Africa Rising: Four Macroeconomic Factors to Consider in Sub-saharan Africa

Dr. Moon Oulatta, Expert Consultant, African Political Economy, USA

moulatta@africacfsp.org

The Economist described the African continent as a “hopeless continent’’ back in May 2000. This impulsive supposition was mainly driven by a tank of factual evidence comprising weak institutional capacities, calamitous growth performance, and unending political instability. While economic growth remains extremely frail and unstable, partially due to weak and volatile commodity prices, there is now increasing empirical evidence advocating the view that Sub-Saharan African countries are currently making substantial improvements in key areas. In fact, following a reassessment back in December of 2011, The Economist corroborated this view in an article titled “Africa rising”. Ultimately, openness and macroeconomic stability have been instrumental in explaining Sub-Saharan Africa’s recent economic progress.

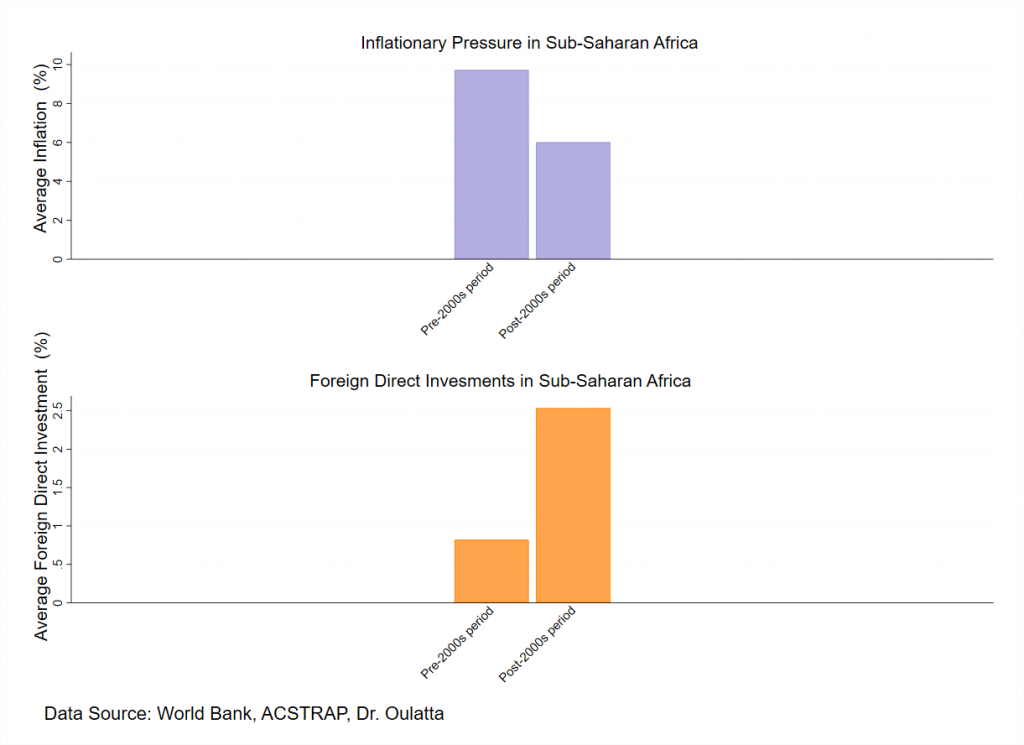

I. Price stability has significantly improved in the last decade

This has come as the result of key monetary policy reforms. For example, in the last couple years, some central banks in ECOWAS, EAC, and SADC have adopted inflation targeting (IT) and monetary aggregate targeting (MOT) as the leading monetary policy frameworks.1International Monetary Fund (2018). “Annual report on exchange arrangements and exchange restrictions.” International Monetary Fund. Prior to entering the third millennium, inflationary pressures in Sub-Saharan African were largely driven by the members of SADC, mainly due to intense civil conflicts, strong discretionary spending, and a stronger nominal rate of depreciation against the dollar.

Figure 1: Business Confidence and Price Stability in Sub-Saharan Africa

However, in the last decade, the average inflation rate in the SADC zone has significantly declined. Overall, the implementation of IT has led to a significant decrease in average inflation in Sub-Saharan Africa and subsequently large increases in foreign direct investments; notably in the CEMAC and ECOWAS zones. Robust foreign capital inflows in Central Africa (CEMAC) and West Africa (ECOWAS) has mainly been influenced by lower inflationary pressures, stronger political stability, and a relatively lower nominal rate of depreciation against the dollar.

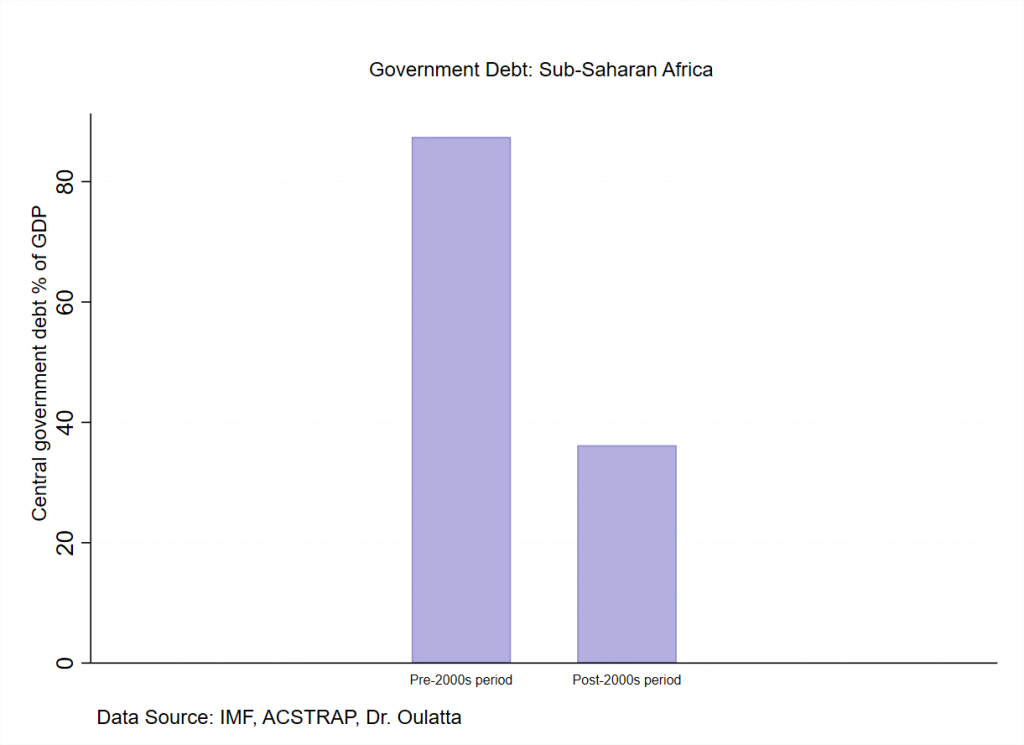

II. Debt management has significantly improved

Although most African countries remain heavily indebted, debt management has significantly improved in last decade. This has come as a result of significant improvements in fiscal sustainability, mainly catalyzed by a progressive reduction in deficit financing, diversifying the tax base, and a gradual reduction in tax evasion. Furthermore, the addition of debt relief programs implemented by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank has led to a significant reduction in debt service and in the overall level of debt in Sub-Saharan Africa.2International Monetary Fund (2016). “Heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) initiative and multilateral debt relief initiative (MDRI)-statistical update”. IMF Staff Report. While concerns about Africa’s debt remain viable, mostly exacerbated by the prospect of weak tax revenues emanating from exports, Figure 2 shows that the level of debt is becoming sustainable.

Figure 2: The Evolution of the Debt Stock in Sub-Saharan Africa

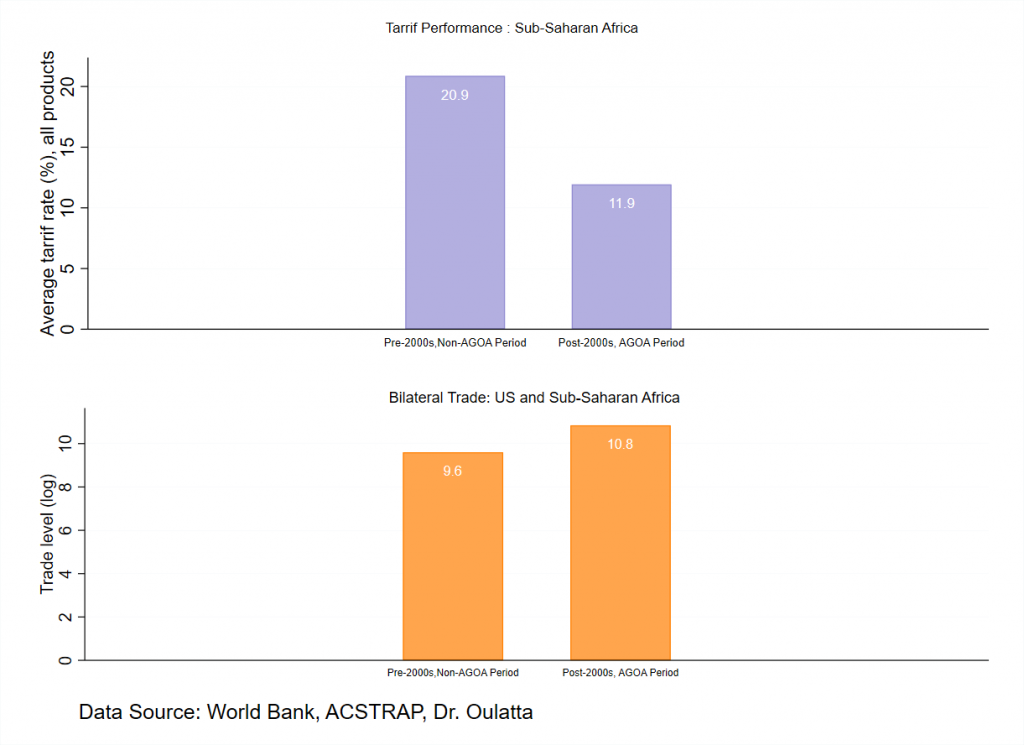

III. Trade Performance: The implementation of the African Growth Opportunity Act (AGOA)

The AGOA act was signed by President Clinton in May 2000 and it was prolonged by presidents Bush and Obama. The implementation of AGOA has led to a significant reduction in average tariffs on all products, which has resulted in significant improvement in USA-Africa bilateral trade relations. By 2008, the program added 1,800 products to the list of duty-free products that were included in the previous Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program—an initiative aimed at expanding trade between the United States and the developing world. Ultimately, AGOA has been instrumental in boosting U.S—Africa trade.

Figure 3: Bilateral Trade Performance (US and Sub-Saharan Africa)

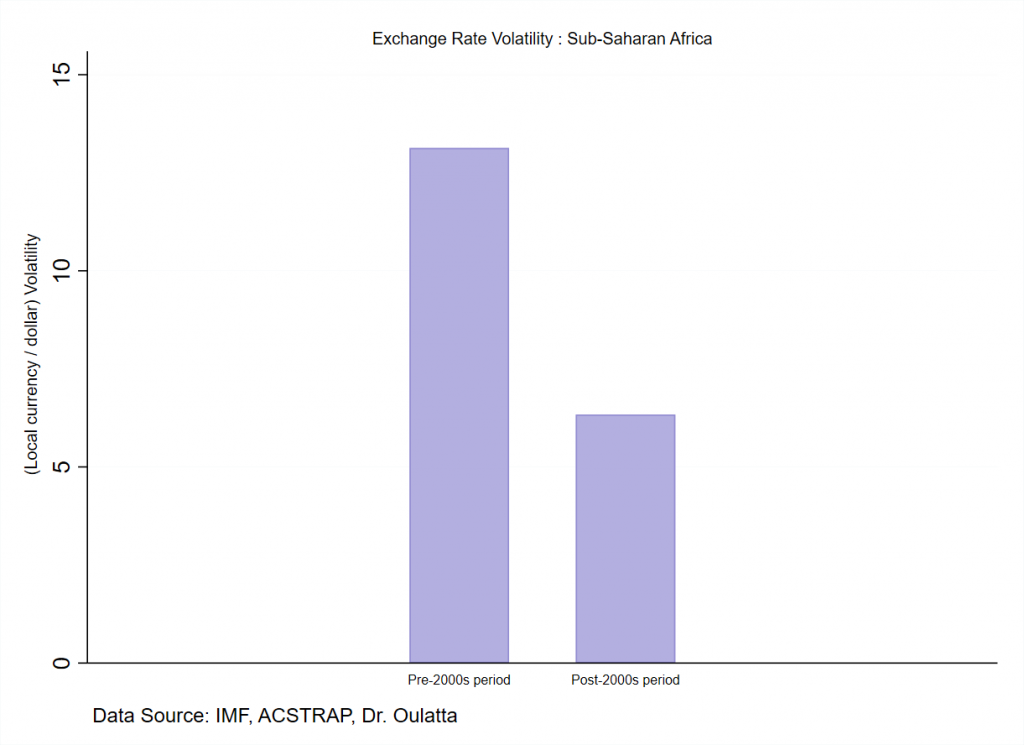

IV. Increased stability in the price of international trade (local currencies against the dollar)

Exchange rate volatility has significantly declined, mainly due to concrete exchange rate reforms enacted by many African central banks, particularly those central banks located in the highly fragile Sub-Saharan African regions. For example, Zimbabwe adopted the dollar as the legal tender as means to improve credibility and remove the option of discretion. Eritrea, Djibouti, and South Sudan are now using the dollar as a nominal anchor [1]. On average, these exchange rate reforms have led to a gradual reduction in exchange rate volatility across Sub-Sharan Africa.

Figure 4: Exchange Rate Volatility in Sub-Saharan Africa

CHALLENGES & THE WAY FORWARD

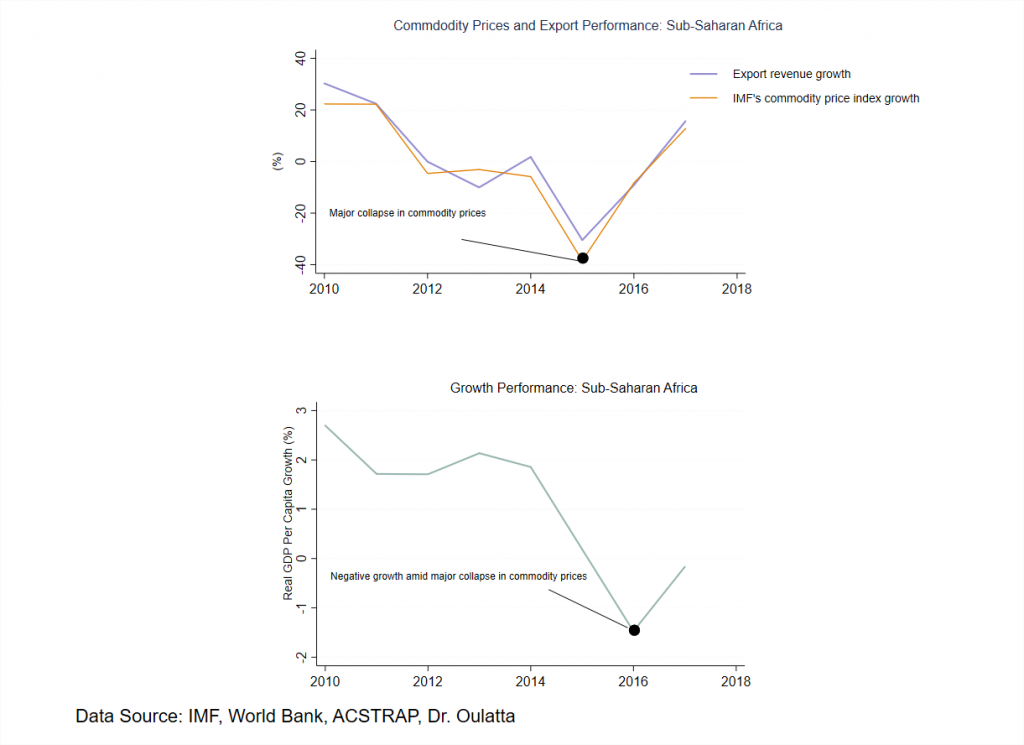

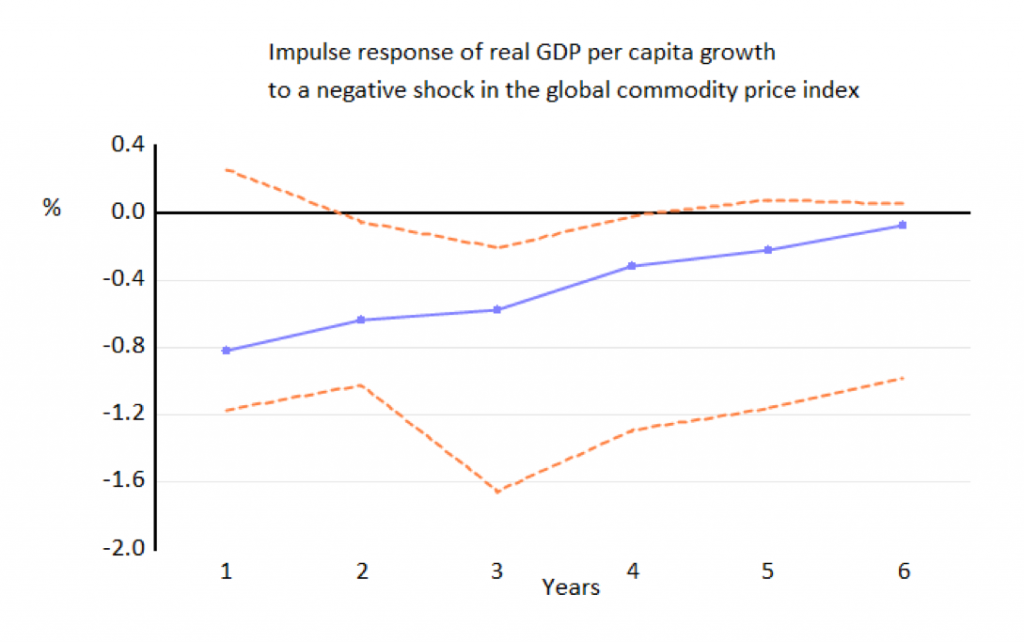

In 2015, the drastic collapse in commodity prices caused a catastrophic decline in export revenue and subsequently poor growth performance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Using aggregate data obtained from the World Bank, Figure 5 examines the impact of a negative shock in the IMF’s global commodity price index on Sub-Saharan Africa’s growth performance. This is achieved by using the sign restrictions approach to identify the key shocks in a structural vector autoregression (VAR) model. The response of economic growth to a collapse in the global commodity price index convey two important messages. Firstly, negative commodity price shocks reduce Sub-Saharan Africa’s growth rate, but the effect is more significant in the second year following the impact of the shock. Secondly, commodity price shocks have lasting depressing effects on economic growth; it takes roughly four years for growth performance to revert to normal. This finding corroborates the view that terms of trade shocks have a lasting effect on economic growth in developing countries.

Figure 4: Growth Performance

Extreme vulnerability from commodity price shocks stems from the fact that Sub-Saharan African countries remain largely agriculturally based. This condition makes them highly vulnerable to commodity price shocks, because exports are less diversified and mostly driven by minerals and cash crops, whose prices are exogenously determined on the world stage. The lasting effects of commodity prices shocks on economic growth reiterates the need to diversify the economic locomotive of Sub-Saharan African economies; this must be a top priority in the agenda of African policy makers. Poor growth performance is also endogenously driven by other factors such as high youth unemployment, mediocre regional investments in infrastructure, and in educational opportunities. These issues are mainly due to lack of fiscal coordination and manufacturing at the regional level. Diversifying exports and accommodating the financial needs of local businesses would be instrumental in mitigating exposure to terms of trade shocks and global financial crises.

Figure 5: SVAR MODEL (Sign Restrictions)