the impact of electoral competition at the micro-level on the expansion of public goods. More importantly, Haggard, Stephan, and Robert R. Kaufman. 2008, find that democratic institutions have a more redistributive effect on social policy when compared with nondemocratic regimes. Therefore, controlling for this variable allows the study to investigate what, other than the nature of polity, mediates basic social welfare spending. In addition to the polity variable (in this case, democracy), research in the Global South includes other fundamental confounding variables that are all too often overlooked in advanced industrial capitalist democracies studies, such as the state-society relationship and public goods provision. In contrast to the Global North, informal institutions of welfare and the size of informal sectors contribute to the variation in social determinant outcomes in the Global South.23Ian Gough and Geoff Woods (Eds) (2004), Insecurity and Welfare Regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Because of these fundamental differences between the North and South social policy regimes, it is imperative that the study controls for some social welfare similar research design framework. Like the work of Evelyne Huber and John Stephens in Latin America, this regional framework, focusing on Sub-Saharan Africa, makes it manageable for the study to control for “relative GDP per capita, sector dualism, inflow of foreign direct investment, informal employment, IMF conditionalities, openness, education, female labor force participation, and youth population.”24Huber, Evelyne, and John D. Stephens. 2012.

Finally, the lack of pre-taxation data is another challenge in measuring the quality-of-service delivery in the Global South.25Pontusson, Jonas. 2005. ln lieu of pre-taxation data, this study leverages post-tax and cash transfer data. In doing so, the study holds constant factors other than government policy that affect absolute poverty.26Huber, Evelyne, and John D. Stephens. 2012.

Dependent and Independent Variables

As mentioned above, one can predict the quality of social welfare service delivery by observing the variation in poverty outcomes in relation to or independent of government welfare spending levels. Therefore, this study uses poverty level, specifically absolute or extreme dimension of poverty, as the dependent variable.27Poverty is a multidimensional variable, making conceptualization and measurement relatively challenging. One way to conceptualize poverty is by evaluating the standard of living of the individual on a holistic scale, namely- lack of income or asset- or on a multidimensional scale, according to Barrientos, Armando, and Miguel Nino-Zarazua. Social Assistance in Developing Countries Database Version 5.0., 2010. Another challenge with conceptualizing poverty is that this variable is a function of both wealth and income redistribution; therefore, it exists on both a relative and an absolute level, see Pontusson and Jonas. 2005. Indeed, societal perception of poverty varies both across and within communities. In addition, this study also measures extreme poverty by leveraging the international level of poverty headcount ratio $1.90 (PPP) percent population.28Measuring poverty is also a challenging ordeal. Poverty levels are sensitive to welfare measurements, see Levine, Sebastian, et al. “The Impact of Cash Transfers on Household Welfare in Namibia.” Development Southern Africa, vol. 28, no. 1, Mar. 2011, pp. 39–59.

Independent Variables

Social policy, the first independent variable in this study, is a confluence of three discrete components: education, health, and social coverage. Even more interesting is the fact that we can also break down social coverage into sub-categories: social insurance and social assistance coverage. To measure these sub-divisions of social coverage, the study uses the World Bank’s “coverage of social insurance programs” (% of population) and “coverage of social safety net programs” (% of population) as measures for social insurance and social assistance, respectively.29ASPIRE: The Atlas of Social Protection – Indicators of Resilience and Equity, The World Bank. The data are based on national representative household surveys. (datatopics.worldbank.org/aspire/).

Like social coverage, education spending can be subdivided into primary and secondary school expenditures. Primary school expenditure is measured as “current education expenditure, primary” (% of total expenditure in primary public institutions), while secondary school expenditure is measured as “current education expenditure, secondary” (% of total expenditure in secondary public institutions).

In addition to social coverage and education, health spending is another independent variable in this study. The research uses current health expenditure per GDP as its measure.

The tentative hypothesis of this study is that each of these social determinants of human capital variables— health, education, and social coverage– would have a negative statistical significance on poverty. Meaning, they will likely alleviate poverty. According to Huber and Stephen, a confluence of social spending, investment in education, and health spending in the context of a democracy alleviates absolute poverty.30Huber, Evelyne, and John D. Stephens. 2012. Thus, one predicts that Sub-Saharan African democracies would experience a similar outcome.

Last, but certainly not least, the final independent variable is the institutional structure.31For more on the challenges of measuring institutions, see Birdsall, Nancy. “Do No Harm: Aid, Weak Institutions, and the Missing Middle in Africa.” Development Policy Review, vol. 25, no. 5, Sept. 2007, pp. 575–598. Like poverty, measuring and conceptualizing institutions is complex. As Nancy Birdsall puts it, none of the current measures of institutions capture the full extent of a country’s institutional power. Using the worldwide governance indicator as a proxy for institutional structure, this research makes two fundamental assumptions: (1) institution structure is a part of the governance indication; (2) of the six dimensions of governance indicators, government effectiveness (“GE”) and corruption control (“CC”) are the two fundamental variables that exemplify the structure of public sector institutions.32Kaufmann, Daniel, et al. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, vol. 3, no. 2, Sept. 2011, pp. 220–246. In some ways, CC and GE serve as the best indicators of institutional strength because they capture both the quality of service and the connection between input and output. For Sub-Saharan Africa, the tentative hypothesis is that CC and GE would likely inform poverty levels. In other words, these variables would have a statistically significant negative impact on poverty levels. Countries with weak institutional guardrails, specifically in the areas of corruption control and government effectiveness, will likely experience higher levels of poverty regardless of government social policy spending.

RESULTS

Regression Analysis

To test our hypotheses for the likelihood of social welfare spending and institutional structure alleviating or exacerbating poverty levels, the research uses a linear regression model. First, the study tests the likelihood of the structure of institutions, particularly government effectiveness (GE) and control for corruption (CC), increasing or alleviating poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, independent of the social policy interventions. Secondly, the research repeated the same procedure to also test the likelihood of each of the social policy variables alleviating or increasing poverty.

Findings

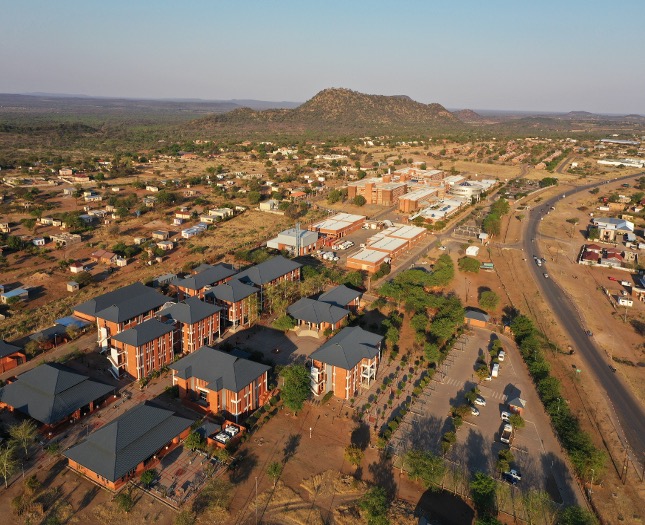

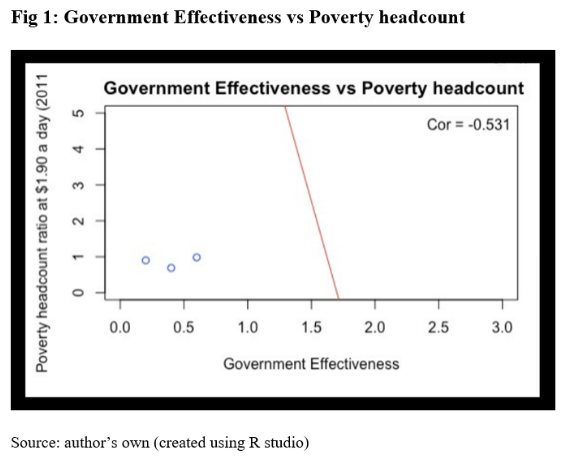

Based on Fig 1, the correlation coefficient for government effectiveness (GE) is significant. From the regression model, we can deduce that GE is likely to alleviate poverty, which agrees with the study’s working hypothesis for the institutional structure variable. Thus, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that a significant linear relationship exists between government effectiveness and poverty alleviation. In other words, Sub-Saharan countries are more likely to achieve their poverty reduction goals by improving their quality of governance.33For more on quality of governance and human capital development, see Rothstein, Bo. The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective. University of Chicago Press, 2011. Nonetheless, more research must be done to explain the causal mechanism, specifically pinpointing how strengthening government effectiveness results in poverty reduction.

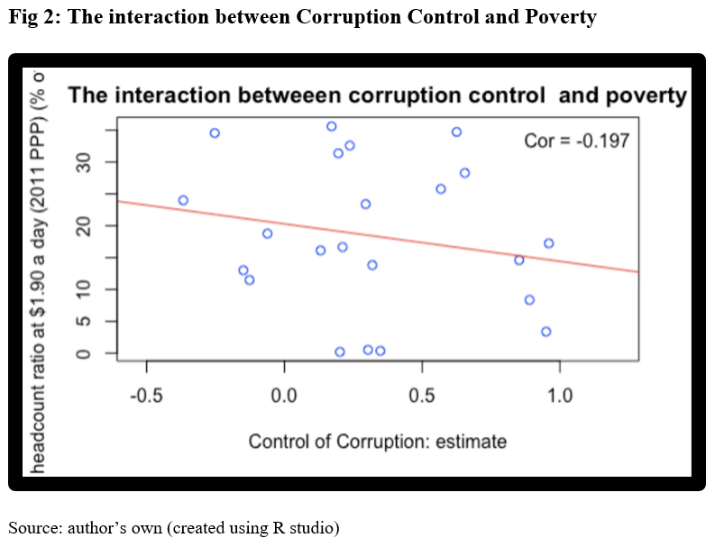

In Fig 2, control for corruption (CC), the other structural variable examined in this study, has a correlation coefficient that is not significant. Thus, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that a significant linear relationship exists between control for corruption and poverty alleviation in Sub-Saharan Africa. One reason for inconclusive findings might be the problem of sparseness of data. As we already know, the reliability of this linear model is also contingent on the data sample size. Moreover, the paucity of data from consecutive years makes it difficult to calculate the lagging effect of each of these structural variables. For instance, it is more likely that a nation would experience the redistributive effect of corruption control two to three years after implementing a corruption control policy, not immediately after. However, from the data, most of these countries have a data gap of five to seven years for some of these indicators, making it difficult to compute the lagging effect of these variables on poverty reduction.

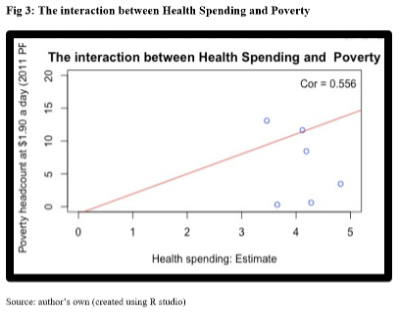

Like the control for corruption variable, most social policy variables, except healthcare spending (Fig 3), have insignificant correlation coefficients. In this regard, the evidence is insufficient to conclude that these social policy variables have a linear relationship with poverty alleviation. Despite these inconclusive education and social insurance spending findings, their linear regression models show a positive correlation between their unique intervention and poverty alleviation.34It is important to note that primary school spending on education (Fig 8), though not statistically significant, has a promising negative linear relationship with poverty levels. Yet health spending, Fig 3, surprisingly has a positive statistically significant correlation with poverty. In contrast to the tentative hypothesis of this study, Sub-Saharan countries are more likely to see a rise in poverty levels when healthcare spending increases.

A context-based historical analysis of the countries within the case selection might explain the positive correlation between health spending and poverty levels. Here, we can see that an external shock, specifically the rampant HIV and AIDS epidemic in the 1990s and early-2000s, might account for why Sub-Saharan Africa saw an increase in poverty levels even as healthcare spending increased.35See Simms C. Sub-Saharan Africa’s HIV pandemic. Am Psychol. 2014;69(1):94-95, for more on the HIV pandemic. During this period, most of the countries in this study, which are in the Southern Africa region, experienced a significant drop in household income because a major percentage of their working population contracted HIV and AIDS.36Sharp C, Venta A, Marais L, Skinner D, Lenka M, Serekoane J. First evaluation of a population-based screen to detect emotional-behavior disorders in orphaned children in Sub-Saharan africa. AIDS and behavior. 2014;18(6):1174-1185. With many of the governments in these countries initially in denial of the gravitas of the HIV epidemic, breadwinners and income providers with HIV were deprived of the urgent care they needed to cope with the virus, resulting in them becoming severely sick and exiting the workforce altogether. As a result of this massive labor force exodus, poverty levels skyrocketed during this period, even as government spending on healthcare, both preventive and palliative care, increased.37See Buvé A, Bishikwabo-Nsarhaza K, Mutangadura G. The spread and effect of HIV-1 infection in Sub-Saharan africa. The Lancet (British edition). 2002;359(9322):2011-2017.

CONCLUSION

Literature on social policy in the Global South, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, is incomplete without factoring—using quantitative evidence—how the institutions that emerged from indirect colonial rule mediate the quality of social service delivery.

Through historical analysis, we can see that Mauritius and Botswana are not quintessential examples of the Sub-Saharan Africa story. Unlike most of the Sub-Saharan nations, Mauritius’ colonial legacy left the country with the type of institution that enabled them to evade the distinctive patrimonial institutional trap that continues to hamstring the redistributive effect of social policy in other countries in the region. More specifically, Mauritius inherited better educational and civil service institutions from the British, and Botswana inherited a well-established system of property rights from their colonial power.

Whereas historical analysis is fundamental to paint a context-based picture of the impact of corruption and rule-bending in mediating the redistributive effect of social welfare interventions, a quantitative method is essential in testing the likelihood of these public institutions mediating the quality of social welfare service provision.

These studies set the stage for potential research on the causal mechanism, specifically illustrating how the structure of institutions mediates the redistribution of social welfare provisions. Moreover, it empowers researchers to test if there is a specific government social spending threshold where the impact of the institution’s structure is negligible.

Thus, using seven Sub-Saharan African democracies as case studies, the report leverages a regression model to test the likelihood of colonial institutional structures mediating the quality of social services delivery. It concludes that sufficient evidence suggests a significant linear relationship exists between government effectiveness, one of the structural variables, and poverty alleviation. However, the study finds no evidence to conclude that education and social coverage spending have a linear relationship with poverty alleviation. Although we cannot draw significant conclusions from social policy results, it is the hope that this study will spark a much-needed debate on the impact of Sub-Saharan African institutional structure on social welfare service delivery and social determinant outcomes.

In addition to this audacious goal, another intention is to create more awareness of the limitations that come with doing quantitative research in the region, specifically the sparseness of data. Data sparseness and measurement constraints make quantitative cross-national studies challenging, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. In future research, the aim is to circumvent these challenges by focusing on subnational studies and pair comparisons.

Foreign Policy and Diaspora Studies Lab (FPDS-LAB)

About the ACSTRAP Foreign Policy and Diaspora Studies Lab

This report was prepared by Pandit Mami of the Africa Center for Strategy & Policy’s Foreign Policy and Diaspora Studies Lab. Our research on African Foreign Policy and diaspora studies focuses on regional and international affairs, particularly the implications of great power competition in Africa. The lab looks at institutional policies at the level of the African Union and the relations among African states and the international community.

About the Authors/Lab Contributors

Pandit Mami: Research Lead and Analyst

Pandit Mami has 13+ years of experience in promoting inclusive economic growth and youth development by leveraging impact-led design, transformative justice, and collective action strategies across the globe, including Sierra Leone, Vietnam, Singapore, the U.S. (Detroit & Milwaukee), and Israel. His interests center on the condition under which the Public-Private Partnerships improve the quality of social welfare services delivery and promote upward mobility for folks on the wrong side of public good provisions.