United States Refugee Resettlement during the COVID-19 Pandemic as it Relates to African Migration

Solomon Tejada Brown, Senior Research Analyst, Leadership and Governance Policy Lab

stbrown@africacfsp.org

Ray Schneider, Research Analyst, Leadership and Governance Policy Lab

rschneider@africacfsp.org

African refugee migration to the United States traditionally represents the majority of the total amount of refugees that are both anticipated and ultimately resettled in the U.S. per annum. Therefore, when U.S. policies underwent sudden changes in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, African migration was affected the most. U.S. policies towards refugee migration to the U.S. had already endured a host of steady changes leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. This report looks to analyze these policy changes and determine the effects they had on the migrants.

Introduction

American policy has always been fluid in regard to resettling refugees from conflict zones. Every administration sets an upper ceiling for how many refugees will be allowed to resettle in the United States, and each administration has different goals when it comes to setting the admission ceiling. This results in resettlement targets that shift from year to year, but targets have hovered between 80,000 and 100,000 for the past two decades.1Ryan Baugh, Fiscal Year 2020 Refugees and Asylees Annual Flow Report (Department of Homeland Security, 2022). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a disastrous impact on the resettlement process, with drastically reduced resettlement targets and the shutdowns of various government organizations negatively impacting the ability of the United States to aid those who need it most.

Prior to the pandemic, the United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) used to be a fairly straightforward, albeit restrictive, system to navigate. Anyone applying as a refugee to be resettled in the United States had to go through a lengthy process involving interviews to determine eligibility and numerous medical and security checks. However, the shutdown of many government organizations in response to COVID-19 has effectively thrown the future of many applicants in limbo.2Jonathan House Residents, We Want to be treated like Human Beings (International Association for Refugees, 2021). Refugees who may have been cleared for resettlement in the United States are waiting for travel documents that will never arrive. Even if they have documents, they still may not be able to enter the United States if travel is restricted from their country of origin.

Changes to U.S. immigration policy have severely reduced the flow of African refugees to the United States. In recent years, African refugees have made up between 30% to 50% of all refugees resettled in the United States annually.3Ryan Baugh, Annual Flow Report, Refugees and Asylees: 2019 (Department of Homeland Security, 2020). The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Eritrea, and Sudan were three of the top ten countries of nationality for refugees resettled by volume in the United States.4Ryan Baugh, Fiscal Year 2020 Refugees and Asylees Annual Flow Report (Department of Homeland Security, 2022). Long running security crises in these regions, as well as new outbreaks of violence in Ethiopia, have meant that many Africans are desperately seeking safety in other countries, even though COVID-19 restrictions such as lockdowns and border closures have made travel very difficult. These restrictions meant that resettlement of African refugees to the United States was significantly lower in 2020 than any recorded year. This is not because less people applied for resettlement in the United States, but because it has become much harder to do so.

Timeline of Resettlement Metrics

Under the Refugee Act of 1980, before the beginning of every Fiscal Year (FY) and in consultation with Congress, the President of the United States establishes a Refugee Admissions Ceiling. Political pressures on United States immigration policy saw that FY2020 had the lowest historically recorded Refugee Admissions Ceiling and an even lower refugee arrival rate. While this was largely due to the changes in policy prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, this historic low follows a four-year downward trend commencing with the change of Presidential Administrations in 2017. It is important to note that forced human migration from African countries to the U.S. generally takes the form of approved refugee resettlement, rather than individuals seeking asylum. There are migrants from African countries that seek asylum in the United States; however, the disparity between these individuals and the African migrants who utilize the U.S. Refugee Resettlement system is significant to the point of mentioning.

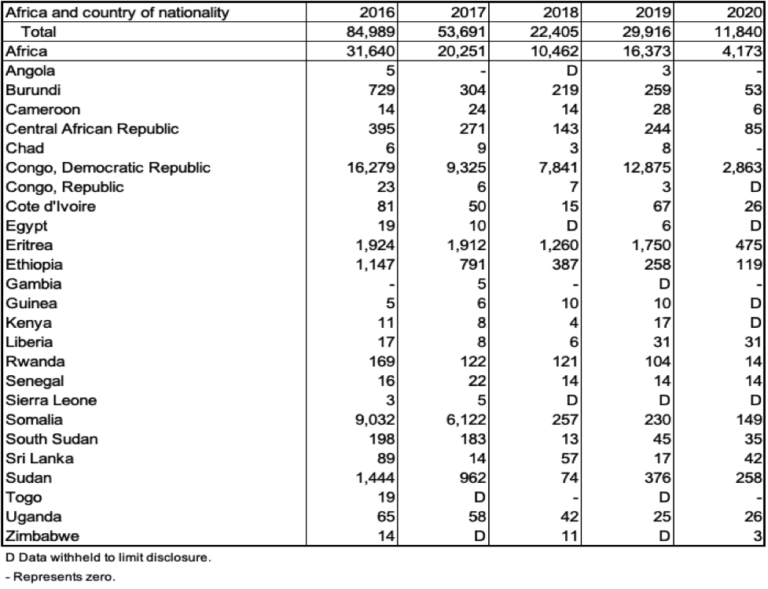

Table 1. Refugee Admissions by African Nation: Fiscal Years 2016 to 2020

As shown in Table 1, African refugee migration is primarily from the DRC and secondarily from Somalia. Resettlement across the board decreases across five federal fiscal years, beginning with FY2016 which was the final year of the Obama Administration.

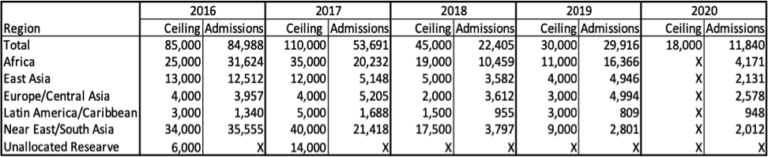

Table 2. Proposed and Actual Refugee Admissions by Regions: Fiscal Years 2016 to 2020

Historically, African refugee migration takes the lion’s share of the approved annual refugee admissions for each fiscal year. As seen in Table 2, African migration constitutes anywhere between 35% of the total year’s admissions (FY2020) to 55% (FY2019). This vastly overshadows the admission of migrants from other regions around the world. Even with the extraordinarily low admissions in FY2020, African refugees still made up the bulk of the fiscal year’s approved resettlements.

Table 2 further shows the numeric change in general refugee admissions across the fiscal year timeline. Though FY2017 was the beginning of the Trump Administration, it was the previous administration that set the proposed Refugee Admission Ceiling at 110,000 individuals, a near two-decade record high. Regardless of the high FY2017 Refugee Admission Ceiling set by the previous administration, FY2017 saw a 36.83% decrease in overall admissions from the previous year and a near equal decrease to resettlement of African migrants. By FY2020, the Refugee Admission Ceiling had dropped 83.64% from FY2017 and the admissions dropped 77.95%. Migration specifically from Africa decreased 86.81% from FY2016 and 79.38% from FY2017.

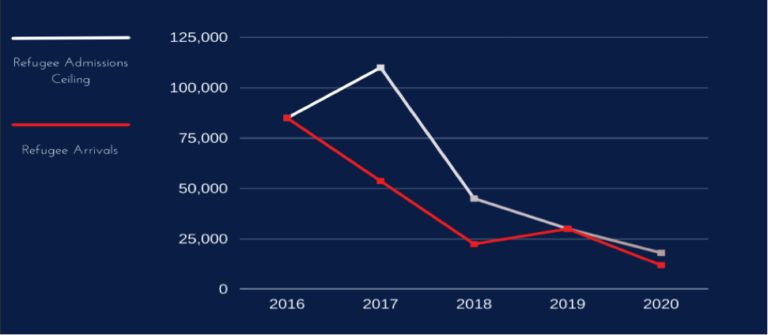

Figure 1. Proposed and Actual Refugee Admissions: Fiscal Years 2016 to 2020

As shown in Figure 1, the resettlement downward trend is shown numerically beginning in FY2017. This trend continues to FY2020 which, as mentioned before, shows the lowest recorded refugee admissions ceiling and actual refugee resettlement.

Outside of the political pressures, the COVID-19 pandemic played a significant role in U.S. policy changes regarding the FY2020 refugee admissions rate.

Timeline of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Related Shifts in U.S. Policy:

- January 9, 2020: WHO announces mysterious coronavirus-related pneumonia in Wuhan, China10“Who Statement Regarding Cluster of Pneumonia Cases in Wuhan, China,” World Health Organization (World Health Organization), accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/09-01-2020-who-statement-regarding-cluster-of-pneumonia-cases-in-wuhan-china.

- January 21, 2020: CDC confirms first U.S. Coronavirus Case11“First Travel-Related Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 21, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html.

- January 31, 2020: WHO issues Global Health Emergency12“Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-Ncov),” World Health Organization (World Health Organization), accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

- January 31, 2020: Travel restrictions begin to be set in place for certain global regions13Michael Corkery and Annie Karni, “Trump Administration Restricts Entry into U.S. from China,” The New York Times (The New York Times, January 31, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/31/business/china-travel-coronavirus.html.

- January 31, 2020: U.S. declares a Public Health Emergency14“Determination That a Public Health Emergency Exists,” ASPR, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions/phe/Pages/2019-nCoV.aspx.

- March 11, 2020: WHO declares COVID-19 a Pandemic15“Who Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020,” World Health Organization (World Health Organization), accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020.

- March 13, 2020: U.S. President Trump declares COVID-19 a National Emergency16“Covid-19 Roundup: Coronavirus Now a National Emergency, with Plans to Increase Testing,” AJMC (AJMC, July 30, 2020), https://www.ajmc.com/view/covid19-roundup2.

- March 16, 2020: Travel ban on non-U.S. citizens traveling from Europe goes into effect17“Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain Additional Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus: Proclamation 9993 of March 11, 2020,” Federal Register, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/16/2020-05578/suspension-of-entry-as-immigrants-and-nonimmigrants-of-certain-additional-persons-who-pose-a-risk-of.

- March 17, 2020: U.S. Immigration court closures18Doj Eoir, “Effective March 18 All Non-Detained Hearings Postponed; These Immigration Courts Closed: ATL Peachtree; Charlotte; Hou Gessner; Louisville; Memphis; NYC, Broadway & Fed Plaza; Newark; Sacramento; Los – Olive,” Twitter (Twitter, March 18, 2020), https://twitter.com/DOJ_EOIR/status/1240124718298038273.

- March 18, 2020: Worldwide visas are suspended19Rae Alexander, “U.S. Visa Services Suspended Worldwide: International Student & Scholar Services (ISSS),” International Student Scholar Services ISSS, March 18, 2020, https://isss.uconn.edu/2020/03/18/u-s-visa-services-suspended-worldwide/.

- March 18, 2020: Refugee entry into the U.S. is suspended20Priscilla Alvarez, “Refugee Admissions to the US Temporarily Suspended,” CNN (Cable News Network, March 18, 2020), https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/18/politics/us-refugee-admissions-coronavirus/index.html.

- March 20, 2020: U.S. halt on operations assisting Asylum seekers21“US Policy Developments: March 2020 – July 2020,” The Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS), January 12, 2022, https://cmsny.org/us-policy-developments-2020-covid/.

- April 22, 2020: U.S. legal immigration is suspended22“Suspension of Entry of Immigrants Who Present a Risk to the United States Labor Market During the Economic Recovery Following the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak: Proclamation 10014 of April 22, 2020,” Federal Register, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/04/27/2020-09068/suspension-of-entry-of-immigrants-who-present-a-risk-to-the-united-states-labor-market-during-the.

- July 29, 2020: U.S. refugee resettlement is resumed23lvarez, Priscilla. “Refugee Admissions to the US Resume after Being on Pause Due to Coronovirus | CNN Politics.” CNN. Cable News Network, August 12, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/12/politics/refugee-admissions-coronavirus/index.html#:~:text=(CNN)%20Refugee%20admissions%20to%20the,according%20to%20the%20State%20Department.&text=The%20pause%20has%20already%20disrupted,US%20after%20an%20arduous%20process.

These COVID-19 related shifts in U.S. policy regarding international travel, refugee admissions, and foreign immigration had dramatic effects on the U.S. refugee resettlement infrastructure. Overnight, resettlement efforts for both international refugees and asylum seekers at American borders were halted. Between the sudden cessation of vital government operations related to U.S. refugee resettlement and the newly implemented travel restrictions, the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on the U.S.’ resettlement infrastructure. By direct relation, this significantly affected the rate of African resettlement to the U.S.

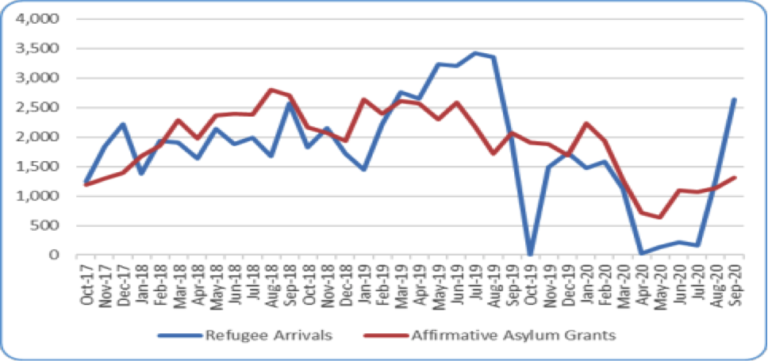

Figure 2 illustrates that the U.S. refugee resettlement rate dropped to zero at the onset of the travel and immigration restrictions enacted in March of 2020. Resettlement increased significantly in July of 2020 when COVID-19 related travel and immigrations restrictions were eased or lifted.

Anecdotal Evidence/ Personal Stories

It is important to remember that these statistics are not just numbers. Only 4,171 African refugees were allowed to be relocated in the United States in 2020; this is only a quarter of the amount resettled during the previous year.25Ryan Baugh, Fiscal Year 2020 Refugees and Asylees Annual Flow Report (Department of Homeland Security, 2022). Assuming the resettlement ceiling for 2020 was originally similar to that of 2019, what effect has the COVID-19 pandemic had on the thousands of refugees seeking asylum in the United States that were not able to be resettled?

The closure of borders and government organizations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has had an extremely negative effect on refugees in Africa. The most obvious of these is the fact that closed borders severely limit transnational travel. Deteriorating security situations in the Sahel and Ethiopia have seen almost 750,000 newly displaced people who fled to sprawling refugee camps.26UNHCR Statistics and Demographics Section. “UNHCR Global Trends – Forced Displacement in 2020.” UNHCR Flagship Reports. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, June 18, 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/flagship-reports/globaltrends/. Even though these camps are administered by the United Nations, the people who rely on them for protection are still not safe — as evidenced by the massacres in the Hitsats and Shimelba camps.27United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. “UNHCR Reaches Destroyed Camps in Northern Tigray.” UNHCR. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, March 26, 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/briefing/2021/3/605da0564/unhcr-reaches-destroyed-camps-northern-tigray.html. In cases like these, it is still not possible to resettle refugees in neighboring safe countries. Amnesty International reports that in May of 2020, up to 10,000 people fleeing the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo were living in an impromptu camp on the Ugandan border because they were unable to leave their country due to border closures in March of 2020.28Amnesty International. “East Africa: People Seeking Safety Are Trapped at Borders Due to COVID-19 Measures.” Amnesty International, June 22, 2020. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/06/east-africa-people-seeking-safety-are-trapped-at-borders-due-to-covid-19-measures/. If it was this difficult to get out of a conflict zone to a neighboring safe country, then resettlement in the United States would be nigh-impossible.

The added difficulty in resettling refugees in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic is certainly reflected in the numbers. In more normal years, the United States considers resettlement applicants based on three categories. P-1 is the category that covers individuals who have been referred to the USRAP by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), certain NGOs, or a U.S. Embassy. P-2 covers groups of humanitarian concern, and P-3 is only used in family reunification cases. However, in 2020, the USRAP only accepted refugees for resettlement if they had been referred by the UNHCR.29Ryan Baugh, Fiscal Year 2020 Refugees and Asylees Annual Flow Report (Department of Homeland Security, 2022). In short, only a fraction of refugees classified as P-1 (not all) were eligible to be resettled in the United States in 2020.

The limitations for resettlement, coupled with office closures throughout 2020, have been disastrous for those who rely on these processes to get themselves and their families to safety. Researchers from the Africa Center for Strategy and Policy spoke to individuals from the International Association for Refugees (IAFR) to understand the hidden impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on refugee populations. The most visible issue is that these new restrictions have caused serious delays in the resettlement process. One individual staying at the IAFR’s Jonathan House has been waiting almost 7 years for their application to be processed.30Jonathan House Residents, We Want to be treated like Human Beings (International Association for Refugees, 2021). Some refugees who have made it to the United States are unable to reunite with their families, due to the temporary ban on accepting P-3 class refugees. The COVID-19 pandemic is not entirely to blame for these years of waiting; the Zelika refugee camp in Malawi has a population between 50,000 and 60,000 refugees, but the United Nations is only attempting to resettle 100 families from the camp each year.31Tornga, Jacob. Interview by Wesli Turner and Keifer Brown. January 21, 2022. However, it is unclear how many of those 100 refugees will actually be resettled in the United States; with new restrictions on travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is doubtful any from Zelika will have been resettled.

These long delays have effectively put the lives of refugees in limbo. An individual who worked in the Zelika camp in 2019-2020 reported that there was a general sense of hopelessness among many of the refugees living there. When individuals at the camp were asked about this, many pointed to the lack of information on how and why American refugee resettlement programs were being shut down due to COVID-19. This, coupled with the uncertainty of life in a refugee camp, effectively brings the lives of refugees grinding to a halt. Many refugees are unsure if they should pursue an education while waiting in the camp, or attempt to find employment, because they have no solid timetable for when they will be resettled in the United States or elsewhere.32Alvarez, Priscilla. “Refugee Admissions to the US Resume after Being on Pause Due to Coronovirus | CNN Politics.” CNN. Cable News Network, August 12, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/12/politics/refugee-admissions-coronavirus/index.html#:~:text=(CNN)%20Refugee%20admissions%20to%20the,according%20to%20the%20State%20Department.&text=The%20pause%20has%20already%20disrupted,US%20after%20an%20arduous%20process. COVID-19 has exacerbated this issue, for the U.S. government temporarily shut down agencies vital to the resettlement process, such as the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, as a response to the pandemic. USCIS field and asylum offices were closed from mid-March to early June, and this closure coincided with a historic 98% decrease in refugee admissions during that time.33Ryan Baugh, Fiscal Year 2020 Refugees and Asylees Annual Flow Report (Department of Homeland Security, 2022). Any part of the resettlement process that relies on these organizations to function was effectively put on hold with little to no warning or explanation to refugees, resulting in refugees and their families left waiting for documents that may never arrive.34Alvarez, Priscilla. “Refugee Admissions to the US Resume after Being on Pause Due to Coronovirus | CNN Politics.” CNN. Cable News Network, August 12, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/12/politics/refugee-admissions-coronavirus/index.html#:~:text=(CNN)%20Refugee%20admissions%20to%20the,according%20to%20the%20State%20Department.&text=The%20pause%20has%20already%20disrupted,US%20after%20an%20arduous%20process. The impact this abrupt shutdown had on mental health cannot be understated, and long term wellbeing for those waiting in camps cannot be attained without increased transparency on how and why changes in the United States affects them.

While the effects of COVID-19 on refugee resettlement in the United States have been extremely negative, 2021 and 2022 have introduced improvements to the resettlement system to hopefully ensure a brighter future for the process. Firstly, the Overseas Medical Examination does not require a COVID-19 vaccine.35“CDC Requirements for Immigrant Medical Examinations: COVID-19 Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/panel-physicians/covid-19-technical-instructions.html. This may seem like a negative, but considering the uneven rollout of vaccine stocks has left many developing countries unable to fully vaccinate their own populations, requiring all refugees to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 would slow down the resettlement process even further.36Priya Basu. “New Data Illuminates Acute Vaccine Supply & Delivery Gaps for Developing Countries.” World Bank Blogs, August 17, 2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/new-data-illuminates-acute-vaccine-supply-delivery-gaps-developing-countries. Another way to speed up the resettlement process would be to raise the application ceiling to a more normal level. Fortunately, newly elected President Biden agreed to raise the resettlement ceiling for FY2021 to 62,500 in May of that year.37Antony Blinken. “The President’s Emergency Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021 – United States Department of State.” U.S. Department of State. U.S. Department of State, May 3, 2021. https://www.state.gov/the-presidents-emergency-presidential-determination-on-refugee-admissions-for-fiscal-year-2021/. The admissions ceiling for FY2022 was increased even more to 125,000.38“Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2022 – United States Department of State.” U.S. Department of State. U.S. Department of State, September 20, 2021. https://www.state.gov/report-to-congress-on-proposed-refugee-admissions-for-fiscal-year-2022/#_Toc80119709. While the U.S. refugee resettlement infrastructure is still recovering from the challenges imposed by the previous administration and COVID-19 pandemic, steps in a more supportive direction are being taken. There are still serious changes needed to streamline the process to aid as many refugees as possible, but the future of refugee resettlement is not as grim as it appeared in 2020.

Conclusion and Recommendations

As described above, the refugee/asylee resettlement process in the United States is a delicate system of simultaneous moving parts. Navigating this complex bureaucracy has always been a daunting task for individuals to overcome before their safe resettlement in the United States. Resettlement hit a historic setback in 2020 due to internal political pressures, but mostly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. When government agencies temporarily halted their operations, the entire U.S. refugee resettlement structure became an unforeseen casualty. Travel restrictions, immigration court closures, along with other necessary government halted functions made U.S. resettlement a temporary impossibility. This cessation of the U.S. resettlement structure then created backlogs, buildups, and an administrative cataclysm. As a result, displaced individuals and their families were effectively thrown into an administrative abyss. Resettlement was able to resume but only under a litany of ever-changing policies and shifting rules dubbed “a new normal.”

As mentioned before, African refugees traditionally have a larger presence by volume within the American refugee resettlement infrastructure. When resettlement operations were temporarily halted and other related COVID-19 policy changes were implemented, African refugees were most affected. As of the date of this publication, there is little data on how many families were left in limbo in their countries of origin before being able to be resettled in the United States.

What we do know is the U.S. resettlement backlog created by COVID-19 related policy changes has caused severe ramifications that affected millions of refugees worldwide. The U.S. refugee resettlement structure is indeed recovering from the damage caused by the pandemic, but lessons can be learned from examining the issues that prevailed throughout 2020 to build a more robust resettlement process.

The recommendations are as follows:

- USRAP should focus on eliminating all backlogs created by COVID-19 related policy changes.

- U.S. policy should develop the capacity for the inclusion of private sponsorship to galvanize public support for resettlement.

- U.S. policy on Global Health Emergencies/pandemics should give special consideration to displaced persons who have reached a higher tier of vulnerability as well as expand protections for individuals whose vulnerability may be disproportionately affected by future global health policies.

Based on your interests, you may also wish to read:

- Imperial Reckoning: an exceptional investigation into the violence and brutality which characterized the end of empire in Kenya

- Prosperity & Poverty in Post-Independent Africa Debated

- An Emerging Landscape of Terror in Mozambique: Implications for the Southern African Development Community

- ECOWAS’ Response to Coups in West Africa, 2020-2021