The Weaponization of Famine is a Losing Game in Tigray

Cole Baker, Research Fellow, Resource, Environment & Energy Policy Lab

cbaker@africacfsp.org

This article explores the tactical and strategic incentives and disincentives for the use of famine in the ethnic conflict in Tigray, Ethiopia. Historically, Tigray has been a case study for how the intentional use of famine leads to increased instability and the revolt of an individual ethnic group against the central government. After examining the historical context and the modern-day political intricacies that ultimately led to the recent Tigray ethnic conflict, this article examines the tactical incentives and strategic repercussions of the use of famine by the Ethiopian federal government in the Tigray conflict—ultimately illustrating the consequences of the use of famine as a weapon of war in Tigray.

Tensions between Ethiopia’s federal government and the leadership of the Tigrayan ethnic group in northern Ethiopia erupted into outright conflict in early November 2020.1Michelle Gavin. The Conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region: What to Know, (Council on Foreign Relations, February 10, 2021). www.cfr.org/in-brief/conflict-ethiopias-tigray-region-what-know (Feb. 23, 2021) While Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared victory in late November, reports of ongoing violence, human rights violations, and famine in the region continue to emerge. Communication blackouts and lack of media access have prevented the international community from assessing the full humanitarian needs of the Tigray region. Nonetheless, the limited assessments which have emerged paint a grimmer picture than that being broadcast by the Ethiopian federal government. These reporting discrepancies have given rise to fears that the Ethiopian federal government is cultivating ambiguity and preventing aid relief—if not actively weaponizing famine—to consolidate power. If true, this indicates not only a supreme moral failing, but a fatally flawed cost-benefit analysis as well. While there may be tactical incentives to preventing aid from reaching the region in the context of winning the conflict, there are far greater strategic incentives for the federal government to prevent regional famine.

The use of famine as a tactic in war is a major human rights violation and against every humanitarian imperative. However, policy often stems from end goals rather than moral dictates, especially when actors engage in utilitarian morality, which allows interim evil for the sake of achieving a ‘greater good’. It is thus pertinent to examine the Tigray conflict purely from a cost-benefit analysis—entirely separate from morality—to demonstrate that the weaponization of famine in Tigray is still strategically detrimental to Ethiopia as a whole.

Historical Context

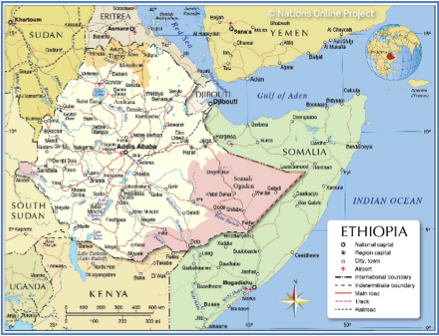

Modern Ethiopia is the product of conquests led by Emperor Menelik II in the late 19th Century, which expanded a state centered in the northern highlands into adjoining areas, primarily to the south.2Thomas Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, “The Reign of Menelik II, 1889-1913,” in Ethiopia: A Country Study, (Country Studies, Library of Congress, 1991). http://countrystudies.us/ethiopia/ (Feb. 19, 2021) The current Ethiopian state comprises over eighty ethnic groups speaking more than 70 languages. The culturally and politically dominant ethnicities of the northern highlands are the Tigray and the Amhara. While the Tigrayans only constitute roughly 7 percent of Ethiopia’s population, the Amhara are the second largest ethnic group in the country, at almost 28 percent of the population, and are the traditional ethnicity of Ethiopia’s royal family. In contrast, the south is dominated by the Oromo, which is the largest ethnic group in the country, constituting almost 35 percent of the Ethiopian population.3“People and Society” in Ethiopia, (The World Factbook, CIA.gov, Last Updated May 4, 2021). https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ethiopia/#:~:text=Ethnic%20groups,%25%2C%20Afar%20(Affar)%20 (May 8, 2021)

While Menelik II successfully defended his empire against an Italian invasion in 1895-96, Italy assumed control over the region of Eritrea. After Menelik’s death in 1913 and a period of political transition, Emperor Haile Selassie I ascended to the throne in 1930. Haile Selassie is believed to be of both Oromo and Amhara descent, but his claim to the throne rested on his Amhara grandmother’s royal lineage.4Seifudein Adem, Marcel Kalenga, Cynthia Cai, Binoy Kampmark, Christopher Clugston, and Brian Gruber. The Oromo of Eastern Africa: Ali Mazrui’s Perspective, (Intpolicydigest.Org, February 26, 2018). https://intpolicydigest.org/the-oromo-of-eastern-africa-ali-mazrui-s-perspective/ (Feb. 22, 2021)

After ascending to power, Haile Selassie held the throne for only five years before another Italian invasion of Ethiopia led by Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini forced him to flee the country. Haile Selassie was restored to power in 1941 and then, in 1962, expanded his territory through the annexation of Eritrea, which sparked an Eritrean independence struggle that lasted for 30 years.5Thomas Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, “The Liberation Struggle in Eritrea,” in Ethiopia: A Country Study, (Country Studies, Library of Congress, 1991). http://countrystudies.us/ethiopia/ (Feb. 24, 2021) Haile Selassie’s reign was also marked by a series of insurrections in response to high taxes and the central government’s degradation of regional autonomy, including the 1943 Woyane Rebellion in Tigray and the Gojjam insurrection in 1968.6Thomas Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, “Discontent in Tigray,” in Ethiopia: A Country Study, (Country Studies, Library of Congress, 1991). http://countrystudies.us/ethiopia/ (Feb. 24, 2021)

The prospect of famine loomed large in these conflicts. In part, this is a result of Ethiopia’s dependency on rain-fed agriculture to produce the resources required for survival. Food insecurity in the country is heavily impacted by erratic rainfall and droughts. 7The Facts: How We’re Fighting Hunger in Ethiopia, (Mercycorps.Org, June 27, 2019). https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/fighting-hunger-ethiopia (Feb. 20, 2021) Though climate has played its part, the country’s famines were also fundamentally tied to ethnic conflict, war, and revolution.8“Introduction,” in Evil Days, 30 Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia, (Africa Watch, Human Rights Watch, 1991). https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/Ethiopia919.pdf (Feb. 21, 2021), 4-5.

Under the rule of Haile Selassie, famine took place in areas where populations openly resisted the regime. In Tigray, revolts against the emperor were met with aerial bombing and land confiscation, which resulted in severe famine in 1958. Wollo also experienced famines in 1965 and 1972, caused both by drought and the central government’s responses to uprisings in the region, which included looting, the confiscation of cattle, and the impediment of the salt trade.9“Rebellion and Famine in the North under Haile Selassie,” in Evil Days, 30 Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia, (Africa Watch, Human Rights Watch, 1991). https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/Ethiopia919.pdf (Feb. 21, 2021), 55. These famines resulted in the deaths of thousands and were largely ignored by the central government.

The 1972 famine in Wollo was widely reported on by the international community and was a substantial factor in the overthrow of Haile Selassie in 1974 by the Derg, a pro-Soviet military regime.10Ibid., 58. 11“Scorched Earth in Eritrea, 1961-77,” Evil Days, 30 Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia, (Africa Watch, Human Rights Watch, 1991). https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/Ethiopia919.pdf (Feb. 21, 2021), 47. However, despite the change in government, famine and conflict remained constant threats within the country. In October 1984, the international community was shocked by pictures of a “biblical famine” in the border regions between Tigray and Wollo.12Peter Gill, “The Famine Trail,” in Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid, (South African History Online, 2010). https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/file%20uploads%20/peter_gill_famine_and_foreigners_ethiopia_sincebook4you.pdf (Feb. 25, 2021) Like the famines before it, this disaster could not only be explained by insufficient rainfall, as the Ethiopian army’s counter-insurgency strategy against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) was also a driving factor.

The TPLF was founded in 1975 in the mountainous northern region of Tigray.13Aregawi Berhe, The Origins of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, (African Affairs, Vol. 103, No. 413, Oxford University Press, 2004). https://www.jstor.org/stable/3518491?seq=1 (March 11, 2021) Through the late 1970s, the TPLF steadily gained popularity with the Tigrayan people by emphasizing the threat posed to local traditions and regional autonomy by the central government. The TPLF compounded their rise to power by allying with nationalist rebels from the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF).14Thomas Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry,” The Tigrayan Movement,” in Ethiopia: A Country Study, (Country Studies, Library of Congress, 1991). http://countrystudies.us/ethiopia/ (Feb. 20, 2021) Given the popularity of the TPLF amongst the Tigrayan ethnic group populating the region, the Derg responded to this insurgency with a counter-population strategy focused on military offensives aimed at the surplus-producing districts, aerial bombardment of markets, and travel controls on migrants and traders in the region. These three core elements of the Derg’s larger counter-insurgency strategy prevented the traditional redistribution of surplus food in the region, leading to the famine that followed.15“Counter-Insurgency and Famine in Tigray and its Borderlands, 1980-84,” in Evil Days, 30 Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia, (Africa Watch, Human Rights Watch, 1991). https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/Ethiopia919.pdf (Feb. 25, 2021)

A major aspect of the Derg’s relief response to the famine, the relocation of much of the Tigrayan peoples to other areas of the country, was also a key part of its counter-insurgency plan. By removing the population that supported the TPLF, the Derg was implementing a brutal counterinsurgency tactic best described as ‘draining the sea to catch the fish.’16Peter Gill, “Hunger as a Weapon,” in Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid, (South African History Online, 2010). https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/file%20uploads%20/peter_gill_famine_and_foreigners_ethiopia_sincebook4you.pdf (Feb. 20, 2021) While this strategy—and the death and suffering that resulted—was condemned internationally, it is likely that the program’s huge costs and ineffectiveness as a tactic played as much or more of a role in its eventual shutdown than international pressure. The Derg was supported by the Soviet Union in the context of the Cold War, and the weaponization of famine did little to change that support—although there is evidence that the Soviet Union began cutting its military support in favor of political solutions in 1987.17Thomas Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, “The Derg, the Soviet Union, and the Communist World,” in Ethiopia: A Country Study, (Country Studies, Library of Congress, 1991). http://countrystudies.us/ethiopia/ (Feb. 20, 2021)

While the 1982-84 famine severely hampered the TPLF in the short-term, its long-term impact was the unification and mobilization of the Tigrayan people under the TPLF’s and EPLF’s authority. The central government’s strategy alienated the Tigrayan population, and, in response, they rallied around the banners of these revolutionary groups. The number of troops the TPLF could mobilize in the late 1980s rose by threefold, and the organization found that it could rely on support from the Tigrayan population when conducting guerilla operations.18“Insurgency Strategy of the TPLF,” in Evil Days, 30 Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia, (Africa Watch, Human Rights Watch, 1991). https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/Ethiopia919.pdf (Feb. 23, 2021)

The late 1980s saw the turning point of the war with the creation of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF)—a coalition of revolutionary forces from all over the country, including the TPLF. In 1991, the EPRDF occupied Addis Ababa, bringing an end to the central government.19Anthony Low, Eastern Africa, Fall of Military Governments, (Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, inc., last updated July 12, 2019). https://www.britannica.com/place/eastern-Africa/Fall-of-military-governments#ref419041 (Feb. 26, 2021) While EPRDF began organizing an ethnically based government, codified under a 1994 constitution, the EPLF declared independence for Eritrea, which was recognized in 1993.20G. W. B Huntingford, The Constitutional History of Ethiopia, (Journal of African History 3 (2), Cambridge University Press, 2009). https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/abs/constitutional-history-of-ethiopia/723AFA600ECFEAA1382AD8E0CDF4FC68 (Feb. 20, 2021) In 1998, Eritrea and Ethiopia became embroiled in a border war, with a final peace only being reached in 2018.21Susan Stigant, Michael V. Phelan, A Year after the Ethiopia-Eritrea Peace Deal, What Is the Impact?, (United States Institute of Peace, 2019).

Conflict in Tigray

Under the 1994 constitution, the Ethiopian government became a republic with a powerful prime minister, a primarily symbolic president, and the legislature composed of two chambers; the House of Peoples’ Representatives and the House of the Federation.22 Ethiopia’s Constitution of 1994, (Constitute Project). https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Ethiopia_1994.pdf?lang=en (March 2, 2021) As opposed to Ethiopia’s previous forms of government under Haile Selassie and the Derg, the constitution also created nine ethnically-based regional states, which operate with a large degree of autonomy and possess the right to self-determination, up to and including secession.23“Government” in Ethiopia, (The World Factbook, CIA.gov, Last Updated May 4, 2021). https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ethiopia/#government (May 8, 2021)

While Tigrayans are a small minority of Ethiopia’s population, the TPLF managed to maintain its position as a dominant party through the EPRDF for decades.24Jason Burke, Rise and Fall of Ethiopia’s TPLF – from Rebels to Rulers and Back, (The Guardian, 2020). http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/25/rise-and-fall-of-ethiopias-tplf-tigray-peoples-liberation-front (March 1, 2021) This dominance was illustrated by Tigrayan influence over national politics and the military through the holding of key leadership positions. This power sharing arrangement was recalibrated in 2018 with the election of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed—an ethnic Oromo—who came to power on a wave of growing frustration with the perceived rule of the Tigrayan ethnic minority.25Alex De Waal, Tigray Crisis Viewpoint: Why Ethiopia Is Spiraling out of Control, (BBC News, November 15, 2020). https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54932333 (March 1, 2021) Upon assuming office, Ahmed immediately reordered the status quo both by weakening Tigrayan dominance over Ethiopia’s armed forces and by restoring relations with Eritrea through agreeing to implement the peace accord of 2000. Ahmed’s peace deal with Eritrea won him the Nobel Peace Prize and international acclaim. However, it also had the more sinister consequence of isolating the TPLF between Eritrea, Amhara ethno-nationalists, and the federal government—all of whom were nursing grievances towards the TPLF.26Yosief Ghebrehiwet, The ‘Peace’ That Delivered Total War against Tigray, (Ethiopia-Insight.Com, January 23, 2021). https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2021/01/23/the-peace-that-delivered-total-war-against-tigray/ (February 28, 2021)

Critics of Ahmed believe that much of this reordering was done to further his ultimate goal of abolishing Ethiopia’s system of multinational federalism in favor of a more unitary and centralized system of government. These critics cite Ahmed’s romanticization of Ethiopia’s imperial past and his desire to ‘make Ethiopia great again.’27Awol K. Allo, How Abiy Ahmed’s Ethiopia-first nationalism led to civil war, (Aljazeera, November 25, 2020). www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/11/25/how-abiy-ahmeds-ethiopia-first-nationalism-led-to-civil-war (March 8, 2021) This ideology is fundamentally at odds with the ideology of the TPLF and necessitates their decreased political and military influence.

In the face of this recalibration of power, the TPLF refused to join a new political party set up by Ahmed to replace the old ruling coalition. Then, in September 2020, they proceeded with local elections in Tigray despite a federal decision to postpone elections due to the coronavirus pandemic. During the night of November 3, 2020, TPLF forces attacked federal forces stationed in the region. While TPLF has made the claim that this was merely a preemptive strike against the federal government, the attack triggered the current conflict.28Jordan Anderson, Africa Conflict Series: Ethiopia, (IHS Markit, January 14, 2021). https://ihsmarkit.com/research-analysis/africa-conflict-series-ethiopia.html (May 8, 2021)

After a wide federal mobilization of troops and weeks of fighting, the federal government declared victory after taking Tigray’s capital city, Mekelle, on 28 November 2020.29Cara Anna, Ethiopia declares victory as military takes Tigray capital, (AP NEWS. Associated Press, November 28, 2020). https://apnews.com/article/ethiopia-abiy-ahmed-kenya-0fb8647516d9be83d45fee2f1e4d13ae (April 27, 2021) As of February 2021, however, reports from independent actors indicate an increase of fighting and human rights abuses in the region. Eritrean troops and Amhara militias have also entered the conflict in support of the federal government, with additional reports indicating widespread human rights abuses against the Tigrayan people at their hands.30Ethiopia: Eritrean Forces Massacre Tigray Civilians, (Human Rights Watch, March 5, 2021). https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/05/ethiopia-eritrean-forces-massacre-tigray-civilians (March 7, 2021) While the federal government has denied these claims—only in March admitting to the presence of Eritrean troops in the region—and broader claims of human right abuses, independent actors’ reports indicate the continued deterioration of humanitarian conditions. More than 4.5 million people in Tigray reportedly require emergency food aid and hundreds of thousands could starve.31Paul Richardson, Ethiopia Criticizes Amnesty Report on Massacre in Tigray, (Bloomberg News, February 27, 2021). https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-27/ethiopia-criticizes-amnesty-report-on-massacre-in-tigray-town (March 4, 2021); Finding a Path to Peace in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region, (Crisis Group, February 11, 2021). https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/167-finding-path-peace-ethiopias-tigray-region (Feb. 27, 2021) According to the Famine Early Warning System’s Network, which has tracked and produced analysis on food insecurity since the 1980s, emergency and crisis food security outcomes are expected across central, northwestern, and eastern areas of Tigray.32Ethiopia, (Famine Early Warning System, 2021). https://fews.net/east-africa/ethiopia (March 2, 2021)

This disaster is only getting worse, in large part because of the fundamental lack of access for international humanitarian actors due to the federal government’s restrictions and changing regulations.33Ben Parker, Only a Trickle of Help Is Getting into Tigray. Here’s Why, (The New Humanitarian, February 11, 2021). https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2021/2/11/Humanitarian-access-stalled-in-Ethiopia-Tigray (March 2, 2021) As a result of these federal policies and protocols, the Ethiopian Red Cross in February stated that almost 5 million people in the region were classified as unreachable in the context of the delivery of humanitarian aid.34Cara Anna, Emaciated’ survivors hint at worse in Ethiopia’s Tigray, (AP News. Associated Press, February 10, 2021). https://apnews.com/article/ethiopia-tigray-starvation-bc4b3d569137925c5c34d30ac1683664 (April 6, 2021)

Famine: The Tactical Incentive

If fears are realized and the federal government is actively preventing food security aid from reaching Tigray, the moral and strategic consequences are profound. However, within the context of the federal government’s stated goal of complete victory, there is a tactical, if twisted, incentive for the weaponization of food insecurity.

As observed by many military leaders throughout history, armies ‘march on their stomachs.’ Multiple studies in sub-Saharan Africa show that areas with a higher per capita availability of freshwater and edible vegetation are more likely to experience protracted conflicts.35“Box 2. Food as a weapon of war: Agri-terrorism” in Winning The Peace: Hunger and Instability, (World Food Program USA, 2017). https://www.wfpusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2017-Winning-the-Peace-Hunger-and-Instability.pdf (Feb. 26, 2021) This understanding of food as a prerequisite for extended conflict is also prevalent in the humanitarian sphere. Some experts argue that humanitarian aid can unintentionally extend civil wars by providing combatants with the resources and the corresponding political will they need to continue resistance.36Neil Narang, Assisting Uncertainty: How Humanitarian Aid Can Inadvertently Prolong Civil War, (International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 1-12, page(s): 12, Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation, 2014). https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/assisting-uncertainty-how-humanitarian-aid-can-inadvertently-prolong-civil-war (March 2, 2021) While the consequential claim that humanitarian aid can ultimately result in more suffering by extending conflict is hotly contested, the foundational understanding behind the theory—a starving population loses the means and the will for conflict—is not a novel concept. There is a plethora of examples throughout history of sieges breaking a population’s resolve through hunger, stretching from the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD to President Bashar al-Assad’s widespread use of siege in the last decade against Syrian rebels.37Kathleen Lohnes, Siege of Jerusalem, (Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, inc., August 29, 2018). https://www.britannica.com/event/Siege-of-Jerusalem-70 (May 8, 2021); Karin Laub, Siege Warfare in Syria Revives Debate over Ancient Tactic, (AP NEWS. Associated Press, February 17, 2016). https://apnews.com/article/859b168c4d6b493bb803bb78dd8fe091 (May 8, 2021)

Understanding this, the federal government may perceive a tactical incentive to inducing hunger in Tigray as a means of winning the war. This is doubly true if Ahmed’s fundamental goal is the abolishment of Ethiopia’s multinational federalism and the creation of a more powerful centralized federal state.38Soreti Kadir, Ayantu Ayana, Abiy Ahmed’s Plot against Multinational Federalism in Ethiopia, (War Scapes, July 20, 2020). http://www.warscapes.com/opinion/abiy-ahmed-s-plot-against-multinational-federalism-ethiopia (March 2, 2021) While relatively small in numbers, the Tigrayan ethnic group has historically been a thorn in the side of any regime attempting centralization of power. Many Ethiopians also claim, with some justification, that the TPLF used their political power in the last two decades to commit human rights violations against other ethnic groups in the country.39“Ethiopia,” in World Report 2012, (Human Rights Watch, 2012). https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2012/country-chapters/ethiopia (Feb. 25, 2021) This combination of political goals and popular sentiment is the likely impetus for the expressed goal of total victory over the TPLF, defined as the fundamental dismantling of the leadership and larger organization.

Given the TPLF’s grassroots structure, their dismantling will only come about either through the TPLF losing the popular support of the Tigrayan people or the fundamental undermining of Tigrayan ethnic and cultural identity. As most voting-age Tigrayans voted in the most recent September election in favor of the TPLF, in direct opposition to directives from the federal government, the federal government does have indications that eroding the TPLF’s popular support is an unlikely possibility in the current context.40Finding a Path to Peace in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region, (Crisis Group, February 11, 2021). https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/167-finding-path-peace-ethiopias-tigray-region (Feb. 27, 2021)

The aim of total victory is also undoubtably being pursued by Ahmed’s allies, including the Amhara militias that have felt politically disenfranchised over recent decades after having been previously associated with the ruling family of the Ethiopian Empire for centuries. Furthermore, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki is seeking total victory as a means of maintaining his own grip on power. The porous Eritrea-Tigray border has allowed many young Eritreans to flee the internal repression within the country to the welcoming arms of Tigray, which has resulted in a youth drain for Eritrea and a growing community of dissidents opposed to Afwerki right across his border.41

The War in Tigray: Abiy, Isaias, and the Amhara Elite, (The Africa Report, Ethiopia Insight, January 29, 2021). https://www.theafricareport.com/62232/the-war-in-tigray-abiy-isaias-and-the-amhara-elite/ (March 2, 2021)

In the context of these goals, famine is a useful, if not welcome, tool as it either kills or displaces the Tigrayan population. Unlike past conflicts, the Tigrayans are hemmed in on multiple sides. The region is bordered by the rest of Ethiopia to the south and east, while Eritrea sits to its north. Those seeking to escape are thus left with the option of either fleeing to refugee camps in Sudan, through Tigray’s small western border with that country, or dispersal throughout Ethiopia. As they flee, Amhara militias stand ready to fill the vacuum and ‘reclaim’ land they believe was stolen from them during the division of Ethiopia into ethno-political states. If such a population dispersal is effective, the TPLF’s greatest strength, the wide support of the local population, will be negated.

The Strategic Repercussions of Famine

With total victory as the ultimate aim, famine in Tigray serves tactical and even short-term strategic goals. In the long-term, however, its strategic consequences far outweigh its incentives.

While resources are necessary to wage conflict, a lack of resources can serve as an underlying cause to a conflict, as food scarcity contributes to the escalation of social tensions and the collapse of social trust. Such conflict may enter periods of low-intensity or even dormancy during times of extreme deprivation, but if food insecurity is one of the root causes of the conflict, these periods of deprivation will only fuel the resentment that is driving the conflict forward.

In the context of Tigray, this phenomenon is vitally important. To create a real peace, the federal government must win popular acceptance by the Tigrayan population or be perceived as an occupying force, which will promote an ethnic insurgency in the Tigray region for generations to come. This is a story that has already played out numerous times throughout Tigray’s history, with past ethno-nationalist resistance being fueled only by insufficient aid or the weaponization of famine. The only other option is the dispersal of the population and its replacement by a more sympathetic group, such as the Amhara. However, this callous tactic is unlikely to succeed.

As was shown when the Derg attempted a similar strategy, it was unable to incentivize the intended portion of the Tigrayan population into resettlement, with a large portion of the impacted Tigrayans instead residing in areas already under the central government’s control. As this tactic and its consequences are still remembered by the Tigrayan people, it is likely to be even more unsuccessful if tried today. Additionally, while the federal government currently has the broad support of many Ethiopians in its conflict against the TPLF, such support will begin to erode in the face of mounting evidence of war crimes and human rights violations.

Ethiopia’s history shows that famine in one region can stir the sympathetic, unaffected populations of another to revolt. The fall of Haile Selassie was triggered by a famine in Wollo, but implemented by sympathetic and frustrated students, members of the middle class, and members of the military in the capital city of Addis Ababa.42Zahra Moloo, Ethiopia’s Unforgettable Famines: Here’s Why They Really Happen, (CBC News, CBS Documentary Channel, 2021). https://www.cbc.ca/documentarychannel/features/ethiopias-unforgettable-famines-heres-why-they-really-happen (March 2, 2021). Currently, a significant portion of Ethiopia’s population has little sympathy for the TPLF given their perceived use of power in the last two decades, but empathy is likely to mount in the face of human rights violations. Moreover, in the context of Ethiopia’s ethnically based government, the erosion of support for the federal government will not need to stem from empathy or morality alone, but rather a fear that their ethnic group is next.

Ethiopia has no single majority ethnicity, and Ahmed’s broader goal of the abolishment of multinational federalism is not necessarily shared by his allies. If the federal government successfully employs the weaponization of famine and other human rights abuses to further its goal of abolishing multinational federalism, it is a safe assumption that Tigray may not be the last region in Ethiopia to experience such tactics. In the current context of ethnonationalist sentiment and constitutionally defined ethnic political regions, the fundamental erosion of trust in the federal government resulting from a humanitarian disaster could even result in a Yugoslavia-style dissolution of country.

Geopolitical Implications

In addition to its intra-state impact, famine in Tigray weakens Ethiopia regionally. Ethiopia has traditionally been a regional power in the Horn of Africa, but with its attentions focused on Tigray, other actors are beginning to identify opportunities to strengthen their own position—a prime example being the recent border dispute between Ethiopia and Sudan.43Michelle Gavin, Ethiopia-Sudan Border Dispute Raises Stakes for Security in the Horn, (Council on Foreign Relations, February 10, 2021). https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/conflict-ethiopias-tigray-region-what-know (March 2, 2021) Potentially adding to this instability is Egypt’s and Ethiopia’s ongoing dispute regarding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).44John Mukum Mbaku, The controversy over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, (Brookings, August 5, 2020). https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/08/05/the-controversy-over-the-grand-ethiopian-renaissance-dam/ (March 29, 2021)

Ethiopia plans to use the GERD, which is located on the Blue Nile—a major tributary to the Nile—to transform it into one of Africa’s largest hydroelectric energy producers. To do so, the GERD must divert a large percentage of the Blue Nile into a reservoir, impacting the Nile downstream. Egypt, already water-stressed and dependent on the Nile for much of its freshwater, let alone its culture, views the GERD as a threat to its continued existence. Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt agreed to enter US-mediated talks in 2019, but Ethiopia began filling the GERD reservoir while negotiations were under way and has since left these negotiations.45

Patsy Widakuswara, No Deal from US-Brokered Nile Dam Talks, (Voice of America, February 29, 2020). https://www.voanews.com/africa/no-deal-us-brokered-nile-dam-talks (March 2, 2021) Given that Egypt views the GERD as an existential threat, it may seek to turn any instability in Ethiopia, including an ethnic insurgency, to its advantage.

The increasing potential for a humanitarian crisis in Tigray is also eroding Ethiopia’s support on the world stage. The European Union has already suspended budget support for Ethiopia worth 88 million euros ($104.75 million dollars) due to a lack of humanitarian access to the region.46EU Suspends Ethiopian Budget Support over Tigray Crisis, (Reuters, Reuters World News, January 15, 2021). https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-conflict-eu-idUSKBN29K1SS. (Feb. 28, 2021). Also worrisome for the federal government is the growing advocacy within the international community for the use of UN resolution 2417, which condemns the use of starvation and empowers the UN Security Council to impose sanctions for obstructing the delivery of aid.47Adopting Resolution 2417 (2018), Security Council Strongly Condemns Starving of Civilians, Unlawfully Denying Humanitarian Access as Warfare Tactics, (United Nations Meeting Coverage, Security Council, 8267th Meeting, May 24, 2018). https://www.un.org/press/en/2018/sc13354.doc.htm (March 5, 2021)

This erosion of international support could prove more consequential for Ethiopia than at any time in its past. In the last decade, Ethiopia’s largest aid contributors have been the United States, the United Kingdom, and the World Bank Group’s International Development Association (which counts on the United States and the United Kingdom as its largest contributors). 48Investments to End Poverty, (Development Initiatives, 2013). http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Investments_to_End_Poverty_full_report.pdf. (March 3, 2021); Contributor Countries, (World Bank Group, International Development Association, 2016). http://ida.worldbank.org/about/contributor-countries (March 6, 2021) While neither of these countries have yet cut aid to Ethiopia, both have separately called for de-escalation, with these calls increasingly hardening in language as the crisis continues.49

U.S. Is ‘Gravely Concerned’ By Reports of Abuses in Ethiopia, (Associated Press. POLITICO, February 28, 2021). https://www.politico.com/news/2021/02/28/abuses-ethiopia-blinken-state-471844 (March 6, 2021)

Ways Forward

The inhumane weaponization of famine in Tigray may result in short-term gains for the federal government and their allies in the furtherance of their broader goals, but the potential long term strategic consequences could undermine Ethiopian stability for decades to come. These consequences could include international repercussions, a weakened regional influence, and an ethnic insurgency that haunts the federal government’s steps and exacerbates any weakness.

Recognizing this, the federal government should instead shift their goals to convincing Tigrayans to work with the interim government on rebuilding Tigray. To do this, it will have to ensure the full and verifiable removal of Eritrean forces from the region, which reportedly began in early April.50Ethiopia says Eritrean troops have started withdrawing from Tigray, (Reuters, Reuters Middle East & Africa, April 4, 2021). https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-conflict/ethiopia-says-eritrean-troops-have-started-withdrawing-from-tigray-idUSKBN2BR05A?il=0 (April 6, 2021) Additionally, Ahmed will have to exert his political influence over his Amhara supporters, who comprise his central support base, and incentivize the roll back of Amhara militias’ advances in the region. The federal government must also allow full humanitarian access to the region and even consider granting amnesty to some of the former leaders of the TPLF. Once a humanitarian disaster is averted and the process of rebuilding has begun, the federal government can turn to creating comprehensive dialogue throughout the country on the issue of a multinational federalism.

This dual track approach will be a long process and will undoubtably be plagued by setbacks. However, it is also the only chance Ethiopia has at maintaining some semblance of stability, while still actively entertaining the prospect of political reform. Simply put, an uncertain chance of a transition into a new political structure that remains peaceful and does not inflame ethnic tensions is highly preferrable to a humanitarian disaster that is likely to only result in the destabilization—if not dissolution—of the country.

Based on your interests, you may also wish to read:

- Confronting the Overlap of Sextortion and Natural Resources in Kenya

- Overlapping Insecurities: Maritime and Agrarian Resource Management as Counterterrorism

- The Lesotho Highlands Water Project’s Perpetuation of Inequity and Food Insecurity Among Women

- Imperial Reckoning: an exceptional investigation into the violence and brutality which characterized the end of empire in Kenya