Backgrounder

The Risk of Islamic Insurgency in Senegal: A Foreboding History

Dr. Robin Hardy, Senior Vice President of Global Research and Policy Development

rhardy@africacfsp.org

Introduction

For almost fifteen years, terrorism has raged across the Western Sahel. Tens of thousands of lives have been lost, property has been destroyed, and thousands of individuals have been displaced. Yet throughout this time Senegal has been known as a beacon for stability, “untouched” by the violence afflicting its neighbors. Yet if the country has a reputation as a moderate political state that has avoided the region’s wave of extremism, this is smoke and mirrors. Senegal is not as stable as it appears. This analysis will reveal that embers of Islamic militancy not only smolder today, but are reminiscent of an important characteristic of Senegal’s history—risking explosion at any time.

Western Sahelian Terror since 2009 – and current risk to Senegal

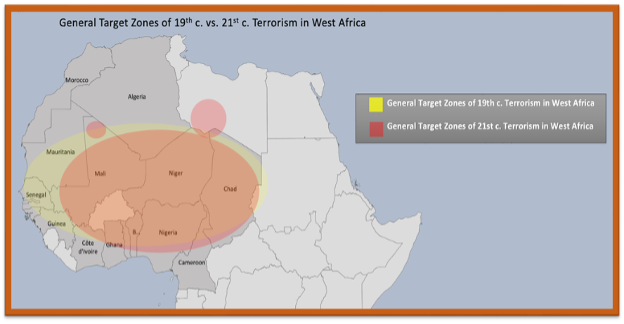

From 2009 jihād exploded in the Western Sahel with its epicenter in northeast Nigeria. Since then, Islamic radicalism has spread throughout the region, most notably to Ivory Coast, Mali, Guinea, Niger, Chad, Mauritania, Cameroon, and Burkina Faso. 1Robin Hardy, “Countering Violent Extremism in Sub-Saharan Africa: What Policy Makers Need to Know”. World Affairs: v. 182 i. 3, 2019; Atta Barkindo, “The Sahel: A New Theater for Global Jihadist Groups?.” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, Vol. 12, No.2, March 2020 (21-26); Elodie Toto, Foreign Policy, June 14, 2023. Throughout this time analysts lauded the stability of Senegal where it was believed that terrorism was unlikely to take hold given its moderate Sufism combined with a strong-handed, if not semi-despotic, political authority.2Hardy, “Countering Violent Extremism in Sub-Saharan Africa,” 262-263. Toto, Foreign Policy, June 14, 2023. Toto recently argues that the reluctance of President Macky Sall to leave office after two terms (his earlier-stated commitment to Senegal’s citizens) is making Senegal more vulnerable to Islamic destabilization. But matters were not as they seemed. As of this writing it is clear that jihadist elements have been brewing in Senegal with a real potential for lethal detonation.

Beginning in 2015-2016 a smattering of arrests, prosecutions, and prison sentences reveal the existence of extremist elements in Senegal. Individuals linked to Boko Haram, al-Qaeda, and ISIS have been active in Senegal, some of whom were trained and engaged in deadly acts in the Ivory Coast, Nigeria, and Libya.3Ryan Cummings, “Senegal, ISIS, and al-Qaeda: A Terrorism Trifecta”. Global Challenges Counter-Extremism. Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, June 6, 2017. Senegal’s porous borders with Mali and Guinea are at greatest risk. Violence has already spread to the Senegalese towns of Tambacounda and Kédougou, suggesting the country has not escaped the Sahel’s larger trajectory of violence.4Paulin Maurice Toupane, “Preventing Violent Extremism in South-eastern Senegal.” Institute for Security Studies, December 16, 2021.

AQIM or al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s Mali branch has expressed its intent to conduct attacks in the Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, and Senegal. Moreover, the expansion of Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM)—especially the Macina Liberation Front—now means an increased ability to attack eastern Senegal. Leaders of both groups are resolved to extend presence to the entire West African littoral. A key motivation is to rid the Western Sahel of extra-African presence, particularly peacekeeping and international counter-terrorism missions.5Rahma Bayrakdar, “Al Qaeda’s Growing Threat to Senegal.” Critical Threats, February 18, 2021. https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/al-qaedas-growing-threat-to-senegal. As example of this momentum, scores of fatalities in late July 2022 were the result of Islamist attacks and Malian counter-terrorist operations (first outside of Bamako, and then in Sokolo, Kalumba, and Mopt). The Katiba Macina branch of al-Qaeda launched the violence, condemning Mali for allowing Russian “mercenaries” (Wagner Group) to assist the military in Mali.6No signature, “Al-Qaida’s Affiliate Claims Attack on Mali’s Main Military Base”. Extremism Watch, Reuters, July 23, 2022; Jorge Engels, “Mali Military Says 15 Soldiers, Three Civilians Killed in Separate ‘Terrorist’ Attacks.” CNN, July 28,2022. https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/28/africa/mali-terrorist-attack-casualties-intl/index.html; Fadimata Kontao, “Militants Attack Mali’s Main Military Base.” Reuters, July 22, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/heavy-gunfire-heard-main-mali-military-base-2022-07-22/ Indeed, first in 2013 thousands of UN peacekeepers were deployed to Mali (MINUSMA)—followed in 2021 by Russia’s Wagner Group under the guise of assisting Mali’s government in CVE operations (Wagner had maintained presence in Africa since at least 2017, most notably in Libya and the CAR. Despite a recent coup in Russia and the subsequent death of Wagner’s leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, Vladimir Putin has expressed a renewed commitment to remain in Africa).7Edward McAllister, “Explainer – Why Mali is Kicking Out US Peacekeepers,” Reuters, June 30, 2023. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/explainer-why-mali-is-kicking-out-u-n-peacekeepers/ar-AA1dg1wY?ocid=msedgdhp&pc=U531&cvid=969008be9f0640799334f5eed2cd6aad&ei=308; Jason Burke, ‘It is like a virus that spreads’: Business as Usual for Wagner’s Extensive Africa Network, The Guardian, July 6, 2023. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/it-is-like-a-virus-that-spreads-business-as-usual-for-wagner-group-s-extensive-africa-network/ar-AA1dvubB?ocid=msedgdhp&pc=U531&cvid=325e03bfe90844909df60a9a982eafd8&ei=233; James Stavridis, “Putin and Wagner Are Still Gunning for Africa,” Bloomberg, August 1, 2023.

The risk of transnational terror notwithstanding, internal pressures in Senegal are equally as volatile. Extremist ideology presents a risk that is potentially more difficult to control than external actors.8Cummings, “Senegal, ISIS, and al-Qaeda: A Terrorism Trifecta”. 2019-2020 have thus far been the most challenging. First in 2019: an elicit purchase of 12mm ammunition; a separate state seizure of AK-47 cartridges; as well as a prosecution of a legislator who sold false currency that totaled at least $50 Million (USD) all came before Senegal’s court.9Cummings, “Senegal, ISIS, and al-Qaeda: A Terrorism Trifecta”; No signature, “Country Reports on Terrorism 2020: Senegal.” Bureau of Counter-terrorism, U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2020/senegal/ Then in 2020 Senegal’s intelligence was alerted to several individuals who were suspected to be linked to terrorism, including: a French national of Senegalese descent accused of leaving the country to fight for the Islamic State; a Senegalese who was accused of plotting to kill his father who later admitted to traveling to Libya where he joined and trained with a jihadist organization; a Senegalese who was accused of planning to blow up a French restaurant in the capital to avenge images of the prophet Mohammed in France; and a German who was stopped in transit on suspicion of being a terrorist.10No signature, “Country Reports on Terrorism 2020: Senegal

Responding to both internal and external threats, Senegal’s leaders have engaged in a multi-pronged approach by setting up military bases on the eastern border; training police to detect and deter terrorists in-country; contributing forces to MINUSMA (now scheduled to exit the Mali theater by the end of 2023); and participating in counter-terrorist programs with ECOWAS, AU, the EU and with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). With the goal of further enhancing the country’s counter-terrorism strategy an Inter-Ministerial Coordination Framework for Counter-terrorism Operations (CICO) partnered with the UNODC at a joint conference in May of 2022 (following an initial meeting in 2016).11Cummings, “Senegal, ISIS, and al-Qaeda: A Terrorism Trifecta”; No signature, “UNODC Supports Senegalese authorities in the development of their national counter-terrorism strategy.” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2022; No signature, “Country Reports on Terrorism 2020: Senegal.”

Accurately assessing the challenges that face Senegal, however, goes beyond the recent headlines. Policymakers need to understand the country’s deep history with religious radicalism in order to adequately understand the current risks. To be sure, religious extremism is not a new phenomenon in Senegal. Jihadism has deep roots in and around the country where historically fighters maintained extensive breadth and reach, controlling much of the population.

Age Old Militant Islamism as Pretext for Contemporary Unrest

We must recall that the borders of modern Senegal are a fiction of the French imperial administration. Senegal of yesterday was thus much larger than its contemporary boundaries. At its greatest breadth in the late nineteenth century, Senegal extended across much of West Africa, including the modern states of Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, and Mauritania.12See Marcel Olivier, Le Sénégal (Paris: E. LaRose, 1907); David Robinson, Paths of Accommodation: Muslim Societies and French Colonial Authorities in Senegal and Mauritania (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2000); and Boubacar Barry, La Sénégambie du XVéme au XIXéme siècle (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1985 An important tradition of Islamic militancy can only therefore be properly analyzed against the backdrop of “greater” French Senegal during the high-colonial period.

From the 1850s French conquest of Senegal’s hinterland was extensive. Invasion meant that Europeans encountered jihâd. Before the eighteenth century jihâd was invoked between African groupings, but with increased European merchant naval presence African Muslims were no longer content with spreading Islam to locals; jihadist activity now included resisting the European purchase of slaves at Atlantic ports as well as militarily agitation against the growing number of Europeans in the African interior. Muslim jihadism was effective to unite competing tribal communities against this exogenous threat. In fact Islam grew among West Africans in the era as a response to the French movement to invade and rule Senegal’s backcountry.13See Christopher Harrison, France and Islam in West Africa, 1860-1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); Robinson, The Holy War of Umar Tal, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985); Martin Klein, Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Barry, La Sénégambie du XVéme au XIXéme siècle; Marcel Olivier, Le Sénégal (Paris: E. LaRose, 1907); David Robinson, Paths of Accommodation: Muslim Societies and French Colonial Authorities in Senegal and Mauritania (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2000); and Boubacar Barry, La Sénégambie du XVéme au XIXéme siècle (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1985). For more on the variational nuances of jihād, see Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1974), 75, 269, 292, 515; and John Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

One of the most feared Muslim fighters in “greater” Senegal at the time was the Fulbe, El Hajj Umar Tal. From the Futa Toro, Tal studied Islam in the high country of the Futa Jallon and even journeyed to Mecca. Tal launched a West African Islamic empire across the region between 1852 and 1864. Once a prosperous trade region, by the eighteenth century the Sahelian trans-Saharan caravan economy had been decimated by European commerce at the Atlantic. Moors, on the northern banks of the Senegal River, benefited from trade with Europeans but this was not the case for Umar Tal’s countrymen farther in the interior. Tal thus led a jihād not only to institute strict Islamic rule over West Africans, but also to repel or at least control European trade in the West African backcountry. Tal’s onslaught turned into territorial and material annexation of large swaths of “greater Senegal” by way of raids, carnage, enslavement, and environmental destruction. At its height during the late 1850s and early 1860s, Tal’s Tukolor Empire covered a massive territory including the modern territories of upper Senegal, Guinea and most of Mali. 14See J. Spencer Trimingham, A History of Islam in West Africa (New York, Oxford University Press, 1959); Philip Curtin, “Jihad in West Africa: Early Phases and Inter-Relations in Mauritania and Senegal,” The Journal of African History 12, No 1 (1971): 11-24; David Robinson, The Holy War of Umar Tall: The Western Sudan in the mid-Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985); Eugène Mage, Voyage dans le Soudan occidental, Rev. ed. (Paris: Hachette, 1971); Philip Curtin, “Jihad in West Africa: Early Phases and Inter-Relations in Mauritania and Senegal,” The Journal of African History 12, No 1 (1971): 11-24; and Barnett Singer, “A New Model Imperialist in French West Africa,” The Historian 56, No 1 (Autumn, 1993): 69-86. Given French interest in the hinterland, Umarians and the French eventually went to war. Violent battles between 1857 and the early 1860s ended with a truce between the combatants which amounted to free trade status: the French to control the lower Senegal River Valley while Tal’s authority remained in the eastern interior.15For more on El Hajj Umar Tal’s campaigns with the French and his ultimate death in 1864, see Robinson, The Holy War of Umar Tall, especially chapters 7-9.

The Umarian movement took center stage, but Tal was not the only jihadist combining religion, economics, and politics across the region. Samori Touré, the leader of the Mandinka Empire to the south of Dakar (Guinea) from the 1870s and Mahmadou Lamine in upper Senegal from the mid-1880s, in their own way, wreaked havoc in the name of Islam. The fact that Atlantic Trade was at its height during the 1700s meant that by the nineteenth century Sahelian societies were wracked with religious, political, and commercial instability. Again here therefore, Islamic militancy was about competition over business with Europeans and responding to a blight on African communities caused by slave-raiding in the interior. If the presence of European capital and Western customs had massively destabilized traditional African lifeways, African hinterland micro wars were thus commonplace during the 1800s.16See Trimingham, A History of Islam in West Africa. Jihadist activity was about reestablishing stasis by way of controlling European trade and inhibiting the “corrupting” effects of Western culture.

Synthesis

If the contemporary risk of Islamic terrorism in Senegal should be no surprise given the country’s history, two general motivational factors stand out across time: a wish to repel threats by an ever-encroaching foreign force accompanied by a desire among Islamists to return to tradition. As was shown, the primary goal of “greater” Senegal’s jihadists in the past was to reestablish order to communities that had witnessed the destruction of slave raiding, the arrival of Western mores, and the emergence of new African elites (who had benefited from doing business with Europeans). It is not coincidental that one of the most aggressive jihadists in “greater” Senegal, Umar Tal, was from the highly religious but unprivileged nomadic Fulani herdsmen class which had not benefited from Atlantic shore trading. The scholar- jihadist thus employed a holy war to combat the French as well as to repel what he viewed as political, economic, and religious excesses among fellow West Africans.17See Robinson, The Holy War of Umar Tall. In other words, jihād was a way to reinforce conservative Islam and resist foreigners and their influence, while leveling the playing field with other Africans.

Across time economic and political mayhem is evident in territories where Islamic militancy takes hold. Today, al-Qaeda and ISIS are most active in the region where economic disadvantage is rife. Attacks against Africans and foreigners thus include Islamic reform within areas of conquest. An expansion of foreign mores today has once again destabilized African lifeways by overwhelming traditional West African political, economic and religious systems. While difference exists between the two periods, the links between religious extremist violence as a result of outside influence are remarkably similar. Jihād in the past as much as today concerns reestablishing traditional Sahelian stability in territories that have been overwhelmed by foreign influence.

Economic engagement with non-Africans and the onslaught of foreign culture have thus once again destabilized “greater” Senegal, and the response by Muslim militants—through the years—has been to install an Islamic autocractic theocracy. The blending of religion and politics characteristic of an Islamist state has been the intention for jihadists across the ages. From the prominent Umarians to al-Qaeda and ISIS, aggressive outsiders and a concomitant economic and social disruption can only be combated with establishing conservative Islamic rule. In this way, Tal argued that jihād was just as important against wayward Muslims as it was against invading European Christians. There is an age old defense for Muslims to wage a holy war against impious Muslims as well as unbelievers. Critically, this is not a conflict between ethnicities, but a violent campaign targeting those whose culture does not align with the Sharī‘a.18Nikki R. Keddie, “The Revolt of Islam,1700 to 1993: Comparative Considerations and Relations to Imperialism.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 36, No. 3 (1994): 463-487; Jamil Abun-Nasr, “Some aspects of the Umari branch of Tijaniyya,” The Journal of African History 3, No. 2 (1962): 329-331. Jihadists therefore see themselves as defenders who are saving the population from an exogenous threat and returning the people to pure Islam.

No doubt, Islamic militancy in Senegal and its borderlands is complex. However, religious militancy in the region has been – throughout time – a direct confrontation to the onslaught of foreign influence. This was first evident during the French invasion of West Africa, only recently re-appearing when outsiders and their mores again came in contact with Sahelian communities in the interior. The motivations of Al-Qaeda and ISIS of the Western Sahel today are thus surprisingly akin to jihadist impulses of the past. The historical trajectory reveals that “greater” Senegal jihadism is an age-old result of local instability that has been brought on by external economic, technological, military or cultural invasion—responded to by a movement for the reassertion of religious conservatism. Indeed, there are key links that exist between the past and present that must not be overlooked and which require more serious attention.