Political Violence and Insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger: Understanding the Impact

Catherine Galley, Research Analyst, Leadership and Governance Policy Lab

cgalley@africacfsp.org

Terrorism, political violence, and insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has resulted in political instability. The increased possibility of violence and refugee movement across borders threatens neighboring countries. This report examines how terrorism, organised crime, migration, great power competition, and the need to ‘save face’ impacts European countries’ response to terrorism and political instability in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

Background

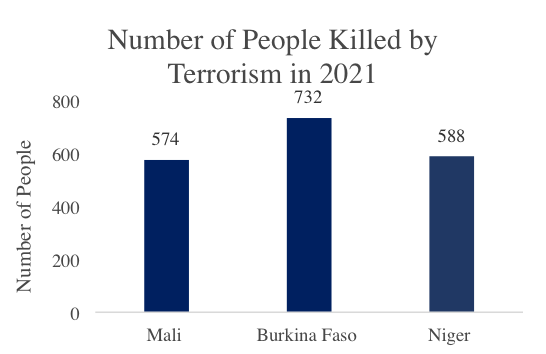

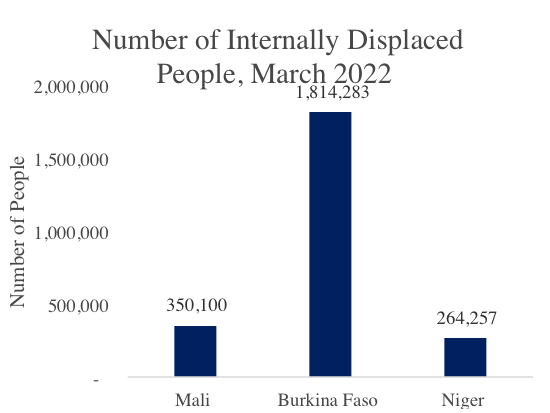

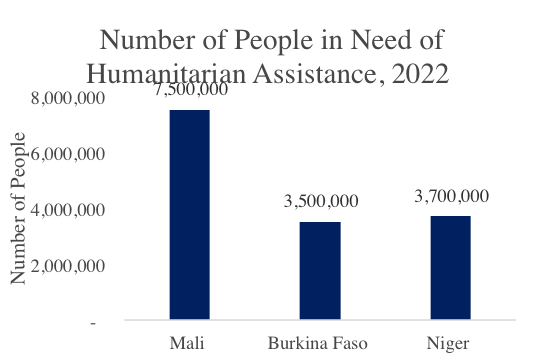

The Central Sahel is, as the Italian Institute for International Political Studies described, “one of the world’s quintessential fragile areas,” with 8.7 million people experiencing a state of crisis or famine between June and August 2021, 2 million people internally displaced, and more than 1,500 civilians killed in 2021 alone.1Strazzari, Francesco and Luca Raineri “Crisis to watch 2020: The Sahel” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 26 Dec. 2019. Accessed 31. Jan. 2022 https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/crisis-watch-2020-sahel-24705; Pichon, Eric and Mathilde Betant-Rasmussen “New EU strategic priorities for the Sahel” European Parliament Research Service. July 2021. Accessed 02 Feb. 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/696161/EPRS_BRI(2021)696161_EN.pdf; “Central Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger)” Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. 01 Dec. 2021. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. Most of the political instability is concentrated in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, though other Sahelian countries including Chad and Cameroon have also been affected by terrorist violence and political instability.2Strazzari, Francesco and Luca Raineri “Crisis to watch 2020: The Sahel” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 26 Dec. 2019. Accessed 31. Jan. 2022 https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/crisis-watch-2020-sahel-24705; Pichon, Eric and Mathilde Betant-Rasmussen “New EU strategic priorities for the Sahel” European Parliament Research Service. July 2021. Accessed 02 Feb. 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/696161/EPRS_BRI(2021)696161_EN.pdf; “Central Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger)” Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. 01 Dec. 2021. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. This report focuses on the impact of insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, and how this affects these countries, the wider region, and the West. The importance of understanding the situation in the Sahel is emphasised by Portugal’s Minister of Defence, who stated, “we need to address the growing arc of crises in our immediate neighbourhood because security crises and armed conflicts tend to be contagious, with multiple, often faraway impacts, that are difficult to predict,” adding that “the collapse of any of the Sahelian states would be a major risk for the security of North and West Africa, with significant knock-on effects for the security of Europe.”3Cravinho, João Gomes. “Foreword” in Taylor, Paul. “Crossing the wilderness: Europe and the Sahel” Friends of Europe. Spring 2021. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. https://www.friendsofeurope.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2021_PSD_PUB_Sahel-WEB.pdf

Conflict and instability in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has been fuelled by climate change, rapid population growth, widespread poverty and unemployment, weak governance, corruption and human rights violations.4Taylor, Paul. “Crossing the wilderness: Europe and the Sahel” Friends of Europe. Spring 2021. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. https://www.friendsofeurope.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2021_PSD_PUB_Sahel-WEB.pdf The desertification of the Sahel – resulting from rising temperatures, increased exposure to drought and declining water availability – has led to conflict over land and resources between ethnic groups.5Taylor, Paul. “Crossing the wilderness: Europe and the Sahel” Friends of Europe. Spring 2021. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. https://www.friendsofeurope.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2021_PSD_PUB_Sahel-WEB.pdf These tensions have been exacerbated by human rights violations by security forces and armed self-defence groups, often pushing marginalised populations towards jihadist organisations that can provide protection.6Strazzari, Francesco and Luca Raineri “Crisis to watch 2020: The Sahel” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 26 Dec. 2019. Accessed 31. Jan. 2022 https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/crisis-watch-2020-sahel-24705

The crisis in the Central Sahel began with the Tuareg rebellion in Mali in 2012.7A significant factor in the Tuareg rebellion in Mali was the return of fighters and arms from Libya after Gaddafi’s overthrow in Libya. For more information see, “The Central Sahel: A Perfect Sandstorm” International Crisis Group. Africa Report No 227 (2015). https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/niger/central-sahel-perfect-sandstorm Tuareg and Islamist groups conquered territory in Northern Mali, before being pushed out by French forces in 2013.8For more information on the history of Tuareg rebellion in Mali, see Guichaoua, Yvan and Nicolas Desgrais. “Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project: Mali Case Study” UK Government Stabilisation Unit. February 2018. The Tuareg groups signed a peace agreement with the Malian government in 2015, though it was never fully implemented.9Guichaoua, Yvan and Nicolas Desgrais. “Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project: Mali Case Study” UK Government Stabilisation Unit. February 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/766036/Mali_case_study.pdf; “Mali’s Tuareg rebels sign peace deal” BBC News. 20 June 2015. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-33213931; Pellerin, Mathieu. “Mali’s Algiers Peace Agreement, Five Years On: An Uneasy Calm” International Crisis Group. 24 June 2020. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/laccord-dalger-cinq-ans-apres-un-calme-precaire-dont-il-ne-faut-pas-se-satisfaire However, Islamist groups, including Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Ansar Dine, remained active in Mali and violence has since spread to the neighbouring states. In Burkina Faso, President Compaoré’s deposition in 2014 led to the erosion of existing conflict regulation and monitoring mechanisms and the dissolution of the presidential security regiment, an elite regiment that played a crucial role in intelligence and whose role has not been taken on by other national forces.10Guichaoua, Yvan and Nicolas Desgrais. “Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project: Mali Case Study” UK Government Stabilisation Unit. February 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/766036/Mali_case_study.pdf; “Mali’s Tuareg rebels sign peace deal” BBC News. 20 June 2015. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-33213931; Pellerin, Mathieu. “Mali’s Algiers Peace Agreement, Five Years On: An Uneasy Calm” International Crisis Group. 24 June 2020. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/laccord-dalger-cinq-ans-apres-un-calme-precaire-dont-il-ne-faut-pas-se-satisfaire Militant groups operating in Mali were able to build upon local grievances and ineffective military control to gain support in Burkina Faso. Similarly, militant groups crossed over into Niger, taking advantage of porous borders, limited government reach, and entrenched poverty to gain support.11“The Central Sahel: A Perfect Sandstorm” International Crisis Group. Africa Report No 227 (2015). https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/niger/central-sahel-perfect-sandstorm By 2021, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger were all in the top ten countries most affected by terrorism.12Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism, Sydney, March 2022. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/resources (accessed 10 March 2022).

The terrorist threat has continued to evolve. Currently, the al-Qaeda aligned Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State aligned Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) pose the greatest threat. These groups operate throughout Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, have established governance structures, and provide justice and security to communities under their protection.13Boeke, Sergei. “Pathways out of the Quagmire? Perspectives for al-Qaeda in the Sahel” International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague. August 2021. https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2021/08/Counter-Terrorism-Perspectives-for-al-Qaeda-in-the-Sahel-might-work-better.pdf In Mali, the government only exerts its authority within large cities in Central Mali, with much of the rural area effectively controlled by JNIM.14Boeke, Sergei. “Pathways out of the Quagmire? Perspectives for al-Qaeda in the Sahel” International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague. August 2021. https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2021/08/Counter-Terrorism-Perspectives-for-al-Qaeda-in-the-Sahel-might-work-better.pdf

However, militant groups are not entirely to blame for the violence. The security forces of all three countries have committed mass human rights violations and employed communal punishment whilst fighting the jihadist groups, as have the ethnic militias that these governments have used as proxy forces. In 2020, the security forces in Mali and Burkina Faso killed more civilians than the militant jihadist groups, and the Nigerian armed forces were accused of grave abuses against civilians.15“Central Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger)” Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. 01 Dec. 2021. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022.; Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf In 2020, the Human Rights Watch Director for the Sahel wrote that “it is vengeance over extrajudicial executions and other abuses by soldiers and pro-government militias that – more than anything else – is driving recruits into the Islamist ranks.”16Dufka, Corinne. “Sahel: Atrocities by the security forces are fuelling recruitment by armed Islamists” Human Rights Watch. 01 July 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/07/01/sahel-atrocities-security-forces-are-fueling-recruitment-armed-islamists Indeed, violence between jihadists and self-defence militias has fractured around ethnic fault lines, with reprisal attacks often leading to a spiral of violence against civilians of opposing ethnic groups.17Strazzari, Francesco and Luca Raineri “Crisis to watch 2020: The Sahel” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 26 Dec. 2019. Accessed 31. Jan. 2022 https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/crisis-watch-2020-sahel-24705

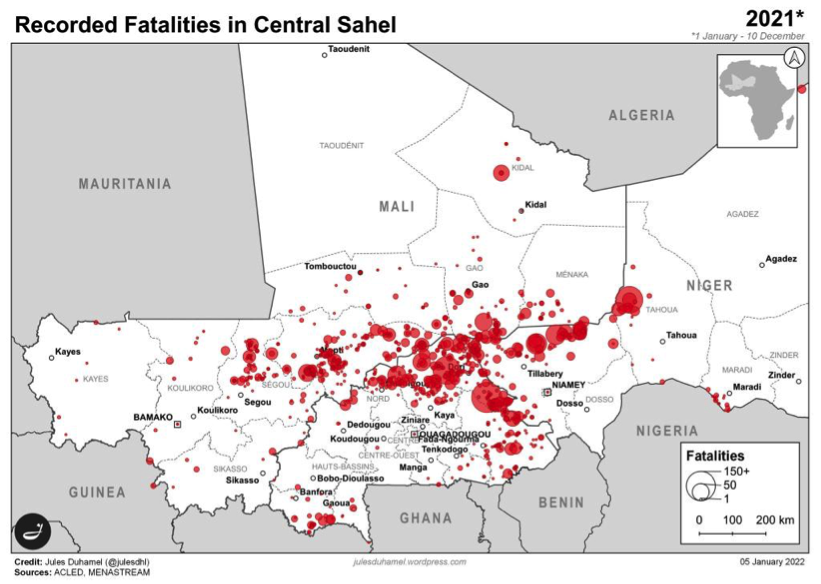

Although most terrorist activity occurs along state borders where government control is weakest (see Map 1), the impact of terrorist violence has been felt across all three countries. In Mali and Burkina Faso, dissatisfaction with the security situation led to coups, with military leaders taking power.18Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf There was also an attempted coup in Niger in 2021. The Institute for Economics and Peace stated that the political instability following the coups and the internal political conflict in Niger were likely to provide jihadi groups with greater opportunities to exploit dissatisfaction with the government and lead security forces to be overstretched in their attempt to balance counterterrorism with internal peacekeeping.19Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism, Sydney, March 2022. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/resources (accessed March 2022).

The impact of political violence and insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has already resulted in thousands of deaths, millions of people displaced, and two democratically elected leaders being overthrown.20President Keita of Mali was overthrown in August 2020 and President Kaboré of Burkina Faso was overthrown in January 2022. For more information see “Mali coup leaders promise elections after Keita overthrow” Al Jazeera. 20 Aug. 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/8/20/mali-coup-leaders-promise-elections-after-keita-overthrow; Ochieng, Beverly. “Burkina Faso coup: Why soldiers have overthrown President Kaboré” BBC News. 25 Jan. 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-60112043 However, there is potential for the situation to worsen. Continued insecurity may lead to future coups or give the transition governments an excuse to postpone the transition to democracy. Already, the military government in Mali has attempted to postpone elections until December 2025.21ECOWAS Commission, “4th EXTRAORDINARY SUMMIT OF THE ECOWAS AUTHORITY OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT ON THE POLITICAL SITUATION IN MALI” Press Release. 9 Jan. 2022, 3. https://www.ecowas.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Final-Communique-on-Summit-on-Mali-Eng-080122.pdf Accessed 10 Jan. 2022 Military governments are unlikely to prioritise holding security forces accountable for human rights violations, even though these are fuelling jihadist recruitment. Government failure to prevent security force violations is likely to escalate the conflict.

Impact on the Surrounding Countries

As with all conflicts, political violence and instability in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has spilled over national borders, impacting the surrounding countries. The neighbouring countries of Chad, Cameroon, Guinea, Mauritania, and Nigeria have all been classified as “hotspots” by the Institute for Economics and Peace, meaning they have low levels of resilience and high or extremely high catastrophic threat levels.22Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism, Sydney, March 2022. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/resources (accessed March 2022). It is thus possible that surrounding countries may be particularly vulnerable to political instability if terrorist groups spill over borders.

Jihadist groups have already been expanding their areas of influence across borders. Suspected JNIM militants have recently carried out attacks in Togo, Benin, and Côte d’Ivoire, with Côte d’Ivoire experiencing at least 12 jihadist attacks in 2021.23Weiss, Caleb. “Jihadist attacks flow into littoral West Africa” FDD’s Long War Journal. 03 Dec. 2021. https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2021/12/jihadist-attacks-flow-into-littoral-west-africa.php Caleb Weiss of the FDD’s Long War Journal has recently expressed his concern that the rise of IED attacks by JNIM in Côte d’Ivoire is “disturbingly similar to the situations in both Burkina Faso and Niger wherein a slow trickle of initial IED’s eventually gave way to larger and more frequent attacks.”24Weiss, Caleb. “Analysis: Ivory Coast witnesses surge in jihadist activity” FDD’s Long War Journal. 16 June 2021. https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2021/06/analysis-ivory-coast-witnesses-surge-in-jihadist-activity.php Additionally, Northern Benin, which has recently been targeted by JNIM, has the same farmer-herder tensions and problems over land ownership as Niger and Burkina Faso, fuelling concern that this may be a futile recruitment ground for jihadist groups.

Infiltrating the coastal states would allow jihadist groups to create new supply lines for food and equipment and to unlock new sources of income, such as banditry, thus providing vital advantages for armed groups.25Durmaz, Mucahid. “Sahel violence threatens West African coastal states” Al Jazeera. 12 Jan. 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/12/sahel-violence-threatens-west-african-coastal-states

Impact to Europe

This section explores five ways in which political violence and insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger threatens Europe. There is significant concern that the success of jihadist groups in the Central Sahel may inspire terrorist attacks in the West – as was seen in France with the 2015 and 2016 Islamist terrorist attacks in Paris and Nice, incidents inspired by the Islamic State’s establishment of a caliphate in Iraq and Syria. 26Buhari, Muhammadu. “Muhummadu Buhari: Africa needs more than US military aid to defeat terror”. Financial Times. 15 Aug 2021. Accessed 27 Jan. 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/5e50eed6-1ca6-4a28-8341-52157b2f946e; Shurkin, Michael. “Abandoning West Africa Carries Risks for U.S” RAND Corporation. 3 Jan. 2020. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022. https://www.rand.org/blog/2020/01/abandoning-west-africa-carries-risks-for-us.html The threat of international terrorist attacks is particularly concerning for France, which has a history of significant Islamist attacks and has been identified by JNIM as its primary enemy.27Newlee, Danika. “Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM)” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 2018. Accessed 01 Feb. 2022. https://www.csis.org/programs/past-projects/transnational-threats-project/terrorism-backgrounders/jamaat-nasr-al-islam The concern is likely amplified by the salience of Political Islam in French politics and the 2022 Presidential elections, in which President Macron faced a significant challenge from the far right. France is also concerned about the possibility of terrorist attacks on the French-owned uranium mines in Niger, which supply three quarters of France’s energy.28Davatti, Daria and Anca-Elena Ursu. “Why Securitising the Sahel Will Not Stop Migration” FMU Policy Brief No 02/2018. 10 Jan. 2018. Accessed 01 Feb. 2022. https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2018-01/PB_Why_securitising_Sahel_won’t_stop_migration.pdf; Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf

Furthermore, jihadist groups in the Central Sahel are also involved in organised crime. Due to the proximity of the Central Sahel to Europe and the well-established smuggling routes through North Africa, European countries are vulnerable to the spill over of prohibited goods and individuals from the Central Sahel into Europe.29Stambøl, Eva Magdelena. “The EU’s fight against transnational crime in the Sahel” Institute for European Studies. Feb. 2019. Accessed 04 Feb. 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eva-Stambol-2/publication/331477860_The_EU’s_fight_against_transnational_crime_in_the_Sahel/links/5c7bad19a6fdcc4715aa33c6/The-EUs-fight-against-transnational-crime-in-the-Sahel.pdf The Africa Organised Crime Index 2021 found that human trafficking, cocaine smuggling, cannabis smuggling, arms trafficking, and the proliferation of synthetic drugs are all rife in West Africa.30“Africa Organised Crime Index 2021” ENACT. 2021. Accessed 04 Feb. 2022. https://ocindex.enactafrica.org/assets/downloads/enact_report_2021.pdf Additionally, unprecedented drug seizures between 2019 and 2021 confirmed the resurgence of the international cocaine trade in the region, with much of the product being supplied to West and Central Europe.31“Organized Crime Perpetuating Instability, Violence, Poverty across West Africa, Sahel, Executive Director Tells Security Council” United Nations Security Council Meeting 8944. Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. 10 Jan. 2022. Accessed 04 Feb. 2022. https://www.un.org/press/en/2022/sc14761.doc.htm; Strazzari, Francesco and Luca Raineri “Crisis to watch 2020: The Sahel” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 26 Dec. 2019. Accessed 31. Jan. 2022 https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/crisis-watch-2020-sahel-24705 Armed groups have also repeatedly engaged in kidnapping for ransom, directly targeting European citizens. In October 2020, JNIM reportedly received €10 million and the release of over 200 fighters in return for the release of French humanitarian worker Sophie Pétronin and Malian opposition politician Soumaîla Cissé.32Thompson, Jared. “Examining Extremism: Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin”. Center for Strategic and International Studies. 15 July 2021. Web. 26 Jan. 2022. https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism/examining-extremism-jamaat-nasr-al-islam-wal-muslimin The Executive Director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime recently stated that the value of illicit flows in the region exceeds the national budgets of some transit countries. Indeed, criminal financial flows in the region further insecurity, heighten weak governance, fuel corruption, and could undermine the transition from war to peace.33Micallef, Mark, Raouf Farrah, Alexandre Bish and Victor Tanner. “After the Storm: Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. 2019. Accessed 04 Feb. 2022. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/After_the_storm_GI-TOC.pdf

European countries are very concerned about the possibility of increased migration and refugee flows that could follow increasing political violence and insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. The EU has already spent billions of euros to stop the small amount of irregular migration from Africa to Europe, and Germany increased troop contributions to the Central Sahel following the 2015 refugee crisis.34Brachet, Julien. “The Sahel, Europe’s “Frontier Zone” for African Migrants” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 03 March 2021. Accessed 02 Feb. 2022. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/sahel-europes-frontier-zone-african-migrants-29307; Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf The 2015 migrant crisis had a corrosive effect on liberal politics and encouraged populist reactions such as Brexit and the growth of far right parties, such as the National Rally and the Alternative for Germany.35Shurkin, Michael and Aneliese Bernard. “Ten Things the United States Should Do to Combat Terrorism in the Sahel” War on the Rocks. 30 Aug. 2021. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/ten-things-the-united-states-should-do-to-combat-terrorism-in-the-sahel/ Europe’s far right parties are xenophobic and share a dislike of American global leadership and a fondness for Russia, thus straining the trans-Atlantic relationship.36Shurkin, Michael and Aneliese Bernard. “Ten Things the United States Should Do to Combat Terrorism in the Sahel” War on the Rocks. 30 Aug. 2021. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/ten-things-the-united-states-should-do-to-combat-terrorism-in-the-sahel/ Thus, European countries are very concerned that the possibility of another refugee crisis would further erode liberal politics. However, EU concern has led to policies that contributed to the deterioration of the security situation, by taking away livelihoods and allowing criminal entrepreneurs, likely linked to armed groups, to replace local actors.37“Migration Trends From, To and Within the Niger” International Organization for Migration. 2020. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iom-niger-four-year-report.pdf; Davatti, Daria and Anca-Elena Ursu. “Why Securitising the Sahel Will Not Stop Migration” FMU Policy Brief No 02/2018. 10 Jan. 2018. Accessed 01 Feb. 2022. https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2018-01/PB_Why_securitising_Sahel_won’t_stop_migration.pdf; Yayboke, Erol and Rakan Abonaaj. “Peril in the Desert: Irregular Migration through the Sahel” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 21 Oct. 2020. Accessed 02 Feb. 2022. https://www.csis.org/analysis/peril-desert-irregular-migration-through-sahel This has not prevented illegal migration but has made it more dangerous and expensive.38Yayboke, Erol and Rakan Abonaaj. “Peril in the Desert: Irregular Migration through the Sahel” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 21 Oct. 2020. Accessed 02 Feb. 2022. https://www.csis.org/analysis/peril-desert-irregular-migration-through-sahel

A fourth concern for European countries is the possibility of great power competition. China has provided 45.5 million USD to the security and counterterrorism operations of the G5 Sahel joint force, indicating a desire for greater influence in the region. Additionally, between 2015 and 2018, Russia signed 20 bilateral military cooperation agreements with African countries, including Niger and Burkina Faso.39Hedenskog, Jakob. “Russia is Stepping Up its Military Cooperation in Africa” Totalförsvarets forskningsinstitut. December 2018. Accessed 05 Feb. 2022. https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI%20MEMO%206604 Protestors supporting the military juntas in Mali and Burkina Faso have also been waving Russian flags and calling for greater cooperation with Russia, whilst calling for the removal of French troops.40“Mali: Protesters call for French troops to leave, some call for greater Russia cooperation” Africa News. 26 June 2021. Accessed 05 Feb. 2022. https://www.africanews.com/2021/06/26/mali-protesters-call-for-french-troops-to-leave-some-call-for-greater-russia-cooperation//; Walsh, Declan. “After Coup in Burkina Faso, Protestors Turn to Russia for Help”. The New York Times. 25 Jan. 2022. Accessed 27 Jan. 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/25/world/africa/burkina-faso-coup-russians.html?campaign_id=51&emc=edit_mbe_20220126&instance_id=51284&nl=morning-briefing%3A-europe-edition®i_id=84796152&segment_id=80734&te=1&user_id=3c6a9dcaec9de5cae1ff8a37abad2e30 Protestors were inspired by Russia’s intervention in the Central African Republic (CAR), where mercenaries from the Wagner group repelled an attack on the capital by insurgents in January 2021, ended a rebel blockade on the CAR’s supply channel from Cameroon, and retook most rebel strongholds after twenty years of insurgency.41Walsh, Declan. “After Coup in Burkina Faso, Protestors Turn to Russia for Help”. The New York Times. 25 Jan. 2022. Accessed 27 Jan. 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/25/world/africa/burkina-faso-coup-russians.html?campaign_id=51&emc=edit_mbe_20220126&instance_id=51284&nl=morning-briefing%3A-europe-edition®i_id=84796152&segment_id=80734&te=1&user_id=3c6a9dcaec9de5cae1ff8a37abad2e30; Bax, Pauline. “Russia’s Influence in the Central African Republic” International Crisis Group. 03 Dec. 2021. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/central-african-republic/russias-influence-central-african-republic Tensions between Mali and European powers escalated after the deployment of Russian Wagner mercenaries; Denmark and Sweden withdrew their troops from the Takuba task force in January 2022 and the EU imposed sanctions.42Faulkner, Christopher Michael. “Rising instability in Mali raises fears about role of private Russian military group” The Conversation. 10 Jan. 2022. Accessed 05 Feb. 2022. https://theconversation.com/rising-instability-in-mali-raises-fears-about-role-of-private-russian-military-group-174634; “Sweden to withdraw from French-led special forces mission Takuba in Mali” France 24. 14 Jan. 2022. Accessed 02 Feb 2022. https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20220114-sweden-to-withdraw-from-french-led-special-forces-mission-takuba-in-mali; “Denmark to start pulling troops out of Mali after junta’s demand” France24. 27 Jan. 2022. Accessed 03 Feb. 2022. https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20220127-denmark-to-start-pulling-troops-out-of-mali-after-junta-s-request

Finally, European countries are also concerned with ‘saving face’ with regards to their presence in the region. French operations in the Central Sahel have been dubbed “France’s Forever War” and compared to the US intervention in Afghanistan; after nine years of operations in Mali, the situation is worse than when France first intervened in 2013.43Maclean, Ruth. “Crisis in the Sahel Becoming France’s Forever War” New York Times. 29 March 2020. Accessed 03 April 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/29/world/africa/france-sahel-west-africa-.html Additionally, the French and EU presence has become increasingly unpopular. In 2021 and 2022, Malian and Burkinabe demonstrators protested French intervention in the region.44“Mali: Protesters call for French troops to leave, some call for greater Russia cooperation” Africa News. 26 June 2021. Accessed 05 Feb. 2022. https://www.africanews.com/2021/06/26/mali-protesters-call-for-french-troops-to-leave-some-call-for-greater-russia-cooperation//; Walsh, Declan. “After Coup in Burkina Faso, Protestors Turn to Russia for Help”. The New York Times. 25 Jan. 2022. Accessed 27 Jan. 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/25/world/africa/burkina-faso-coup-russians.html?campaign_id=51&emc=edit_mbe_20220126&instance_id=51284&nl=morning-briefing%3A-europe-edition®i_id=84796152&segment_id=80734&te=1&user_id=3c6a9dcaec9de5cae1ff8a37abad2e30 The French ambassador was expelled from Mali in February 2022 and President Macron announced the removal of French forces from Mali in February 2022.45“French ambassador expelled from Mali” BBC News. 31 Jan. 2022. Accessed 03 April 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-60202343; “Why are French troops leaving Mali, and what will it mean for the region?” BBC News. 17 Feb. 2022. Accessed 03 April 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-60419799 However, Katherine Pye of the Centre for European Reform notes how success in the Sahel has become important for Europe’s credibility as a crisis manager as “the EU must now prove it is capable of solving complex problems in its own backyard.”46Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf

The Current Approach

The current approach to improving the security situation in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has primarily focused on counterterrorism techniques, such as leadership decapitation. While this approach has had some limited success – including killing the EMIR of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Abdelmalek Droukdel, and the leader of Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi – this approach has not been effective in restoring security.47Gardner, Frank. “Al-Qaeda chief in north Africa Abdelmalek Droukdel killed – France” BBC News. 05 June 2020. Accessed 03 April 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-52943692; Wheeldon, Tom. “Sahrawi: The top Sahel jihadist killed in French ‘opportunistic hit’” France24. 16 Sep. 2021. Accessed 03 April 2022. https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210916-the-assassinated-abou-walid-al-sahrawi-france-s-major-enemy-in-the-sahel Many tactical victories have been undermined by security force violations that have pushed populations into the arms of the jihadists. Indeed, a Chatham House report states that “military action against armed groups will fail as long as impunity prevails and local armies can kill civilians and topple governments without consequence.”48Pérouse de Montclos, Marc-Antoine. “Rethinking the response to jihadist groups across the Sahel” Chatham House Africa Programme. March 2021 Additionally, there are so many international forces acting in the Central Sahel that it has been referred to as a “Security Jam,” with forces deployed through the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the French Operation Barkhane, the EU Training Mission in Mali, the EU Civilian and Law Enforcement Capacity Building Missions in Mali and Niger, the EU Task Force Takuba, and the G5 Sahel Force. 49Cooke, Jennifer G., Boris Toucas and Katrin Heger “Understanding the G5 Sahel Joint Force: Fighting Terror, Building Regional Security” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 15 Nov. 2017. Accessed 27 Jan. 2022. https://www.csis.org/analysis/understanding-g5-sahel-joint-force-fighting-terror-building-regional-security; “MINUSMA FACT SHEET” United Nations Peacekeeping. Accessed 04 Feb. 2022. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusma; Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf However, each operation has varying objectives and capabilities.

Sahelian governments, Western governments, think tanks, NGOs and citizens’ movements, journalists, and academics all identify good governance as the solution to insecurity in the Sahel.50Thurston, Alex. “The Hollowness of “Governance Talk” in and about the Sahel” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 13 April 2021. Accessed 03 April 2022. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/hollowness-governance-talk-and-about-sahel-30026 However, there is no funding for long-term projects in the Central Sahel. While France has 89 civil servants per 1,000 inhabitants, Burkina Faso has only eight, Mali has six, and Niger only three.51Thurston, Alex. “The Hollowness of “Governance Talk” in and about the Sahel” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 13 April 2021. Accessed 03 April 2022. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/hollowness-governance-talk-and-about-sahel-30026 How France has allocated spending also demonstrates their priorities; France has spent approximately 900 million euros on Operation Barkhane, but only 85 million on bilateral development aid to Mali.52Boeke, Sergei. “Pathways out of the Quagmire? Perspectives for al-Qaeda in the Sahel” International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague. August 2021. https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2021/08/Counter-Terrorism-Perspectives-for-al-Qaeda-in-the-Sahel-might-work-better.pdf Additionally, attempts by European countries and their allies to reduce violence have been undermined by their support for governments that are feared and mistrusted by many of their citizens.53Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf European attempts to restore the state presence are not desirable to the many citizens who perceive the state authorities as predatory and corrupt.54Pye, Katherine. “The Sahel: Europe’s forever war?” Centre for European Reform. March 2021. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_sahel_31.3.21.pdf; Schmauder, Anna, Guillaume Soto-Mayor and Delina Goxho. “Strategic Missteps: Learning From a Failed US Sahel Strategy” Italian Institute for International Political Studies. 05 Nov. 2020. Accessed 01 Feb. 2022. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/strategic-missteps-learning-failed-eu-sahel-strategy-28130 When European allies do not condemn human rights abuses by the security forces they work with and have trained, their credibility is damaged and their effectiveness is limited.

Recommendations

- The Malian, Nigerian, and Burkinabe governments, along with the EU and other allies, should move from a short-term counterterrorism focus to a long-term commitment to development.

- The governments should give greater attention to service provision, notably healthcare and education, even in areas where security forces are not deployed.55“A Course Correction for the Sahel Stabilisation Strategy” International Crisis Group. 1 Feb. 2021. Accessed 05 Feb. 2022. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/299-course-correction-sahel-stabilisation-strategy Jihadist groups are often accepted by communities because they are able to provide services, such as security and justice, where the government has been unable to.56Boeke, Sergei. “Pathways out of the Quagmire? Perspectives for al-Qaeda in the Sahel” International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague. August 2021. https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2021/08/Counter-Terrorism-Perspectives-for-al-Qaeda-in-the-Sahel-might-work-better.pdf Thus, a focus on providing these services may deter communities from allying with jihadist groups.

- The EU and its allies should be willing to sanction governments that are complicit in human rights abuses, as human rights abuses facilitate jihadist recruitment.57Ioannides, Isabelle. “Peace and security in 2020: Evaluating the EU approach to tackling the Sahel conflicts” European Parliamentary Research Service. Sep. 2020. Accessed 05 Feb. 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/654173/EPRS_STU(2020)654173_EN.pdf

- Sahelian governments and their allies should also be open to negotiations. Already, the Sahelian states open attitude to bottom-up negotiations has significantly reduced violence in several districts in Central Mali and Burkina Faso.58Boeke, Sergei. “Pathways out of the Quagmire? Perspectives for al-Qaeda in the Sahel” International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague. August 2021. https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2021/08/Counter-Terrorism-Perspectives-for-al-Qaeda-in-the-Sahel-might-work-better.pdf Both the Malian government and JNIM have expressed interest in opening dialogues, though the French government has refused to be open to the possibility.59“Mali: Enabling Dialogue with the Jihadist Coalition JNIM” International Crisis Group Report No 306. 10 Dec. 2021. Web. Accessed 24 Jan. 2022 https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/306-mali-enabling-dialogue-jihadist-coalition-jnim Although negotiations should be careful not to allow jihadists to cement their control over local communities, counterterrorism operations alone are unlikely to defeat jihadi groups.60Boeke, Sergei. “Pathways out of the Quagmire? Perspectives for al-Qaeda in the Sahel” International Centre for Counter Terrorism – The Hague. August 2021. https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2021/08/Counter-Terrorism-Perspectives-for-al-Qaeda-in-the-Sahel-might-work-better.pdf

Based on your interests, you may also wish to read:

- Imperial Reckoning: an exceptional investigation into the violence and brutality which characterized the end of empire in Kenya

- Prosperity & Poverty in Post-Independent Africa Debated

- An Emerging Landscape of Terror in Mozambique: Implications for the Southern African Development Community

- ECOWAS’ Response to Coups in West Africa, 2020-2021